On Sunday mornings, the ringing of church bells rolls right down the side-streets and echoes through the bushes and trees. Heed their call and hike up the hill; at the top you’ll find a gothic cathedral. Stunning in its own right, it also looms over one of Washington’s prettiest places: the Bishop’s Garden, a thriving reminder of 14th-century monastic life.

In one corner of the garden is something even older: an anachronism within an anachronism, a massive stone baptismal font encircled by special plants. This little “garden room,” a small sign explains, is here to evoke the ninth century, with each leaf and shoot a living monument to the era of Charlemagne. The emperor might have approved, in passing, of this collection of flowers and herbs. But twelve centuries later, its existence owes less to Charlemagne and more to the legacy of a mostly forgotten man, a monk named Walahfrid Strabo.

Walahfrid first beheld Reichenau at the age of eight. His parents were humble and poor, but the brothers on the island in Lake Constance saw promise in this strange little boy, this strabo—this “squinter”—who readily took to the life of the mind. In his later writings, he wryly recalled his barbaric roots, but the library at Reichenau was truly where Walahfrid Strabo was born.

Walahfrid’s heart never left that quiet island, not even after he was sent to Fulda for further study, nor during his nine years at Aachen, where he tutored Charles, the son of Emperor Louis. In 838, when Louis rewarded Walahfrid with an abbacy, the monk, then thirty, went home to Reichenau at last. Except for two years of political exile and the occasional diplomatic mission, Walahfrid spent the rest of his brief life there. In the decade left to him, he polished his poems, he wrote to a scandalous friend, and he worked, when he could, in his garden.

We know about the garden because of one poem: Walahfrid’s 444-line De Cultura Hortorum, “On the Cultivation of Gardens,” now more commonly known as his Hortulus, “the little garden.”

In a lively preface, Walahfrid exhorts others to share his commitment to gardening:

For whatever the land you possess, whether it be where sand

And gravel lie barren and dead, or where fruits grow heavy

In rich moist ground; whether high on a steep hillside,

Easy ground in the plain or rough among sloping valleys—

Wherever it is, your land cannot fail to produce

Its native plants. If you do not let laziness clog

Your labor, if you do not insult with misguided efforts

The gardener’s multifarious wealth, and if you do not

Refuse to harden or dirty your hands in the open air

Or to spread whole baskets of dung on the sun-parched soil—

then, you may rest assured, your soil will not fail you.

Although bookish by nature, Walahfrid makes clear that he is not merely transmitting found knowledge:

This I have learnt not only from common opinion

And searching about in old books, but from experience—

Experience of hard work and sacrifice of many days

When I might have rested, but chose instead to labor.

With quiet joy, Walahfrid walks the reader through his garden, a former mess of nettles and weeds now made useful and neat through careful springtime tending. His tour leads past rows of long-necked poppies, brilliant purple irises, pungent rue, and sprigs of fragrant mint. At every step, he catalogs the practical uses of his garden plants: wormwood, he claims, can cure a headache; fennel loosens the bowels, and it cures a cough when added to wine.

But Walahfrid’s thoughts range far beyond his humble garden, and his Hortulus is a fertile bed of budding notions. In sage, when new growth chokes its old leaves, Walahfrid sees “the germ of civil war.” Gourd-vines remind him of shields, ladders, and girls spinning wool; he admires their tenacity in a storm, and he marvels at how they aspire “to grow high from a humble beginning.” He points out that horehound counteracts the poisons of an evil stepmother, while pennyroyal lets him marvel at God’s bounty and contemplate the economics of scarcity. In a fit of Virgilian whimsy, Walahfrid even invokes the Muse, “who in sacred song / Canst stablish monuments of mighty wars / And mighty deeds,” all so he can more eloquently praise the heartburn-reducing properties of chervil.

Practical advice and classical flourishes, political allegory and good humor, philosophical musings and mock-epic—here and there, modest ideas and tender allusions break through the surface of the Hortulus, intertwine a little, and grow toward nothing in particular. In the end, Walahfrid’s garden path leads to the lily and the rose, Christian symbols both, each leaning against the other; he spots them just as he begins to tire. It would be odd indeed if a ninth-century abbot did not end his gardening book in this way—but it is odd already that Walahfrid has left this literary garden, in which he glimpses all creation, at fewer than 500 lines.

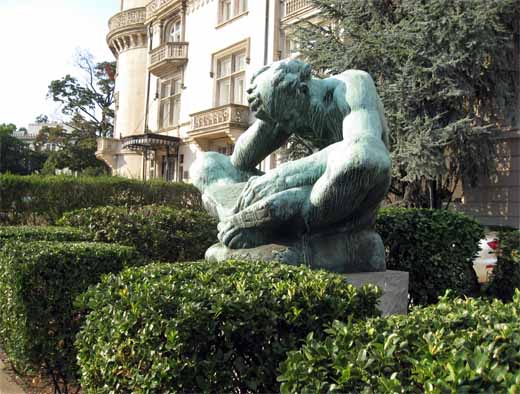

To understand Walahfrid’s brevity, close his Hortulus. Tuck it under your arm, pass beneath the open archway, and visit the real hortulus, which blooms in the shadow of a cathedral that Walahfrid never could have imagined. Here grows rosemary; here grows the fleur de lys; here grow fennel, black cumin, and green-leafed Gallic rose. In patches, bowing in their raised beds, the flowers and herbs surround the baptismal font, while around them grows a larger garden still.

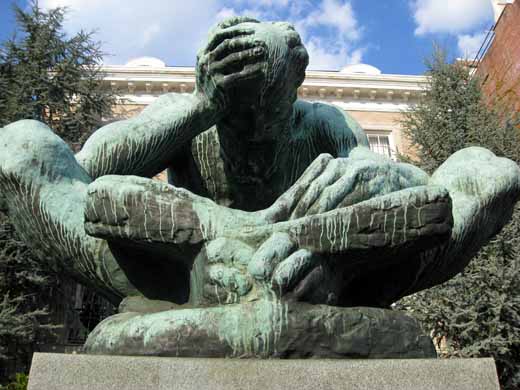

Tourists and pilgrims walk its stone-paved paths. Beautiful women lounge on benches and bathe in the sun. Toddlers rush for the goldfish pond, while clergy lead visiting dignitaries beyond the bushes and bees. Across the lawn, and frozen in stone, a father forgives his lost son.

Sit and sweat in the swampy heat. Relish this riot of flowers and bushes and vines. Savor every scent. And look, if you can, for the gardener.

Squint, and you’ll see him; he peers back at you across twelve hundred years. He lives in the dear freshness of this garden, where his work is remembered by those who now spend their mornings exactly as he did: spreading dung, contending with vermin, and tending to fistfuls of moist, fragrant soil.

Squint, and you’ll see him; he peers back at you across twelve hundred years. He lives in the dear freshness of this garden, where his work is remembered by those who now spend their mornings exactly as he did: spreading dung, contending with vermin, and tending to fistfuls of moist, fragrant soil.

He wonders why your hands aren’t hardened by labor; then he glimpses his book. His smile is kind, but his glare is reproachful. He is, after all, an abbot.

“A poem is only a poem,” he tells you, his voice made tender by time, “but a garden, dear brother, is art.”

Squint, and you’ll see him; he peers back at you across twelve hundred years. He lives in the

Squint, and you’ll see him; he peers back at you across twelve hundred years. He lives in the  A while back, my

A while back, my