I’m rarely in sync with the squeaking styrofoam cogs of the news cycle, but sometimes a story turns my head, and I can write about it even after several weeks because it fits a pattern I halfway wish I hadn’t noticed.

I’m rarely in sync with the squeaking styrofoam cogs of the news cycle, but sometimes a story turns my head, and I can write about it even after several weeks because it fits a pattern I halfway wish I hadn’t noticed.

Transport us, O muse of blogging, to England, where at the end of last month, the Manchester Art Gallery removed a painting that apparently troubled almost nobody but museum staff:

It is a painting that shows pubescent, naked nymphs tempting a handsome young man to his doom, but is it an erotic Victorian fantasy too far, and one which, in the current climate, is unsuitable and offensive to modern audiences?

Manchester Art Gallery has asked the question after removing John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs, one of the most recognisable of the pre-Raphaelite paintings, from its walls. Postcards of the painting will be removed from sale in the shop.

The painting was taken down on Friday and replaced with a notice explaining that a temporary space had been left “to prompt conversations about how we display and interpret artworks in Manchester’s public collection.” Members of the public have stuck Post-it notes around the notice giving their reaction.

[. . . ]

[Curator of contemporary art] Gannaway said the removal was not about censorship.

[ . . . ]

Waterhouse is one of the best-known pre-Raphaelites, whose Lady of Shalott is one of Tate Britain’s bestselling postcards, but some of his paintings leave people uncomfortable . . .

We can’t have art making generically identified “people” uncomfortable, now can we?

This story ripened and rotted fast. After seven days of ridicule, the museum put the painting back on the wall and continued to claim that the removal itself was itself an artistic act to accompany a new exhibition. No one explained why that stunt necessitated the disappearance of postcard replicas from the gift shop.

Four days later, I read that concerns about discomfort prompted a major change to the high-school English curriculum in Duluth:

A Minnesota school district is removing To Kill a Mockingbird and Huckleberry Finn from its required reading list because they contain racial slurs.

[ . . . ]

The decision was praised by the local chapter of the NAACP.

Call me crazy, but a town that’s more than 90 percent white is doing all students a disservice by not demonstrating to them that mature, thoughtful readers of any age can discuss fictional depictions of racism without succumbing to emotional breakdowns.

I wish I hadn’t noted so many similar stories in the past year:

- Don’t like a poem on a Berlin college wall from the point of view of a guy who likes to look at flowers and women? Paint over it!

- Receive a single complaint by a gallery employee about paintings inspired by Nat Turner’s slave revolt? Replace them with squares of tape—at the artist’s behest!

- Someone doesn’t like art inspired by someone else’s racial or ethnic experience? Block it from view or destroy it entirely!

- Someone writes a young-adult novel with a crimethinkful narrator? Destroy it before it even comes out!

Ten minutes of searching will net you many more such examples, without even considering professors getting fired for asinine comments, the toppling of statues—which, yes, are also works of art—by latter-day iconoclasts, or the policing of jokes between friends of different races in the music world.

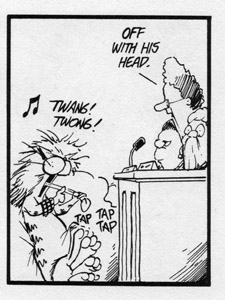

It’s an old story, this business of people telling other people what they can read, see, say, make, or know, but one thing has changed since my teenage years. The perpetrators used to be finger-wagging church ladies. They called on TV networks, libraries, schools, stores, and museums to restrict or ban books, music, and art. They received an inordinate amount of deference and press attention while trying to stoke moral panic about comic books, rock music, role-playing games, newspaper cartoons, radio hosts, shows about liberal priests, Satanic corporate logos, or whatever other ungodly cultural mooncalf shambled past their porch. Artists, writers, and other creative souls replied, sensibly, that people who didn’t want to read or see certain things could and should change the channel or skip the museum and let fellow citizens make their own choices.

It’s an old story, this business of people telling other people what they can read, see, say, make, or know, but one thing has changed since my teenage years. The perpetrators used to be finger-wagging church ladies. They called on TV networks, libraries, schools, stores, and museums to restrict or ban books, music, and art. They received an inordinate amount of deference and press attention while trying to stoke moral panic about comic books, rock music, role-playing games, newspaper cartoons, radio hosts, shows about liberal priests, Satanic corporate logos, or whatever other ungodly cultural mooncalf shambled past their porch. Artists, writers, and other creative souls replied, sensibly, that people who didn’t want to read or see certain things could and should change the channel or skip the museum and let fellow citizens make their own choices.

Back then, threats to wall off artists and writers from the public came from the outside. Now, however, the poles in the art world have flipped. Curators, professors, artists, teachers, readers, and students—the people we once entrusted to protect free expression or expected to defend open access to books, art, and ideas—are starting to do it themselves.

This would be an obvious post with an obvious point, except that our cultural narrative hasn’t caught up to real trends. Mrs. Prudeshrew from Spittoon Falls praying in vain to exorcise Judy Blume from the library stacks is no longer a major threat to literature and art. Scolds, censors, control freaks, and prudes are now policing words and works from within, adopting the traditionally conservative position, anathema to them until recently, that certain books and art are virtuous while others are not, requiring the most enlightened and most orthodox to draw clear lines in the putative interests of everyone else. They’re toying with newfound privileges as censores librorum, empowering themselves to determine which creative works are sufficiently inoffensive to public faith and morals to deserve a nihil obstat.

This is why humans crave power. This is how most of us use it when we get it. None of this ever really changes. The assertions of moral superiority, this impulse to nail down sinners and damn the impure, all show that church ladies can come from anywhere, even with no church in sight. I’ll be watching to see if this timidity and moral preening get worse in literary and artistic circles. I want the doors of secular institutions to stay open to unorthodox, offensive, and literally irreverent ideas, without the precondition of a single profession of faith, while I still have the ghost of a choice.

(Avert your eyes! Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs, from Wikimedia Commons.)