This blog has been fallow for six months. I regret the silence, but not the reasons. I’ve gotten involved in three local nonprofits, including one whose leadership asked me to help them write a book. Theirs is the sort of worthwhile project a history-writer dreams about, I’m working with good people, and I can’t wait until we share the book with our neighbors and the world in 2020.

In the meantime, beyond my little bend in the river, I see authors, readers, and scholars apparently losing their minds. A week ago, young-adult author Sarah Dessen took exception to a college student who disparaged her work in a South Dakota newspaper in 2016. Dessen began to insult the kid on Twitter and drew forth an online mob of readers, authors, and publishers who joined her in harassment and intimidation.

Not content to let publishing win the Worst Industry of the Week award, the student’s alma mater, Northern State University, tweeted a craven apology, choosing to suck up to a bestselling author rather than defend―or even ignore―one alumna who said what she thought of a book.

Not content to let publishing win the Worst Industry of the Week award, the student’s alma mater, Northern State University, tweeted a craven apology, choosing to suck up to a bestselling author rather than defend―or even ignore―one alumna who said what she thought of a book.

Why were people invested in the young-adult fiction industry, which rakes in more than $3 billion a year, so quick to pounce on a lone, unknown student who expressed her taste in literature three years ago? Perhaps some readers and authors, living by expired cultural templates, can’t yet fathom that they stand in the mainstream and no longer wield the moral authority of underdogs. It may be meaningful that the loudest voices representing young-adult literature on social media aren’t adolescents but thin-skinned adults. Too many aspiring writers are also so keen to feel collegial with big-name authors that they’re inclined to join an author’s side, eager for the righteous rush of communal fandom. No doubt it’s corrupting for authors to have fans who look to them for meaning and purpose beyond what their books can provide. Fame, wealth, and flattery are disastrous in realms far beyond politics.

* * *

People who write and read are also, I’m finding, more put off by strange, skewed, and unsanctioned thoughts than they used to be.

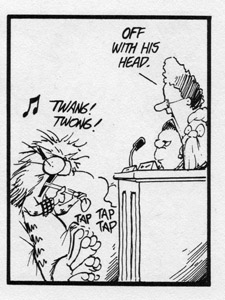

Decades ago, my middle-school interest in superhero comics eventually led me to pick up, every Friday for years, the weirdest indie comics on the shelves. The best and most engaging parts were the readers’ letters and rambling editorials. They read like the spillover from a mental storage unit packed to the ceiling with marginal notions and contrarian whims. We could regard the contents with amusement, step over them with discomfort, or root through them for our own purposes.

Delightfully, those commentaries didn’t slide smoothly into mylar bags of ideological simplicity. Their philosophical quirkiness would confuse and annoy today’s fans. In the past week, I’ve seen commentators and reporters react with confusion and annoyance to a 2017 interview with Alan Moore, the writer behind Watchmen, V for Vendetta, and other weirder, darker comics that somehow found homes with mainstream publishers in the ’80s. In the interview, Moore disavows his most famous work and warbles a rhapsody of challenging ideas:

What was the impact of popular heroes comic books in our culture? Why are people fascinated by alternative realities?

I think the impact of superheroes on popular culture is both tremendously embarrassing and not a little worrying. While these characters were originally perfectly suited to stimulating the imaginations of their twelve or thirteen year-old audience, today’s franchised übermenschen, aimed at a supposedly adult audience, seem to be serving some kind of different function, and fulfilling different needs. Primarily, mass-market superhero movies seem to be abetting an audience who do not wish to relinquish their grip on (a) their relatively reassuring childhoods, or (b) the relatively reassuring 20th century. The continuing popularity of these movies to me suggests some kind of deliberate, self-imposed state of emotional arrest, combined with an numbing condition of cultural stasis that can be witnessed in comics, movies, popular music and, indeed, right across the cultural spectrum. The superheroes themselves – largely written and drawn by creators who have never stood up for their own rights against the companies that employ them, much less the rights of a Jack Kirby or Jerry Siegel or Joe Schuster – would seem to be largely employed as cowardice compensators, perhaps a bit like the handgun on the nightstand. I would also remark that save for a smattering of non-white characters (and non-white creators) these books and these iconic characters are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race. In fact, I think that a good argument can be made for D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation as the first American superhero movie, and the point of origin for all those capes and masks.

I love this: never-asked questions about why adults are now so enamored of power fantasies developed for adolescent boys; a swipe at extruded corporate entertainment products; a wistful ode to creators’ rights voided by work-for-hire contracts; a non-sequitur jab at gun owners; and a call to comics fans to think about the historical and sociological implications of superheroes. People who can’t laugh off these notions, mull them over, or counter them might do well to ask themselves why they hold their positions on popular culture as closely as religious dogma.

And yet I doubt that superheroes “are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race,” and it’s too clever by half to claim that Birth of a Nation was “the first American superhero movie.” So what? Overstating causation doesn’t exclude the possibility of a connection. The creation of masked superheroes who operate outside or above the law overlaps with the era of the Klan’s masked “night riders” and comes not long after the raids of masked, costumed vigilantes in the “tobacco wars” in Kentucky and Tennessee (shown in the photo to the left).

And yet I doubt that superheroes “are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race,” and it’s too clever by half to claim that Birth of a Nation was “the first American superhero movie.” So what? Overstating causation doesn’t exclude the possibility of a connection. The creation of masked superheroes who operate outside or above the law overlaps with the era of the Klan’s masked “night riders” and comes not long after the raids of masked, costumed vigilantes in the “tobacco wars” in Kentucky and Tennessee (shown in the photo to the left).

Looking for the roots of American superheroes in a masked vigilante tradition may or may not pan out, but the idea is arguable. And even if he’s wrong here, in whole or in part, thank goodness for cranky old Alan Moore—because man, that’s a mind forever voyaging.

* * *

But then sometimes, complexity and ambiguity overwhelm those who work isn’t given to clarity. In September, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists fell apart over the place of “Anglo-Saxon” in the organization’s name and in scholarship in general. Amid debates about the term, which is used by racists and white supremacists outside of academia, members on both sides quit in disgust, and the organization is now nameless.

But then sometimes, complexity and ambiguity overwhelm those who work isn’t given to clarity. In September, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists fell apart over the place of “Anglo-Saxon” in the organization’s name and in scholarship in general. Amid debates about the term, which is used by racists and white supremacists outside of academia, members on both sides quit in disgust, and the organization is now nameless.

The name change strikes me as surrender to racists, who will only appropriate whatever term of art the scholars of early medieval England choose next. When I went looking for reasoned arguments from both sides, I didn’t make it past scholars on Twitter accusing each other of bad faith and bickering over who’s doing more “antiracist work.” (I’m not going to link to their babyish squabbles.)

I’ve been writing about medieval history for 20 years, and for a decade of that time I taught medieval literature, but the online arguments among medievalists about anti-racist activism remind me of a more modern moment: Gonzo in The Muppet Movie traveling to Bombay to become a movie star because you go to Hollywood only “if you want to do it the easy way.” While everyone is capable of doing good in their own classrooms, cubicles, or cul-de-sacs, if your believe your primary vocation is to smash racism but you became a professor of medieval literature or history…well, I just hope a bear and a frog in a Studebaker give you and your chicken a lift.