In October, a rare free weekend surprised me. I put aside the books I’m drafting, asked everyone who relies on me to grant me a few selfish days, and drove nine hours north and thirty years into the past.

I barely recall how, but I once spent 16 unhappy months in New Hampshire, where a dead-end graduate program drained me, and bookstores kept me sane. In my dim, distorted memory, every crossroads held the promise of a grimy old house or dilapidated barn with a mumbly, gloved proprietor deep in reading, as if books held back the biting wind.

My first morning made me wonder if I’d ever lived there at all. Roads I thought went north went south. The grocery store wasn’t where I’d left it. The nearest small city, quaint and quiet in the ’90s, now bustled with luxury. The wood-paneled seminar room where I learned Old English and read Beowulf was now an office hallway, swa hit no waere. And most of the bookstores were gone.

Most, but not all. I drove west, on roads with views as gorgeous as they were unfamiliar. The turnoff into tiny Henniker nudged a memory, and I heeded it: Pass through town, bear right at the memorial and town hall, and head up the hill to the woods.

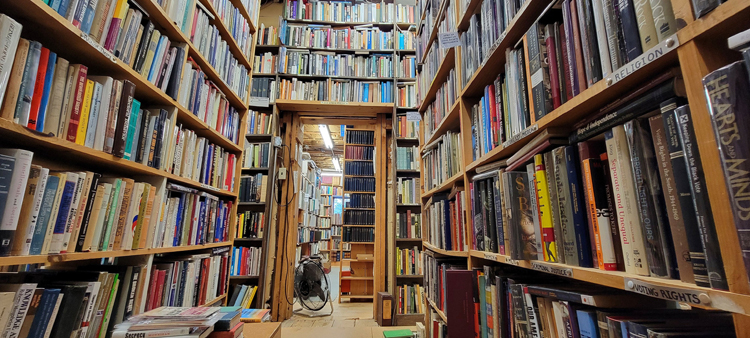

Marked only by a windworn sign, posing as just another farmhouse, was—and is—the platonic form of the rural used bookshop: the Old Number Six Book Depot.

The outside world, new and strange, no longer mattered. Stepping inside Old Number Six—its thick barn-and-book smell, the visual overload, the promise that anything might wait on its shelves—flung me, like a whirl of wind and wings, back to a very real 1994.

I’ve been to some great secondhand bookstores, some of them as large as Old Number Six, many in just as unlikely locations, yet Old Number Six outshines them. It’s even more glorious than I remembered. There’s not a single subject that isn’t represented on its two vast floors. The shelves are so densely packed that you need to go upstairs just to get a faint cell-phone signal—on the off chance the books briefly cease to beguile you. So many words and thoughts amid such provident silence: You start to understand why revelations of the infinite must awe the human mind.

Although whiter of beard and harder of hearing, the proprietor is the same fellow who sold me piles of books in the early 1990s: reticent but kindly, with a granite resistance to compliments. For thirty years, I’ve worked, traveled, written, moved, and chased down opportunities that would have been unimaginable in the drear of 1994. All the while, 363 days a year, he’s been at his desk, with an air of contentment born of duty, like some cosmic guardian of knowledge.

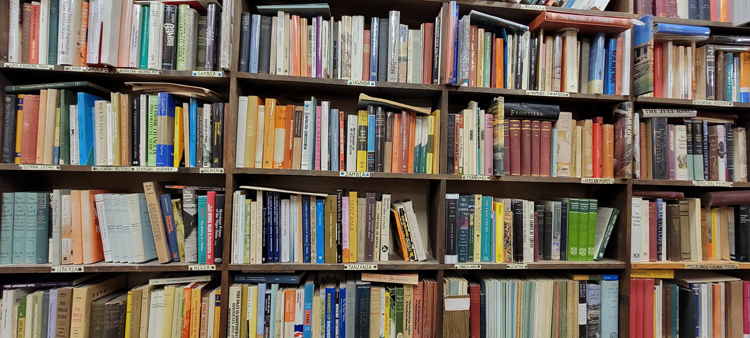

He claims to have 160,000 books, but I’m confident he has at least three times that many, and they’re organized with care. He doesn’t lump together all books about Africa, for example, but meticulously classifies them by country or culture—so if you’re looking for books only about Lesotho, Benin, or Guinea-Bissau, he’s made the search easy for you.

As I paid for my books after hours of browsing, I mentioned that the only difference I saw after thirty years was that he had moved the checkout desk to the opposite side of the entryway to make space for more shelves. He gave me a benevolent look and replied, after a pause, like an archangel of Yankee understatement: “Well, it has been a while.”

Indeed—but when so much has changed that the past feels full of false or fleeting memories, I found tons of old paper holding it steady, holding it down, giving it ballast to keep it from blowing away. And I turned back to the present, pleased at last with where I’d been.