They told me, “You have to watch this interview where Mike Tyson talks about medieval history,” and so I did, and there he was at the New York Public Library in 2013 being interviewed by curator Paul Holdengräber, whose German accent strikes the American ear as both effortlessly intellectual and lightly amusing, and who would seem to have nothing in common with the face-tattooed boxer.

The two men do, in fact, find much to talk about. Their discussion is mesmerizing, because to most of us Mike Tyson is nothing but a face and fists, not a man who reflects aloud and at length about his inner life. Holdengräber prompts a reticent Tyson to narrate clips of his greatest moments in the ring, and newcomers to boxing will easily see why Tyson was such a sensation, but Iron Mike grows more animated when other matters arise.

Half an hour into the interview, Holdengräber says that their mutual friend, eccentric German filmmaker Werner Herzog, urged him to ask Tyson why he’s so fascinated by Clovis, the founder of the Merovingian Frankish dynasty, and Pepin the Short, the first Carolingian king of the Franks. Tyson’s answer, however halting, makes him come alive:

I don’t know—it all comes from my insecurity from being poor, and not having enough—to be insecure, and being—yeah, that’s what it is: obscure. I never wanted to be obscure. I was born in obscurity and I never wanted to deal with that again, never wanted to be that. And they came from obscurity.

Tyson then narrates a capsule history of the Frankish kings. He rambles, he doesn’t get all the details right, and his mispronunciation of names marks him as an autodidact, but it’s a shame to hear the audience laugh when Holdengräber asks, “Mike, how do you know all this shit?” Whether Tyson is mapping his own experiences onto medieval history or hearing echoes of the Franks in his troubled life, the credentialed, status-conscious audience is uncomfortable with his sincere interest in a past they find trivial.

Yet Tyson is the real deal, a book lover not because his peer group yaks about whichever author the New York Times has dubbed fame’s latest love child, but because he’s hungry for ideas, for meaning, for connections across time. He speaks with undisguised emotion about Cus D’Amato, the trainer and manager who turned him into a lethal boxer. Obsessed with Nietzsche and Clausewitz, D’Amato taught Tyson to see boxing as war and war as the key to decoding the world. “That is just what I do,” Tyson explains, an attentive pupil and dutiful son. “I love war. I love the act of war. I love the players in war, the philosophy of war.”

Tyson is searching for more than war on the pages of the past. Having grown up amid crime and chaos and founded his life on violence, he now relies on books to make moral and ethical sense of the world:

Yeah—they’re our most priceless possessions, because if you think about it, you know, a room without a book is like a body without a soul. It’s the only way that we can connect the future with the past. Without that, there’s no way that we can know about the future, and know about particularly the past, or the present, you know, that when you think about history, the value of history is not necessarily scientific but moral. By liberating our minds and deepening our sympathies and fortifying our will, we can control—pretty much history allows us to control not society but ourselves, which is a much more important thing to do, you know what I mean? And it would allow us to pretty much meet the future more so than foretell it, and for that reason alone, in order to predict the future we always have to look through the past, because very rarely does time not repeat itself, and it always will repeat itself.

I’ve heard a quote before in a book that we would be fools to think historically that the past is us in funny clothes, but the past is us in funny clothes, and that’s truly what it is. That’s from somebody who really said a really profound statement but he misquoted what he was saying, he must have been saying it backwards, because that’s really what the past was, it’s just us in funny clothes, in different times, that’s really what it is.

Of course, to hear Tyson cite a quip inaccurately attributed to Cicero, “a room without books is like a body without a soul,” is to wonder if he’s putting us on. Late in the interview, he jokes that if you quote books, you fool people into thinking you’re smart—but Tyson, for all his malapropisms and mispronunciations and odd mannerisms, is intelligent. He’s going round after round with big questions that many of the ostensibly educated attendees at his book-talk don’t bother to ask.

When Holdengräber suggests that Tyson’s knowledge of history didn’t improve his behavior, Tyson calmly disagrees. He compares himself to the fictional Ben-Hur, a fellow athlete and celebrity who achieved glory but was doomed to be unfree until he set his priorities in order: “He may not have been famous again,” Tyson points out, “but he got his family, and that was his success.”

After listening to Mike Tyson—childhood criminal, devastating fighter, struggling alcoholic and recovering drug addict, convicted rapist, pop-culture eidolon—speak for an hour and a half, I still don’t quite know who he is. He may be the closest thing 21st-century America has to a Robert E. Howard character, a born barbarian who’s ignorant of social niceties but possesses earned wisdom that the civilization around him disdains. I don’t know whether he’s all in on his bookish pursuits or one slight away from again gnawing off someone’s ear. Whether he’s a good man or a bad man feels foolish to ask about a professional punch-thrower who reads Nietzsche, but Tyson looks like a better man, one who has perhaps searched harder for his humanity than the onlookers snickering from the safety of their library seats. What has their pride gained them? Tyson’s, by contrast, has brought him perspective, and with it the humility to admit that his story is still being written—and has been before.

Throughout the day I heard many melodramatic and sentimental pronouncements, most of them by commentators who don’t know much about the history of Notre-Dame. You don’t have to be an expert on the cathedral to appreciate that its survival since the Middle Ages is itself a marvel. By the 18th century, many of its gargoyles had disintegrated or were worn into stumps. Statues over the lintel depicting the dead rising from their graves came down in the 1770s, allowing royal processions to fit more easily through the doors; revolutionaries then denuded the cathedral of statues and artwork that had enshrined cléricalisme and féodalité. Ham-handed attempts to “fix” Notre-Dame in the early 1800s by attaching new stone with quick-rusting iron pins only made the building less structurally sound.

Throughout the day I heard many melodramatic and sentimental pronouncements, most of them by commentators who don’t know much about the history of Notre-Dame. You don’t have to be an expert on the cathedral to appreciate that its survival since the Middle Ages is itself a marvel. By the 18th century, many of its gargoyles had disintegrated or were worn into stumps. Statues over the lintel depicting the dead rising from their graves came down in the 1770s, allowing royal processions to fit more easily through the doors; revolutionaries then denuded the cathedral of statues and artwork that had enshrined cléricalisme and féodalité. Ham-handed attempts to “fix” Notre-Dame in the early 1800s by attaching new stone with quick-rusting iron pins only made the building less structurally sound. Thanks to Victor Hugo’s efforts to lobby the July Monarchy in the 1830s, the French state agreed to fund restoration efforts, and architects Viollet-le-Duc and Lassus began to rescue the building in the 1840s. They turned a husk back into a cathedral, and their work was so convincing that the world largely forgot that Notre-Dame had ever been in shambles.

Thanks to Victor Hugo’s efforts to lobby the July Monarchy in the 1830s, the French state agreed to fund restoration efforts, and architects Viollet-le-Duc and Lassus began to rescue the building in the 1840s. They turned a husk back into a cathedral, and their work was so convincing that the world largely forgot that Notre-Dame had ever been in shambles.

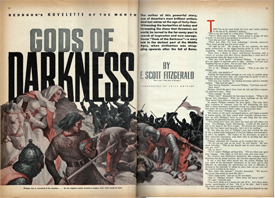

Six years passed between the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third “Philippe” story and the fourth and final entry in the series. By the time “Gods of Darkness” debuted in the November 1941 issue of Redbook―which hailed the seven-page sketch as its “novelette of the month”―Fitzgerald had been dead for almost a year.

Six years passed between the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third “Philippe” story and the fourth and final entry in the series. By the time “Gods of Darkness” debuted in the November 1941 issue of Redbook―which hailed the seven-page sketch as its “novelette of the month”―Fitzgerald had been dead for almost a year.  Despite his oppressive deadpan, Fitzgerald tries here and there to be playful, to no real end. “In less time than it has taken to describe Philippe’s bodyguard, he met the approaching party,” he writes at one point, a wink from a narrator who rarely steps forward with thoughts. I’m not the first reader to wish that the Philippe stories were filtered through the eyes of an observer, a ninth-century Nick Carraway who could have given Fitzgerald’s version of the Middle Ages a solid sense of place.

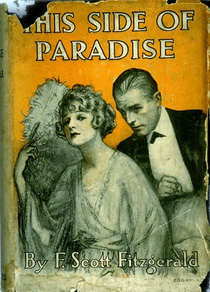

Despite his oppressive deadpan, Fitzgerald tries here and there to be playful, to no real end. “In less time than it has taken to describe Philippe’s bodyguard, he met the approaching party,” he writes at one point, a wink from a narrator who rarely steps forward with thoughts. I’m not the first reader to wish that the Philippe stories were filtered through the eyes of an observer, a ninth-century Nick Carraway who could have given Fitzgerald’s version of the Middle Ages a solid sense of place. The Philippe stories might be more revealing if we read them alongside Fitzgerald’s other work. After the letdown of “Gods of Darkness,” I turned back to

The Philippe stories might be more revealing if we read them alongside Fitzgerald’s other work. After the letdown of “Gods of Darkness,” I turned back to  F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third story about medieval France “shows that national chaos does not fail to bring forth a leader.” That’s the chirpy editorial comment just below the byline in the August 1935 issue of Redbook, and it makes me wonder if the magazine’s staffers actually read the story. By this point, they’re no longer touting Fitzgerald’s contributions on the covers, so readers would have had to stumble upon “The Kingdom in the Dark” while flipping through an issue already packed with other, lighter fiction. I wonder how many of them even remembered

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third story about medieval France “shows that national chaos does not fail to bring forth a leader.” That’s the chirpy editorial comment just below the byline in the August 1935 issue of Redbook, and it makes me wonder if the magazine’s staffers actually read the story. By this point, they’re no longer touting Fitzgerald’s contributions on the covers, so readers would have had to stumble upon “The Kingdom in the Dark” while flipping through an issue already packed with other, lighter fiction. I wonder how many of them even remembered  “But Philippe was wasting his passion,” Fitzgerald writes. “Three days later Louis the Stammerer, King of the West Franks, obligingly died.” That’s the final line of the story, a conclusion that snuffs out whatever embers of tension and conflict that Fitzgerald has spent nine pages struggling to kindle.

“But Philippe was wasting his passion,” Fitzgerald writes. “Three days later Louis the Stammerer, King of the West Franks, obligingly died.” That’s the final line of the story, a conclusion that snuffs out whatever embers of tension and conflict that Fitzgerald has spent nine pages struggling to kindle. When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.”

When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.” But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an

But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an  At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to

At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to  No matter the ground that’s granted to you,

No matter the ground that’s granted to you,

My tarasque is likewise domesticated—or at least domestic. Back in February, when the aforementioned loved one and I were in Memphis, an ice storm shut down the city. We were lucky to be stuck indoors with an assortment of local beer, including the

My tarasque is likewise domesticated—or at least domestic. Back in February, when the aforementioned loved one and I were in Memphis, an ice storm shut down the city. We were lucky to be stuck indoors with an assortment of local beer, including the

In his 2009 book

In his 2009 book

Le stryge is the only Notre-Dame chimera who makes that Home Alone gesture, and the birdlike face of this second monster only somewhat resembles one actual creature on the cathedral. This baggage-sentinel seems to be Terry Allen’s own invention, a horror that might exist if late one night, weary from another day of menacing glares, le stryge and his fellow chimera threw back too much Beaujolais nouveau, discovered a shared adoration of Edith Piaf, and one thing led to another…

Le stryge is the only Notre-Dame chimera who makes that Home Alone gesture, and the birdlike face of this second monster only somewhat resembles one actual creature on the cathedral. This baggage-sentinel seems to be Terry Allen’s own invention, a horror that might exist if late one night, weary from another day of menacing glares, le stryge and his fellow chimera threw back too much Beaujolais nouveau, discovered a shared adoration of Edith Piaf, and one thing led to another…

Notre-Dame de Paris! Its gargoyles are iconic—especially the bitter critter on the cover of this book—but even many medievalists aren’t aware that he and 53 of his fellows aren’t medieval at all, but the products of an ambitious 19th-century restoration.

Notre-Dame de Paris! Its gargoyles are iconic—especially the bitter critter on the cover of this book—but even many medievalists aren’t aware that he and 53 of his fellows aren’t medieval at all, but the products of an ambitious 19th-century restoration.