When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.”

When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.”

Even so, when I read Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, I hadn’t expected to see Sarah Hopkins Bradford liken her subject to one of the most complex figures of the Middle Ages, a saint, a warlord, a visionary, and a child—but there she is, on the very first page:

It is proposed in this little book to give a plain and unvarnished account of some scenes and adventures in the life of a woman who, though one of earth’s lowly ones, and of dark-hued skin, has shown an amount of heroism in her character rarely possessed by those of any station in life. Her name (we say it advisedly and without exaggeration) deserves to be handed down to posterity side by side with the names of Joan of Arc, Grace Darling, and Florence Nightingale; for not one of these women has shown more courage and power of endurance in facing danger and death to relieve human suffering, than has this woman in her heroic and successful endeavors to reach and save all whom she might of her oppressed and suffering race, and to pilot them from the land of Bondage to the promised land of Liberty. Well has she been called “Moses,” for she has been a leader and deliverer unto hundreds of her people.

By 1869, well-read Americans had tried to make sense of the Maid of Orleans. Mark Twain published Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc that same year; two years before, abolitionist and women’s-suffrage crusader Sarah Grimké translated a French biography of Joan into English. Somebody, somewhere, may have dimly recalled Female Patriotism, or the Death of Joan of Arc, a 1798 play by Irish-born newspaperman John Daly Burk. If these works have anything in common, it’s a sense of Joan of Arc as enviably childlike. Perhaps from there it was an easy leap to the paternalism that even open-minded white Americans felt about their black countrymen.

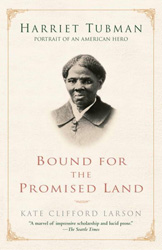

But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an engaging 2003 bio, Kate Clifford Larson provides a well-researched life of Tubman that offers glimpses of a Joan-like figure for anyone hoping to find them. Tubman was a nurse, a spy, and a scout during the Civil War, but she was also a warrior who led a daring and brutal raid on Confederate ships in South Carolina―and like Joan, and indeed like many memorable women and men of the Middle Ages, she was also a religious mystic.

But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an engaging 2003 bio, Kate Clifford Larson provides a well-researched life of Tubman that offers glimpses of a Joan-like figure for anyone hoping to find them. Tubman was a nurse, a spy, and a scout during the Civil War, but she was also a warrior who led a daring and brutal raid on Confederate ships in South Carolina―and like Joan, and indeed like many memorable women and men of the Middle Ages, she was also a religious mystic.

When Tubman was in her teens, an overseer threw a two-pound weight at a fugitive slave; he missed him, but hit Tubman square in the head. This freak accident, the source of lifelong pain, helped turn her into a fearless leader who inspired (and sometimes terrified) the people around her:

Tubman broke out, often unexpectedly, into loud and excited religious praising. If this injury caused her great suffering, it also marked the beginning of a lifetime of potent dreams and visions that, she claimed, foretold the future. Some of her dreams eventually took on an important role in Tubman’s life, influenced not only her own course of action but also the way other people viewed her.

Larson offers temporal lobe epilepsy as a scientific explanation for Tubman’s visions, but she stresses the need to understand the influence of African culture and evangelical Protestantism on what, to my mind, are visions that also wouldn’t be out of place in the Middle Ages:

Sounds of music, rushing water, screaming, and loud noises would overcome her without notice. Her dreams, visions, and hallucinations often intruded amid daily work and activities. “We’d be carting manure all day,” Tubman once explained to an interviewer, “and t’other girl and I was gwine home on the sides of the cart, and another boy was driving, when suddenly I heard such music as filled all the air.” Soon she began to experience a profound religious vision, “which she described in language which sounded like the old prophets in its grand flow.” Persistent shaking by her fellow slaves brought her back to reality, though she protested that she hadn’t been asleep at all.

[…]

Such experiences reinforced her notions of an all-powerful being that guided her through her life, protecting her and providing divine instruction. Tubman “used to dream of flying over fields and towns, and rivers and mountains, looking down upon them ‘like a bird.’” She claimed she had inherited this ability from her father, who “could always predict the weather, and that he foretold the Mexican war.”

I dug into the Tubman-Joan comparison and was surprised by how much there was to find―but less surprised that the notion thrived and faded with trends in the culture at large.

Bradford likened Tubman to a white European warrior-saint in 1869. That makes sense: Before the Civil War, Joan of Arc turns up in one of the most important cultural magazines for budding Confederates, the Southern Literary Messenger. She’s the subject of a romantic poem that calls for national defense, and in a bitter, blustery review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin she’s the exemplar of everything Harriet Beecher Stowe is not, an “unsexed” knight whose chivalry gives her a rare exemption from having to act like a lady.

By the time Bradford wrote Tubman’s bio, though, chivalry was up for grabs. The Civil War was over. Black Southerners were heading to Congress, and the Freedmen’s Bureau sought to educate former slaves, some of whom helped draft new state constitutions. Abolitionists and African Americans and radical northern Republicans all must have marveled as racial taboos and prejudices looked ready to collapse. Casting Tubman as Joan of Arc didn’t just pay tribute to her complexity; it also acknowledged that she was comparable to white people and fully human, perhaps even superhuman―and it tweaked conquered Confederates as well.

The comparison caught on. An 1896 profile of Tubman in The Woman’s Era, an African-American newspaper, picks it up without apology:

So at the very beginning of this new day let us all meet in the benign presence of this great leader, in days and actions, that caused strong men to quail this almost unknown, almost unsung “Black Joan of Arc” . . . The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witness of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.

But that’s the black press; white readers may have felt otherwise.

Suddenly it’s 1897. Reconstruction has failed. Racist white Democrats have prevailed in the South; Civil War veterans are already holding genial North-South reunions; all eyes are on railroads and the West; and a country obsessed with business and finance is starting to haul itself out of a four-year depression. Sarah Hopkins Bradford revises and reissues her Tubman biography as Harriet, the Moses of Her People. Deprived of the dignity of a surname in the new title, Tubman is now quoted in dialect, and her sharp edges have been bravely bent down and taped over. Such is the national spirit of compromise. Tubman is still Joan of Arc, but Bradford, flaunting her own refinement, now calls her “Jeanne D’Arc.” Since the comparison pleases her, she trots it out a second time:

Her color, and the servile condition in which she was born and reared, have doomed her to obscurity, but a more heroic soul did not breathe in the bosom of Judith or of Jeanne D’Arc.

There’s heroism and praise in Bradford’s revision, but she no longer makes the page-one Harriet-Joan connection “advisedly and without exaggeration.” A woman who once “deserves to be handed down to posterity” is now “doomed…to obscurity.” Within a few years, comparisons to a medieval European saint will start to bother white writers, even when Tubman impresses them―as in a 1907 article in the New York Herald that got picked up by newspapers nationwide:

There is not a trace in her countenance of intelligence or courage, but seldom has there been placed in any woman’s hide a soul moved by a higher impulse, a purer benevolence, a more dauntless resolution, a more passionate love of freedom. This poor, ignorant, common looking black woman was fully capable of acting the part of Joan d’Arc.

Look at what’s happened: In four decades, comparing Harriet Tubman to Joan of Arc has gone from natural and straightforward to unlikely and ironic. At best, Joan is a “part” she was able to act.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Americans formed their own secular cult of Joan. French nationalists rallied round the saint in 1870 after the humiliating loss of Alsace-Lorraine to the Prussians. Americans, looking to Europe for trends, were beguiled by her purity, her simple faith, her romantic communion with nature. In 1915, a statue of Joan got its own park in Manhattan. Determined to out-spectacle D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. De Mille released his movie Joan the Woman the following year. Joan was drafted during World War I, serving as a model soldier and the subject of poems and articles in Stars and Stripes. A illustrated biography for children hit the shelves in 1918, and her equestrian statue first looked across D.C. from Meridian Hill Park in 1922.

At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to Kate Clifford Larson, by the time a well-intentioned radical started researching a new biography of Harriet Tubman in 1938, publishers shooed him away. Random House in particular “balked at her being compared to Joan of Arc.”

At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to Kate Clifford Larson, by the time a well-intentioned radical started researching a new biography of Harriet Tubman in 1938, publishers shooed him away. Random House in particular “balked at her being compared to Joan of Arc.”

Joan of Arc was quite a few things Harriet Tubman was not, and vice-versa. Tubman wasn’t a child hero, a martyr, or a national symbol. In fact, Larson’s bio shows that she wasn’t like anyone else; she deserves to be remembered in all her complex and baffling humanity. Still, it’s remarkable that for a few promising years, comparing Tubman to a visionary child warrior saint felt right and just. That we’re now surprised by a colorblind metaphor doesn’t speak well of the century since.

A knight sliced in half like a sesame bagel, a saint tossed down a hillside in a barrel lined with nails—pain is an ageless wellspring of humor, but we were too weirdly willing to laugh. As graduate students, we were honing our sense of which aspects of the Middle Ages were born of certain eras and places and which others were timelessly human. Yet something about the classroom made the medieval world harder for me to imagine. The line of scholars whose work helped us understand the past in the first place also stood in the way of a gut-level sense of real people’s lives. Then the violence was never real, only a source of other people’s pictures or words, like an idealized painting or flippant cartoon.

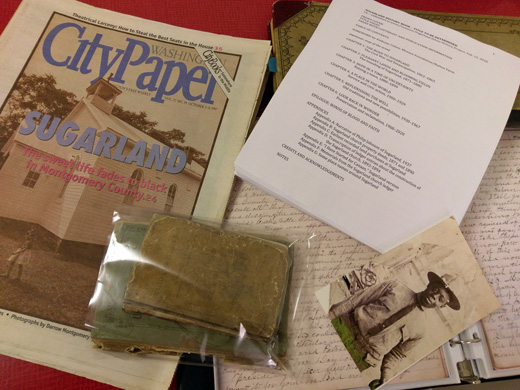

A knight sliced in half like a sesame bagel, a saint tossed down a hillside in a barrel lined with nails—pain is an ageless wellspring of humor, but we were too weirdly willing to laugh. As graduate students, we were honing our sense of which aspects of the Middle Ages were born of certain eras and places and which others were timelessly human. Yet something about the classroom made the medieval world harder for me to imagine. The line of scholars whose work helped us understand the past in the first place also stood in the way of a gut-level sense of real people’s lives. Then the violence was never real, only a source of other people’s pictures or words, like an idealized painting or flippant cartoon. Last month, our town

Last month, our town

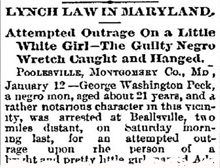

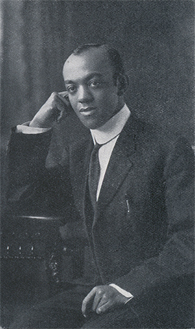

Poets pray for remembrance on the pages of an anthology—but whenever I saw Fenton Johnson’s poems in collections of African American verse, the selections were too limited for me to get a real sense of him. Fond of forgotten writers, I tracked down more of Johnson’s work to find out who he was and what he had hoped to become. My search only brought me back to his most anthologized poem, which takes on new meaning amid echoing debates about the medieval-ness of all things American.

Poets pray for remembrance on the pages of an anthology—but whenever I saw Fenton Johnson’s poems in collections of African American verse, the selections were too limited for me to get a real sense of him. Fond of forgotten writers, I tracked down more of Johnson’s work to find out who he was and what he had hoped to become. My search only brought me back to his most anthologized poem, which takes on new meaning amid echoing debates about the medieval-ness of all things American.

I hopped the barbed hedge of graduate school more than 20 years ago, but the burrs and brambles of medieval thinking still cling to my life. I never know if they’re brittle twigs, best brushed off and swept away, or green sprigs that can be woven into some new, small, useful thing. Take “Deor,” an Old English poem that puts on thorns at the strangest of times—even when I’m reading about a different culture thousands of miles away and a millennium later.

I hopped the barbed hedge of graduate school more than 20 years ago, but the burrs and brambles of medieval thinking still cling to my life. I never know if they’re brittle twigs, best brushed off and swept away, or green sprigs that can be woven into some new, small, useful thing. Take “Deor,” an Old English poem that puts on thorns at the strangest of times—even when I’m reading about a different culture thousands of miles away and a millennium later. My student’s speculations about “Deor” sprang to mind, unexpectedly, as I read

My student’s speculations about “Deor” sprang to mind, unexpectedly, as I read  None of this hasn’t been pondered for ages by much smarter people, but in the years since my student asked her question blessedly unimpeded by assumptions, few new opinions have formed about “Deor.” The author of

None of this hasn’t been pondered for ages by much smarter people, but in the years since my student asked her question blessedly unimpeded by assumptions, few new opinions have formed about “Deor.” The author of  When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.”

When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.” But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an

But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an  At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to

At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to

When the U.S. Postal Service

When the U.S. Postal Service