How did art become irrelevant? Michael J. Lewis’s answer to that question in Commentary magazine made the rounds of social media last week. It’s an exhaustive overview, and a political one, edged with fine anger, a reminder that the arts used to be merely elitist, not ruthlessly hermetic.

How did art become irrelevant? Michael J. Lewis’s answer to that question in Commentary magazine made the rounds of social media last week. It’s an exhaustive overview, and a political one, edged with fine anger, a reminder that the arts used to be merely elitist, not ruthlessly hermetic.

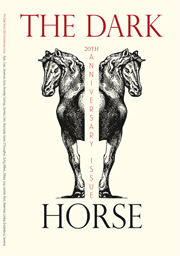

So I was startled to open the latest issue of the literary magazine The Dark Horse and find “Poetry as Enchantment,” an essay by former NEA chairman Dana Gioia that makes many of the same points Lewis makes, but solely about poetry, and with a far more subdued tone. Defending poetry as a universal human art with roots in music, charms, and incantations, Gioia recalls that not long ago, it was ubiquitous and widely enjoyed. I remember that too: my grandfather was a machinist with a grade-school education, but he could rattle off snippets of verse that I now know were the work of Longfellow, Joyce Kilmer, and the (utterly forgotten) Sam Walter Foss.

What happened? Gioia argues that poetry was too well taught. The New Critics imposed reason, objectivity, and coherence on it. “Learning” poetry was reduced to dissection and analysis, then demonstrating your fluency in each new school of critical theory:

For most students, writing a critical paper does not inspire the same lifelong affection for poetry that memorization and recitation foster. When analytical instruction replaces the physicality, subjectivity, and emotionality of performance, most students fail to make a meaningful connection with poetry. So abstracted and intellectualized, poetry becomes disembodied into poetics—a noble subject but never a popular one. As the audience for poetry continues to contract, there will come a tipping point—perhaps it has already arrived—when the majority of adult readers are academic professionals or graduate students training for those professions. What is the future of an art when the majority of its audience must be paid to participate?

No one intended the decimation of poetry’s audience or the alienation of the common reader. Like most environmental messes, those things happened as accidental by-products of an otherwise positive project.

Gioia literally marketed Kool-Aid as an executive at General Foods—who can ever forget his award-winning “fear in a handful of dust” campaign?—so when he became NEA chairman in 2003, he wanted measurable results:

We decided to start with a program that could be executed quickly on a large scale without a huge investment. What we conceived was a national poetry recitation contest for high school students that would begin at class level, and then move on to school, local, state, and national competitions. We successfully tested the idea in Chicago and Washington, D.C., but when the agency tried to expand it, the arts education officials in the 50 states initially refused to adopt it.

The state arts education experts had four major objections to the program. First, they believed that students hated poetry. (Am I wrong to suspect that this assumption suggests that the experts themselves disliked poetry?) Second, they maintained that memorization was repressive and stifled creativity. Some of them added that memorization victimized minority students since standard English was not spoken in their homes. Third, they unanimously felt that competition had no place in the arts. There should be no winners or losers. In arts education, everyone should win. Finally, there was a general feeling among the educators that poetry was too intellectual for the average student. It was not an accessible art.

Just how wrong were those “state arts education experts”? Gioia found that kids raised with hip-hop took to poetry when it became about hearing and reciting rather than reading and analyzing; they loved competing; “problem kids” turned out to be great at it; and immigrant kids have turned out to be around half of all winners each year.

Gioia is too gracious to gloat. About his detractors, he says only this: “The administrators and arts consultants were openly astonished by the program’s popularity.” I wonder why they doubted him: His longtime championing of old-fashioned formalism? His corporate background? His presumed political affiliation? It’s a dreary state of affairs when ignorance is the most charitable explanation.

Someone recently quipped on Facebook that it’s actually a great time to be a poet, because when an art has zero social cachet, the people who do it out of sheer love don’t have to wonder if others are into it for the wrong reasons. That may not be forever true: Gioia’s Poetry Out Loud program has already engaged 2.5 million high-school kids, and books like the Disney Channel poetry anthology are bracing their younger siblings. What if channeling rap fandom into national recitation contests actually entices the corpse of poetry to sprout and bloom some year? Relevance would uproot academia; it wouldn’t be kind; it would set poets slogging through swamps of conflict and commerce, not noticing how many more people had finally learned that they’re meant to talk about what Gioia calls “mysteries that lie beyond paraphrase,” their inheritance as human beings.

This feels like a struggle for control over a community which I do not know and am not part of, and I try to keep out of those. I trust that you are familiar with Neal Stephenson’s model of the Dante writer and the Beowulf writer? http://slashdot.org/story/04/10/20/1518217/neal-stephenson-responds-with-wit-and-humor (that thread is worth reading in general) Thanks for the links to help foreigners get their bearings in this Kulturkampf.

LikeLike

Thanks for this, Sean. I think Stephenson’s Dante/Beowulf model (which was new to me until just now) is a useful generalization, but I’d hate for people to see the creation of art as a matter of either one or the other. (Interestingly, in the U.S., the patronage model helped fund several influential artists and poets at least as recently as the Harlem Renaissance, so it’s not as distant a phenomenon as many might think.)

For my part, I’ve never been a culture warrior; I’d like to see all forms of art and poetry in wider circulation so that these small, closed communities alienate fewer people and come to matter far less than they do.

LikeLike

Indeed, I am sure that there were people reciting bits of Dante in taverns, and that the Beowulf poet would have happily written a poem of praise for a generous ring-giver. But Stephenson is a novelist with a gonzo style, not an academic, so I don’t expect him to make sure that all the details are right before he takes a shiny idea and runs with it.

It is just … some people like to talk about a battle between ‘the literary establishment’ and ‘commercial fiction’ or ‘genre fiction,’ but what I see is a cluster of communities which like what they like, organize awards to give thanks for especially clever examples, and mostly ignore what other communities are doing. If some people in ‘the literary establishment’ turn up their noses at romance novels or mysteries, plenty of mystery fans don’t read ‘literary fiction’ written in the past fifty years. If anyone in academic circles is bothered that I sometimes write about history in venues which sell more than a thousand copies and don’t allow footnotes, I am blissfully innocent of it.

LikeLike

Oh, I don’t think Stephenson quite gets all the details right at all, but his model is still a useful way to start explaining the economics of art to people who’ve never thought about it before.

Okay, I now better understand your point. I agree that those preference-communities often seem less at odds with each other than people with political agendas would have us believe. In any case, as a reader, I like writers who are just as “blissfully innocent” as you are about genre and community boundaries; it’s why I still read blogs.

…and I think what you’re saying also applies to rants about “modern art.” When writers (like the author of that Commentary piece) lament postmodernist performance pieces and art that refers only to itself, they’re not wrong about the severely limited appeal of such work and the social consequences, but the world is still full of more traditionally trained artists doing their thing. The time that guy spent writing that screed could have been used to bring all sorts of hard-working, little-known artists to public attention. (That’s a big part of why I appreciated Gioia’s poetry article: it wasn’t a lament, but the story of his own successful efforts to do something productive.)

LikeLike

Yes, I think that the dichotomy of Dante authors and Beowulf authors is useful as long as one treats it as a metaphor not mathematics, and Neal Stephenson has such fun describing it that its hard to be indifferent to it. (He also spends a few lines warning readers that any way of dividing people into two distinct groups has its dangers). I can’t say what happens among people who control curricula in American highschools, or the contents of book-review sections in American magazines, but it seems to me that that sort of conflict is often hard to understand unless you are part of the community, and coming in as an outsider and telling people how to run things rarely goes well. If some modern art and poetry is a bit baffling to me, there are still plenty of things to see and hear which I do enjoy.

I have been trying to spend less energy criticizing things which I do not like, or people who work on projects which do not seem interesting or urgent to me, and more on talking about things which I do like, and doing those interesting urgent projects myself even if I am not as qualified as some people who could do them. I am really an Epicurean at heart, but sometimes the Stoa has something to teach me too.

I wonder what the late Frederick Pohl would have made of Dana Gioia. About ten years ago he revised “The Space Merchants” with its speech about poets learning to write ad copy.

LikeLike

When it comes to being “not as qualified as some people” who could do “those interesting urgent projects,” I can only say that plenty of people have been more qualified to write nearly everything I’ve ever written, but somehow, they never got around to it, and I did, or I soon will. Follow-through counts for a great deal!

Gioia has been inspired to write about poets’ day jobs, but I don’t know if he’s ever discussed how his former career helped him prosper as a poet. Your comment gives me good reason to dive into his prose again. I like his poetry and I admire his work as an arts advocate; his tenure with the National Endowment for the Arts was just about the only time I wished I’d had a government job. (And God help me, I’ve written more than my share of marketing copy for money…)

LikeLike

This makes me feel a little better about how I’m approaching poetry with my (homeschooled) kids. We just read and note phrases or images that stand out to us, memorize, recite, repeat. We read a different poem every day and you tube has been amazing for finding poems read by the authors themselves, including some very old recordings of interwar poets. I’m not a scholar, I just like poetry. I think if I can raise kids who as adults can say the same thing, I’m declaring a victory.

LikeLike

Thanks for stopping by, Elise!

“I’m not a scholar, I just like poetry.” That’s the mindset that will help keep the arts alive, and if you raise kids who can say the same thing, then it’ll be more than just a personal victory, but a cultural one. By and large, schools, museums, and artists have done a terrible job of cultivating new audiences for poetry and the arts, and the larger culture openly hates the fine arts. Inculcating this appreciation in your kids is (as I think we discussed in person a while back!) literally countercultural.

LikeLike

Elise, I agree. Poetry should be fun, and most poets and songwriters are not academics. And someone who reads a lot is more likely to read something which I enjoy than someone who does not read for pleasure at all because they were taught that what they enjoyed reading was bad.

One poet who I am glad to support, even if she likes less structured forms of poetry and more abstract ways of talking about it than I do, is Suzanne Steele http://www.warpoet.ca/

LikeLike

Did you read William Logan’s piece arguing that poetry has long been a major art with a minor audience? http://www.nytimes.com/…/poetry-who-needs-it.html He starts from that viewpoint and declares that it’s not so bad and why…

Elise’s children are far more likely to have a genuine experience when they read a poem than most. And that’s what it should be, a good experience with magical sound, color, beauty, truth…

I’ve been rather surprised that such a weird long poem as Thaliad continues to find readers–maybe the situation is less grim than I had thought a few years ago. Though certainly the audience is small enough! And certainly there’s a lot more sound play in new songs than a few years back, not just rhyme but pleasure in using the same word repeatedly to mean different things, etc.

LikeLike

I don’t know. Randall Jarrell’s essay, “The Obscurity of the Poet”, was written in the 1950s, when the New Criticism was going strong, but still fairly new; a generation of readers hadn’t been raised with it. Yet he complained of the lack interest in poetry in the English-speaking world, mentioning in passing that it still had a large audience in Latin America. I remember students in sophomore-level survey class, forty years ago, groaning when the professor announced that there would be another week of reading poetry. Now, this was the postwar American lineup of Lowell, Jarrell, Shapiro, Wilbur, maybe reaching to the Beats or at least Alan Ginsburg, and I can get enough of them fairly quickly.

On the other hand, five or six years ago I saw a young acquaintance, a recent high school graduate, on the bus, dressed to the nines and headed for a poetry slam, one that I think she had helped to organize. My impression was that there would be a healthy number of people there It seemed to me that she could have converted the most Philistine of young men to an interest in poetry slams if not poetry. I wished, as soon as I got off the bus, that I had asked her to describe the protocols of poetry slams.

LikeLike

Marly: Thanks for stopping by! I missed that Logan piece when it ran last year, so I appreciate the pointer to it.

George: I think the cultural shift pre-dates your college experience and Jarrell’s essay. I suspect that my grandparents’ generation, consisting of folks born in the first two decades of the twentieth century, were the last ones for whom poetry was central. The slam poetry you’re talking about certainly is poetry, but it strikes me as a narrow sub-genre of a much larger, little-understood art.

LikeLike