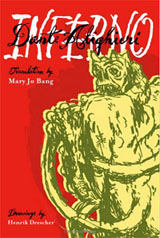

“Imagine a contemporary translation of Dante that includes references to Pink Floyd, South Park, Donald Rumsfeld, and Star Trek,” writes Zachary Lazar at BOMB magazine, praising poet Mary Jo Bang’s new version of the Inferno, which debuted on August 7. As Cynthia at the Book Haven points out, Alexander Nazaryan at the New York Daily News also enjoyed the book, while in a long and far less positive piece for the Wichita Eagle, Arlice Davenport argues that we shouldn’t call this sort of adaptation a translation:

“Imagine a contemporary translation of Dante that includes references to Pink Floyd, South Park, Donald Rumsfeld, and Star Trek,” writes Zachary Lazar at BOMB magazine, praising poet Mary Jo Bang’s new version of the Inferno, which debuted on August 7. As Cynthia at the Book Haven points out, Alexander Nazaryan at the New York Daily News also enjoyed the book, while in a long and far less positive piece for the Wichita Eagle, Arlice Davenport argues that we shouldn’t call this sort of adaptation a translation:

As with so many knee-jerk postmodernists, Bang’s poetics hinge on the belief that the “distinction between high culture and popular entertainment has all but ceased to exist.” So she’s free to throw in references to John Coltrane, “South Park,” Emily Dickinson, Andy Warhol, John Wayne Gacy, Stephen Colbert and Woody Allen, whenever it suits her purposes. Her Dante dwells in a pluralist’s paradise, even if he is in Hell.

But to say that contemporary culture no longer recognizes the difference between high and low art is not to say that there is no difference. It simply means that our culture has given up making the effort to sustain the difference. It is (again, ironically) a form of sour grapes.

Bang’s Inferno already has some corduroy-vested academics tugging on their beards with indignation and beetle-browed translators jabbing at their eyes with pencils.

Say what? As I said at the Book Haven, it’s maddening that in 2012, Vanity Fair can’t provide us with a simple link so we know which “corduroy-vested academics” are supposedly “tugging on their beards with indignation” and which “beetle-browed translators” are “jabbing at their eyes with pencils.” It’s summer, and Bang’s Inferno was out for a only week when the Vanity Fair blog post went live. Few academics, and certainly not the stereotypes who stumbled into Schappell’s imagination from early 1950s New England, have even read the book yet.

(The only time I can remember an angry academic reaction to a mass-market translation was the mid-1990s, when Anglo-Saxonists grumbled about Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf—not necessarily because Heaney took liberties, but because his version was set to replace a more literal translation in the Norton Anthology.)

Dante scholars are, in fact, the medievalists most accustomed to seeing “their” poet made over to reflect the look of the day. In a 1983 issue of Studies of Medievalism devoted to Dante in the modern world, editor Kathleen Verduin explains that in addition to being a rallying point for 19th-century Italian nationalism, Dante was big in France and hugely popular in Victorian England. According to Werner Friederich’s Dante’s Fame Abroad, 1350-1850, Dante’s ghost was suited to every English season:

Robert Browning admired Dante for “the endurance that stood him in such good stead during his happy life.” For Carlyle, Dante was “the hero as poet.” Yet Carlyle also saw in the Florentine a spirit certainly reminiscent of the Scotsman’s Calvinist ancestors . . . Macauley’s Dante, rather like himself, was a public figure, born in great times. [page references removed]

Verduin adds that many Americans saw Dante as a proto-Protestant. The Transcendentalists were beguiled by him; Hawthorne alluded to him; Melville found him “the infernal guide to ever-deepening realms of moral complexity”; Longfellow sought solace in translating him; Charles Eliot Norton founded an academic society around him; and James Russell Lowell considered the Divine Comedy a cathedral in poetic form.

In No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880-1920, T.J. Jackson Lears suggests that 19th-century America craved his moral certainty:

Nor was fascination with Dante confined to the Brahmin few. The poet was acclaimed and interpreted by critics in the established press, eulogized and imitated by dozens of magazine versifiers. The Dante vogue pointed not only to aestheticism or vaporous romanticism, but to widespread moral and religious concerns . . . By ignoring the scholastic superstructure of the Divine Comedy, commentators were able to join Dante with simpler medieval types. Like the saints and peasants, he became a prophet of spiritual certainty in an uncertain, excessively tolerant age.

At least three statues of the Big D here in Washington, the most prominent one in a park, attest to a literary wave that has since saturated the culture. Oh yes: You can pop “Dante’s Inferno Balls” candy while playing the Dante’s Inferno game for XBox or Playstation (with accompanying action figure). You can imagine the scent of Dante cigars, fondly recall the “Dante’s Inferno” ride at Coney Island, or show off your snazzy Dante earrings. You can also check out how science-fiction authors Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle Americanized Dante to make his Hell literally escapable.

“As a figure in the modern imagination, he has been all things to all men,” writes Kathleen Verduin, “enduring repeated reinterpretation according to the tastes and prejudice of the times; but he also unites us, commanding the common respect for the achievement of his art, and the endurance of his vision.” Whether ill-wrought or wonderful, Mary Jo Bang’s Inferno is the latest step in a dance between Dante and his American admirers. Contrary to Vanity Fair, scholars know the tune, too.