Most aspects of medievalism in America don’t baffle me. I understand why we want to lay down European roots through Gothic architecture, I get why the pedigreed chivalry of Charlemagne and King Arthur might appeal to us, and the imaginative pleasures of medieval-ish fantasy are (mostly) self-evident. But Dante? I’ve never grasped what Americans hope to do with him—maybe because the answer turns out to be “everything.”

While Dante helped rally Italian nationalism in the early 19th century, Americans looked to him for different shades of inspiration. Melville saw him as a guide through moral quagmires; Emerson considered him a simple genius; and others longed for his unshakeable certainty in their own supposedly weak-willed and overly tolerant age. Charles Eliot Norton, who promoted the study of Dante at Harvard and established the Dante Society of America, praised the poet for representing “the mediaeval spirit found in the highest and completest expression”—namely, an ahistorical vision of independence, individualism, and curiosity he hoped would prosper in post-Civil War America.

After American Protestants dunked Dante in their own ecstatic rivers, Eliot and Pound dwelt largely on his words, adoring him as a poet who wed precision to faith. More recently, the Big D has thrived in a popular culture beguiled by mysticism and the occult. Oh yes: You can pop “Dante’s Inferno Balls” candy while playing the Dante’s Inferno game for XBox or Playstation (with accompanying action figure). You can imagine the scent of Dante cigars, fondly recall the “Dante’s Inferno” ride at Coney Island, or show off your snazzy Dante earrings. You can also check out how two science-fiction authors Americanized Dante to make his Hell literally escapable.

So is Dante nothing more than a leering cadaver we clothe in our whims? In a blog post about two new Dante books, Cynthia Haven at Stanford suggests that il Poeta has something greater to offer us, a vision as priceless as it is stark:

A more interesting question might be: what does Dante tell us about our world that we do not recognize ourselves? Here’s my take: we live in a time and in a generation that thinks everything is negotiable, and that every psycho-spiritual lock can be jimmied. As W.H. Auden put it, we push away the notion that “the meaning of life [is] something more than a mad camp.” For us, there’s always a second, third, and fourth chance. It’s a strength – but it’s a weakness, too. Maybe that’s why we resist Dante. We don’t realize that some things are for keeps. There’s not always another day. Not all choices can be reversed with every change of heart – and no, our heart isn’t always in the right place. Words unsaid may remain forever unsaid. And perhaps no choice is trivial or innocent: it is the choices that bring us to ourselves, the choices that reveal and work as a fixative for our loves, our priorities, and our direction.

Just before Christmas, I checked out “The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists” at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah. The title was misleading, since the art wasn’t inspired by Dante; the works only echoed his concepts and themes. “The concern here is not with the Divine Comedy or Dante,” explained the curator, “but with something truly universal.” How gloomy, but how unsurprising, that another interpreter of Dante, another artist in search of the timeless, doesn’t discern that they’re one and the same.

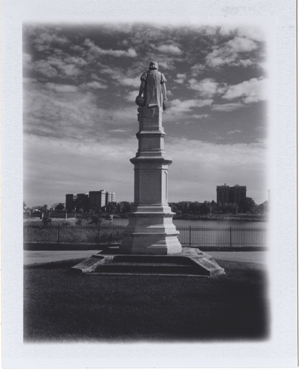

I spent the day before Columbus Day doing research at the Johns Hopkins library—but when I was done, I roamed the city looking for something medieval to photograph. There’s a statue of William “Braveheart” Wallace along the reservoir in Druid Hill Park, but the afternoon light fell far more serendipitously on this Christopher Columbus monument from 1892.

I spent the day before Columbus Day doing research at the Johns Hopkins library—but when I was done, I roamed the city looking for something medieval to photograph. There’s a statue of William “Braveheart” Wallace along the reservoir in Druid Hill Park, but the afternoon light fell far more serendipitously on this Christopher Columbus monument from 1892. No, gnomes aren’t medieval, but they are rooted in 19th-century European medievalism, and there’s certainly a medieval tradition of wee woodland beings making trouble for us humans. Some Anglo-Saxon charms even blame certain types of pain and disease on wicked little “elves.” (Plus, this gnome is made out of felt, the discovery of which is

No, gnomes aren’t medieval, but they are rooted in 19th-century European medievalism, and there’s certainly a medieval tradition of wee woodland beings making trouble for us humans. Some Anglo-Saxon charms even blame certain types of pain and disease on wicked little “elves.” (Plus, this gnome is made out of felt, the discovery of which is

“…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”

“…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”