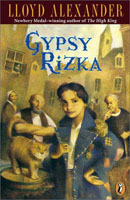

[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the “Lloyd Alexander” tag.]

Lloyd Alexander described Gypsy Rizka best. “The main character is a young half-gypsy girl named Rizka, as the title says,” he told Scholastic in 1999:

Lloyd Alexander described Gypsy Rizka best. “The main character is a young half-gypsy girl named Rizka, as the title says,” he told Scholastic in 1999:

She is so bright and smart and sassy and clever that she outwits the solemn and overblown townsfolk who are trying to do her in. It’s a very funny book because Rizka’s schemes—and she’s brilliant at them—are very comical. I should add that she always wins! And those idiot town dignitaries always lose, which is exactly the way it ought to be.

In this preview for young readers, Alexander highlights the most charming aspect of Gypsy Rizka; he also points out the novel’s significant flaw.

Considered a blot on Greater Dunitsa by the ruling elite, Rizka lives in a wagon on the edge of town. While she waits for her father to return with the rest of the gypsies, she sneaks around town with her tomcat and finds a father figure in the local blacksmith, the only person in Greater Dunitsa who’s even remotely sensible. Rizka, for her part, is implausibly competent: when she plays matchmaker, she unites two feuding families and finds homes for five stray kittens; she out-argues the local magistrate in court; she becomes the unofficial town doctor; and when an absurd law against insulting other people lands the entire fleabag aristocracy of Greater Dunitsa in the town’s only jail cell, Rizka is appointed mayor—and shows the good sense to abdicate for the sake of the greater good.

As the locals bicker, assert themselves, put on airs, and go about their pompous, petty lives, Alexander makes clear that disorder and discord are inevitable symptoms of human nature. Supernaturally clever, Rizka rises above it all, dispensing justice and righting wrongs. Her confidence never falters, and her outlandish schemes never fail. The world of Gypsy Rizka is, of course, inherently comic, but the residents of Greater Dunitsa are presented as fools right from the start; Rizka easily humiliates them, and she never faces any real danger. Alexander may have delighted in a heroine who “always wins,” but her perfection obviates any real dramatic tension.

Fortunately, Alexander also delights in the telling. He describes Rizka as “skinny as a smoked herring; long-shanked, bright-eyed, with cheekbones sharp enough to whittle a stick.” Beginning authors who try to convey character through clothing could learn from his concise, witty descriptions:

Rizka wore her usual costume: a pair of homeless breeches she had rescued; boots cracked and split, hardly a memory of their former selves; an old army coat so outnumbered by patches the original garment had surrendered; her black hair tied with a string; a felt hat cocked on top.

A goulash of indeterminate Slavic, Germanic, Hungarian, and generically Balkan ingredients, the ramshackle town of Greater Dunitsa serves as a fine stage for a shabby comic retelling of Romeo and Juliet, and the perceptive reader may notice a nod or two to Chaucer’s “Miller’s Tale.” As in fabliau, the locals are amusingly provincial: Only one resident, the local war hero, has ever been outside of town, and the city fathers think nothing of putting a cat on trial for burglary. Smiling all the way, Alexander skirts the issue of human evil, asserts the harmlessness of fools, and opts for a comic conclusion: “No one’s as bad as they seem—or as good as they think they are.”

The weekend I discovered Gypsy Rizka in a secondhand bookshop, The Economist published a disheartening report on “the dismal lives and unhappy prospects of Europe’s biggest stateless minority,” the Roma. If you’ve seen real gypsies on the streets of Eastern Europe, you’ve surely never seen a Rizka. The gulf between the lives of actual Roma and the whimsical gypsies of literature is a worthwhile subject, but it’s primarily a concern for adults, who can’t help but sigh over fiction. Gypsy Rizka is a charming book for the way it captures the fantasy of a child: the wish to get one over on the grown-ups.