On a sunny September day in 1838, Frederick Douglass escaped slavery in Maryland to become a free man (and one of the most fascinating and indefatigable Americans of his time), so yesterday seemed like as good a day as any to visit Cedar Hill, the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site—and to seek medievalism in this most unlikely place.

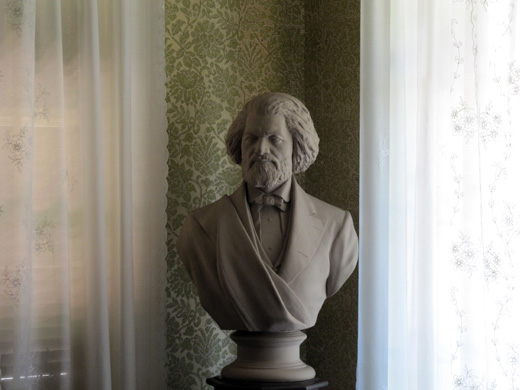

High atop a terraced hill in the Anacostia neighborhood of Southeast D.C., the house was Douglass’s home from 1877 until his death in 1895. The front—parlor, office, dining room—is furnished almost exactly as it was when Douglass was alive, and Cedar Hill is still an impressive home with a panoramic view of downtown Washington.

Many of the decorations in Cedar Hill are neoclassical doodads, but there’s a medievalist gleam or two in Douglass’s life, as long as you know where to look.

That’s the bedroom of Helen Pitts, Douglass’s longtime secretary and second wife. Their interracial marriage shocked her white abolitionist family and Douglass’s black children, but since I’m me and it’s 2012, I was more surprised by what I saw on the back wall: an engraving of Cologne Cathedral.

Although Douglass traveled in Europe, he doesn’t appear to have visited Germany, so the engraving was likely a gift from German writer and abolitionist Ottilie Assing. She taught Douglass German, spent 22 summers in his home, and apparently had a long affair with him. The presence of this print in the bedroom of the woman who won out over Assing for Douglass’s final affections is either a curatorial snafu or a memento of profound awkwardness.

More interesting is Frederick Douglass’s medievalist name.

Born a slave in Talbot County, Maryland, around 1818, young Fred was saddled with a moniker that suggested a grand, impossible destiny. “The name given me by my beloved mother,” he wrote, “was no less pretentious than “Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.'” In 1838, after being moved back and forth between the Eastern Shore of Maryland and downtown Baltimore, he made one heck of an escape: He disguised himself as a sailor, boarded a train, and journeyed from Wilmington, to Philadelphia, to New York City, and finally to New Bedford, Massachusetts.

In New Bedford, “initiated into the new life of freedom,” Frederick Bailey needed a safer surname. He found himself in the home of Nathan and Mary Johnson, a prosperous black couple who harbored escaped slaves. As he explained in 1855, taking their name was out of the question:

“Johnson” had been assumed by nearly every slave who had arrived in New Bedford from Maryland, and this, much to the annoyance of the original “Johnsons” (of whom there were many) in that place.

Down with the pop-culture trends of the day, Nathan Johnson suggested the name “Douglass”:

Mine host, unwilling to have another of his own name added to the community in this unauthorized way, after I spent a night and a day at his house, gave me my present name. He had been reading the “Lady of the Lake,” and was pleased to regard me as a suitable person to wear this, one of Scotland’s many famous names. Considering the noble hospitality and manly character of Nathan Johnson, I have felt that he, better than I, illustrated the virtues of the great Scottish chief. Sure I am, that had any slave-catcher entered his domicile, with a view to molest any one of his household, he would have shown himself like him of the “stalwart hand.”

Once absurdly popular and always unbearably long (and, despite its title, not Arthurian), The Lady of the Lake is an 1810 poem by Sir Walter Scott that tells the story of a rift between King James V of Scotland and James Douglas, his former mentor and protector, as tension mounts between the king and the Highland clans, roused to rebellion by Roderick Dhu.

I’ve never been able to get through the whole miserable poem, but the fact that Frederick Douglass is named after a fictionalized late-medieval earl is truly wonderful. It’s a testament to 19th-century America’s obsession with Scott’s chivalric adventures—and it’s a bit ironic.

Southern slaveowners hung on Sir Walter Scott’s every word, and they saw themselves as his chivalric heirs. Here’s Vernon Parrington in Main Currents in American Thought, Volume II:

The Lay of the Last Minstrel and The Lady of the Lake stirred Southern men to think of themselves as proud knights ready to do or die for some romantic ideal; and the long list of novels . . . seemed to reflect anew the old ideals of fine lords and fair ladies whom Southerners now set themselves to imitate.

“While the rest of America read Scott with enthusiasm,” writes Rollin Osterweis in Romanticism and Nationalism in the Old South, “the South assimilated his works into its very being.” Osterweis points out that plantation bookshelves were packed with Scott’s works; Southerners loved his terms “Southron” and “aristocratical” and ran with them; plantations took their names from his Waverley novels; and steamboats, barges, and stagecoaches in the back country of Louisiana, Tennessee, and beyond often bore names from his books.

In Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain even blames Scott for the American Civil War:

The South has not yet recovered from the debilitating influence of his books. Admiration of his fantastic heroes and their grotesque “chivalry” doings and romantic juvenilities still survives here, in an atmosphere in which is already perceptible the wholesome and practical nineteenth-century smell of cotton-factories and locomotives; and traces of its inflated language and other windy humbuggeries survive along with it.

It’s amusing to imagine the few Southerners who may have read Douglass’s autobiography sputtering over such blasphemous misuse of their dear Walter Scott.

Delightfully, the black American named for a medieval earl really did rally the Scots. In 1845, Douglass fled to Great Britain to avoid recapture and stayed until 1847. His speeches in Scotland echoed the concerns of British abolitionists that the Free Church of Scotland was funded by slave-holders and slave-traders. In My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass casts himself as the voice of the man on the Edinburgh street:

“SEND BACK THE MONEY!” stared at us from every street corner; “SEND BACK THE MONEY!” in large capitals, adorned the broad flags of the pavement; “SEND BACK THE MONEY!” was the chorus of the popular street songs; “SEND BACK THE MONEY!” was the heading of leading editorials in the daily newspapers.

The modern Douglass did not prevail:

The deed was done, however; the pillars of the church—the proud, Free Church of Scotland—were committed and the humility of repentance was absent. The Free Church held on to the blood-stained money, and continued to justify itself in its position—and of course to apologize for slavery—and does so till this day. She lost a glorious opportunity for giving her voice, her vote, and her example to the cause of humanity; and to-day she is staggering under the curse of the enslaved, whose blood is in her skirts. The people of Scotland are, to this day, deeply grieved at the course pursued by the Free Church, and would hail, as a relief from a deep and blighting shame, the “sending back the money” to the slaveholders from whom it was gathered.

In his 1899 bio of Douglass, Charles Chesnutt notes that “[i]n Scotland they called him the ‘black Douglass,’ after his prototype in The Lady of the Lake, because of his fìre and vigor.” Chesnutt knew when to strum that mythic chord:

[H]e fell in with the suggestion of his host, who had been reading Scott’s Lady of the Lake, and traced an analogy between the runaway slave and the fugitive chieftain, that the new freeman should call himself Douglass, after the noble Scot of that name. The choice proved not inappropriate, for this modern Douglass fought as valiantly in his own cause and with his own weapons as ever any Douglass fought with flashing steel in border foray.

Although Frederick Douglass was a passionate man, I was sure he was immune to the charms of the phony, romanticized Middle Ages that gave him his name. Nope! According to the National Park Service (PDF here), Douglass owned 18 volumes of Sir Walter Scott.

In his writings and speeches, Douglass had more to say about Dred Scott than Walter Scott, so I’m hesitant to dub him a medievalist, but it says something about America’s weird medievalist undercurrents that they were too strong to escape his notice. They didn’t ebb: In an 1895 eulogy, one poet was quick to cast Douglass in medieval terms. “A hush is over all the teeming lists,” sang Paul Laurence Dunbar, making him the knight the man who named him hoped he’d be: “He died in action with his armor on.”

Your mention of Paul Laurence Dunbar at the end reminds me of another great poet named Dunbar: William Dunbar, who was active in the late 15th C and closely associated with the court of James V’s father, James IV. My old supervisor at St Andrews was disappointed to learn that Dunbar HS in Washington (home of the Poets) was not named for William. Apparently PLD is as unknown in Scotland as William is to most Americans.

Maryland history is full of odd little medieval kinks. The most prominent is the feudal nature of land ownership during the colonial period. There are actually records of escheats — escheats! — in the Maryland State Archives.

LikeLike

Funny you should mention Maryland escheats! I’ve been reading up on a few aspects of Maryland medievalism for a future post. Stay tuned…

LikeLike