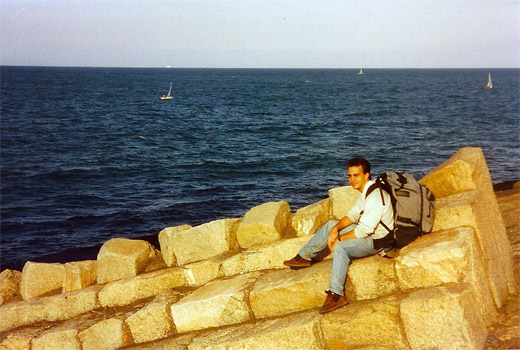

Twenty-five years ago, I did something I might not have considered if I’d been burdened with uncommon wisdom or more common sense: I rambled around Europe with my best friend, hauling nothing but clothes, a camera, the money in my pocket, and cassettes for my Walkman. We began with no direction, but we’ve steered by the memory ever since.

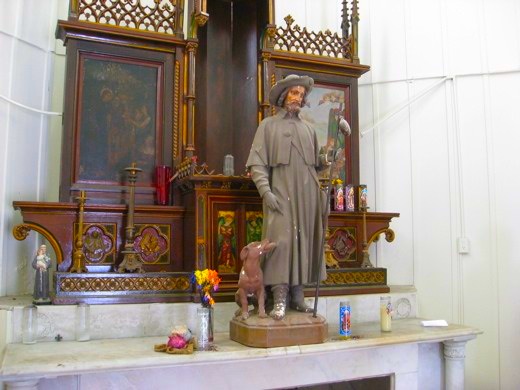

For weeks, we wandered. We hitchhiked. We let bus schedules and the number of hours till nightfall determine our actual route. We staggered through thunderstorms fifteen miles from bus stops into quiet little seaside towns. We crept with unease through moonlit medieval churchyards. We found lodging even when we didn’t speak the language, have money to spare, or smell like civilized humans. We befriended strangers who cooked us breakfast at midnight; we imposed on startled acquaintances and long-lost kin. We slept on the floors of bus stations and ferry terminals. We got robbed, we had a minor misunderstanding with law enforcement, and we babbled our way out of conflict. We met the gaze of an Irish sea captain who prophesied a dark doom for foreign pilgrims. We jumped Metro turnstiles in Paris, celebrated midsummer on a farmstead in Denmark, downed beer with a Swiss soldier, tried to sneak into a cathedral library in England, and scrambled up a hill in Scotland to watch the sun set over a cemetery on the summer solstice.

No GPS can lead us back to those places and moments in time. We covered hundreds of miles with only two or three maps and a sketchy, error-pitted guidebook―but no cell phones, no transatlantic ATMs, and surprisingly few places that took anything but cash, and rarely the coin of a neighboring realm. Clean, chirpy backpackers bounded through train stations as they flitted from city to city, cathedral to cathedral, but their fellowship never engulfed us. Greater misadventures awaited in dumps no guidebook author saw fit to recommend. Note to young travelers: If the stranger in the next bunk is moaning and wailing till morning, no one at the YMCA will think less of you if you sleep in your boots and perhaps keep a knife close at hand.

I flew home on a Saturday and reported on Monday morning to my job as an assistant account executive for a tax consultancy. From my window, there was little to look at but the nearby highway, but for the first time, the unseen world beyond it felt reachable and real.

Before the summer limps to its grave, we’ll unseal a plastic bag we’ve stowed away for nearly half our lives. It’s full of receipts, ticket stubs, and other evidence of mundane conversations that long ago gave way to myth. The past isn’t just tactile or visual; it had a scent, the hardest of memories to put into words. What unremembered mood might come wafting from those scraps? Medieval people had a nose for wonder: If they opened a tomb and were hit with a sweet, pleasant smell, they were in the presence of the sacred. We modern types love to laugh at that, but it’s easier to honor the truth in legends when you’ve lived through and crafted a few of your own.

When I see us grin in blurry photos, I’m tempted to wonder if our present circumstances live up to our long-ago hopes. No―the older and grayer I get, the more foolish that question becomes. We’ve continued to hike, climb mountains, and stumble through foreign lands, but those just aren’t the measure of life anymore. My friend now runs his own law firm, and he’s testified before Congress. Work has taken him from Nairobi to Jerusalem. He married someone who became a vital friend of mine in her own right, as are their kids. When we sit and talk, I see in their faces the past and the future at once.

Last summer, a ramble around New Jersey ended with both of us reluctantly appearing in a filmed endorsement for an Indian music store. I know nothing about Indian classical music; we just laughed and let it happen. It’s those dumb, sudden moments that feel most like youth, when happy confusion embraces the vain hope that you have an infinite series of wonderful riddles before you. Yes, something is always a few steps behind you, whispering falsehoods to lessen the joys on the narrowing pathway ahead. If you’re lucky, good people are still there beside you, and new ones have joined them who’ve heard all your stories but indulge their retelling. Listen to your own eager voice and hear what it long tried to make plain: you will never stop choosing how little difference there needs to be between looking forward and looking back.

Twelve hundred years ago tomorrow—January 28, 814—the Franks lamented the death of a tall, paunchy, mustachioed king whom they already knew was one of the most important people in European history: Karl or Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus, Charlemagne. His biographers cataloged the omens that presaged his death, and poets insisted that all the world wept for him. But they mourned too late; the old man they interred in the cathedral had long been lost to legend and myth.

Twelve hundred years ago tomorrow—January 28, 814—the Franks lamented the death of a tall, paunchy, mustachioed king whom they already knew was one of the most important people in European history: Karl or Charles the Great, Karolus Magnus, Charlemagne. His biographers cataloged the omens that presaged his death, and poets insisted that all the world wept for him. But they mourned too late; the old man they interred in the cathedral had long been lost to legend and myth. Tomorrow’s anniversary kicks off the

Tomorrow’s anniversary kicks off the  But take a second look: There’s a remarkable, complex person beneath centuries of rhetoric and legend. It’s the rare leader indeed who can smile at endless flattery, enjoying obsequious poems praising him as a second David, yet still demonstrate, through his actions, that he knows he isn’t the apotheosis of his civilization—that the future needs books, buildings, and institutions that endure.

But take a second look: There’s a remarkable, complex person beneath centuries of rhetoric and legend. It’s the rare leader indeed who can smile at endless flattery, enjoying obsequious poems praising him as a second David, yet still demonstrate, through his actions, that he knows he isn’t the apotheosis of his civilization—that the future needs books, buildings, and institutions that endure. “The origin of our city will be buried in eternal oblivion,” wrote Washington Irving in his satirical

“The origin of our city will be buried in eternal oblivion,” wrote Washington Irving in his satirical