Two years ago, I was half-watching the Disney Channel with my nephew and niece when a commercial startled me—not because a fleeting tween sensation had finally done something funny, but because I couldn’t believe they were airing a two-minute promo for poetry. Backstage at a children’s poetry slam, Caroline Kennedy was chatting about her new Disney-backed anthology, Poems to Learn by Heart, without naming a single poem in the book. Naturally, I wondered: What sort of anthology do we get from a network that exalts dancing and singing above all other human endeavors?

Two years ago, I was half-watching the Disney Channel with my nephew and niece when a commercial startled me—not because a fleeting tween sensation had finally done something funny, but because I couldn’t believe they were airing a two-minute promo for poetry. Backstage at a children’s poetry slam, Caroline Kennedy was chatting about her new Disney-backed anthology, Poems to Learn by Heart, without naming a single poem in the book. Naturally, I wondered: What sort of anthology do we get from a network that exalts dancing and singing above all other human endeavors?

As it turns out, a pretty conservative one. Poems to Learn by Heart isn’t the slam-tastic book the commercial makes it out to be; instead, it’s full of traditional, anthology-friendly names: Shakespeare, Byron, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Stephen Crane, Wallace Stevens, Langston Hughes, Rita Dove, Richard Wilbur—around a hundred poets in all. Adults who want poetry to be “edgy” will find the selection cautious—the wildest poet here is Amiri Baraka, whose “Ballad of the Morning Streets” won’t shock grandma—but Kennedy has less seasoned readers in mind. To her credit, she knows that while most English majors have read poems like “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks, most American children (and their parents) have not. She also gets that this book’s 183 pages contain more poetry than most kids will encounter in twelve years of school, so it’s a rare chance to show them what the English language has to offer, from Lewis Carroll to Nikki Giovanni.

Even though Kennedy arranges her selections by subject (“the self,” “family,” “friendship and love,” “faeries, ogres, witches,” “nonsense poems,” “school,” “sports and games,” “war,” and “nature”), Poems to Learn by Heart doesn’t feel guided by a clear editorial point of view. Of course, that’s an adult concern; young readers who don’t yet know their own tastes may enjoy discovering Ovid, Countee Cullen, and Robert Louis Stevenson alongside a Navajo prayer, the Gettysburg Address, the St. Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V, selections from the First Letter of Paul to the Corinthians, and Martin Niemöller’s “First they came for the Socialists” speech. I appreciate breadth, and even the inclusion of lyrical prose, but is it here to foster inclusiveness, or to deflect criticism? One could easily use the table of contents to reconstruct the minutes of Disney’s fretful editorial meetings: Something for the religious? Cultural-literacy conservatives? Social-justice liberals? Native Americans? Check, check, check, and check.

Despite these thoughtful, wide-ranging selections, this book doesn’t always fulfill the promise of its title. Kennedy may be gung-ho for memorization, but I didn’t always see the mnemonic value of her selections: Is “Peace” the one Gerard Manley Hopkins poem to remember? Why learn Shakespeare’s sonnet 94 instead of one of the others? Kennedy asked a six-member poetry slam team at a Bronx high school to help pick these poems, and she devoted four pages to their own passionate free-verse poem about racism, consumerism, child abuse, and mass media. While I hope the publication credit gave their lives a hearty boost, I do wonder, perhaps heartlessly, if their work belongs here. For whom other than the teens who wrote and performed it is it a “poem to learn by heart”?

I was also baffled by the selections in a final “extra credit” section: “Young Lochinvar” by Walter Scott, “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Longfellow, “Kubla Khan” by Coleridge, Robert Service’s crowd-pleasing “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” and the first 18 lines of the General Prologue of The Canterbury Tales. “Mostly they are old chestnuts that have fallen out of favor,” the scion of a privileged political dynasty warns us, lest she come off as a square, “but the feats of memory required to master them will impress even the most modern audiences.” Why can’t the editor of a poetry anthology write as if she actually believes that old things have value beyond their potential for self-exploration and showing off? (And who the heck drops Chaucer on kids without a pronunciation guide?)

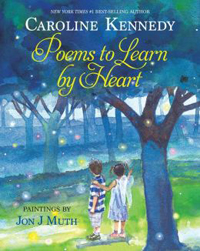

That final section highlights this book’s major flaw: a lack of wild, wham-bang narrative. Jon J. Muth’s illustrations are beautiful, but his cover captures the overall mood: gentle, contemplative, dreamy. That’s fine for some kids, but what about action for the more rambunctious? It’s not my style to call for a book to be less intellectual (or for things Disney to be less introspective), but cripes, what about a good, gory chunk of Beowulf or Homer, or an Asian or African epic? Where are the pirates, cavemen, and ghouls of Robert E. Howard? Except in passing in its introduction, Poems to Learn by Heart forgets to teach kids that some of humanity’s best stories are told in verse—and that people proudly carry them around in their heads.

I hate to be hard on this book. For many kids, it will be their only introduction to poetry, and some, I hope, will adore it. Decades from now, if those readers fondly remember this book as adults, the Disney Channel will deserve praise for marshaling its legions of wolf-mounted marketing goblins in support of something more sophisticated than terrible sitcoms—nothing less than Octavio Paz, Seamus Heaney, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Elizabeth Bishop, and Ovid. Only then will I know if Poems to Learn by Heart has served children well or if it’s the century’s first great, unread gift book, a smart, well-intentioned effort to elevate young readers that’s (maybe) too pensive, too mousey, too nice.

About 15 years ago at a school book fair, I noticed Committed to Memory: 100 Best Poems to Memorize, an anthology assembled by John Hollander. It has no illustrations. Hollander arranges the poems as Sonnets, Songs (for example, “The Song of Wandering Angus”) , Counsels (“Brahma”, “If”), Tales (“Casey at the Bat”, “Adlestrop”), and Meditations (“Spring and Fall”, “Mnemosyne”). One could argue endlessly over what to fit into the hundred, but nearly all of the selections strike me at at least defensible. And it is about the poetry, not ticking off boxes. It appears to be out of print, but not hard to find.

As for the extra credit, the problem that I find with Scott’s poetry is that it tends to get overlaid in memory by Lewis Carroll’s parodies. (The same is true in part for Longfellow: I can give you ten lines of “Hiawatha’s Photographing” for any one of “Hiawatha”). Yet I think I once knew “Lochinvar”. My stepmother memorized “Paul Revere” in grade school, on her own initiative, for the requirement was only a stanza, and 70-odd years later can still give you most of it.

I think that if I had to reach for the battle and adventure, I’d fall back on “Horatius at the Bridge” or “Spanish Waters”, though I now remember little of either

LikeLike

George, I think you’ve recommended Committed to Memory to me before, but I’m glad you’ve mentioned it again so I can keep an eye out for it when I next make the rounds of used bookstores. (I always check the “H” section for Hollander’s other books, but it occurs to me I need to be checking the anthology shelves, too.)

I had to memorize a Russian poem for an oral exam 25 years ago, and I can still recite it with gusto. I’m learning German now, and committing songs and poems to memory has proven to be one of the better ways to make vocabulary stick to a brain that’s no longer young…

LikeLike

I’m very fond of this collection:

Ya vas lyubil; lyubov yeshaw, buyt mozhet,

f’dushay moay ugasla ne sovsem …

http://lyricstranslate.com/en/ya-vas-ljubil-ya-vas-lyubil-i-loved-you-once.html

My memory’s holding up pretty well too. Everybody ought to have one Russian poem …

LikeLike

Interesting! Thanks for pointing that one out to me, Withywindle.

The Russian poem I can still recite is Lermontov’s “Sails.” After 25 years, my understanding of the grammar and vocabulary have withered, but the experience probably got me thinking about the sound of poetry rather than the sense. Useful, that.

LikeLike