Civitas amoena, Wynlicburh—whatever faux-archaic nickname Baltimore deserves, the city has much of the medieval about it. The Walters Art Museum has a wide-ranging medieval collection, medieval Poles appear on an anti-Stalinist monument, countless neo-Gothic churches linger in varying states of neglect, and in Druid Hill Park, there’s a statue of a Scottish superstar.

That’s why it’s easy to miss the obvious example of Charm City’s ersatz medievalia: the Bromo-Seltzer Tower, a major downtown landmark. When he leads tours, the current manager of the place calls it “the world’s only novelty clock tower built to advertise a tranquilizer-laden hangover cure.” I don’t doubt him—but the Bromo-Seltzer Tower is also Bawlmer’s monument to America’s love for medieval-ish architectural follies.

Built in 1911, the Bromo-Seltzer Tower originally had a factory at its base. Now there’s a parking deck and a fire house, while the tower provides studio space for artists who invite the public to peek inside on Saturdays. Bromo-Seltzer founder “Captain” Isaac Emerson, a flamboyant and famously insufferable businessman, built the tower to advertise his wares: Until 1936, the tower supported a ludicrously huge and glowing blue bottle with a crown on top.

Emerson’s aesthetic was passing strange. A few years earlier in Florence, he’d seen the Palazzo Vecchio and apparently thought to himself, “I want one.” Architect Joseph Sperry, known for light eclecticism, did what he could to bring 13th-century Tuscany to the corner of Lombard and Eutaw Streets.

(Left: the Palazzo Vecchio, from Wikimedia Commons. Right: a photo I took this weekend.)

The Bromo-Seltzer Tower is clearly more of an omaggio to the Palazzo Vecchio than an exact replica, but it is closer to its source than the squat “Palace of Florence” Apartments built 13 years later in Tampa, Florida.

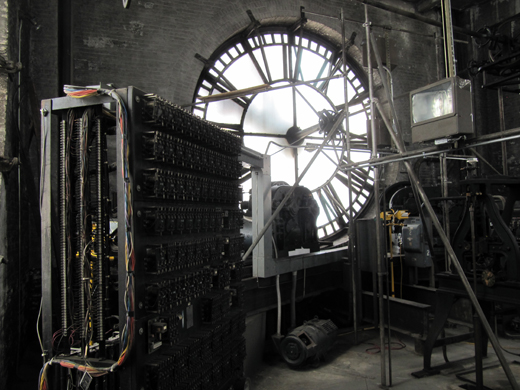

However, stepping inside on a summer day leads you not to medieval Italy, but back to the sweltering days of early 20th-century office life, while the timeworn interior of the clock tower looks like a cross between a Coen Brothers movie set and a vintage superhero lair. (I’ve always remembered the tower for its role as a sniper’s nest on a 1996 episode of “Homicide: Life on the Street.”)

When the Bromo-Seltzer Tower went up in 1911, H.L. Mencken was the first to hate it. “All Baltimoreans may be divided into two classes,” he wrote. “[T]hose who think that the Emerson Tower is beautiful, and those who know better.” Like Mark Twain, Mencken couldn’t see that something deeper was going on with America’s love of pseudo-medieval stuff—that we used this kind of architecture in our churches, colleges, prep schools, factories, and office buildings to brag, to be trendy, or to claim some link to the past.

Nostalgia later makes some aesthetics irresistible. Almost every brick or mechanism inside the clock tower is black, white, or gray, which makes the room seem art-directed and hyper-real. Like the tower itself, the huge, clattering, circa-1964 computer that still runs two tiny, nerve-wracking elevators is now a fascinating relic rather than an eyesore.

Facilities manager Joe Wall, a Baltimore native who’s full of great stories, told me that at some point, repair work on the tower’s rooftop cupola-thingie meant that someone added two levels of castellated ramparts that clearly weren’t there in 1911. As a result, the Bromo-Seltzer Tower is now less Italianate, more generically medieval, and a bit more like the palace-fortress that inspired it. No longer a monument to crass commercialism, it defends the notion that indulgent medievalism ages well—after the inevitable hangover.

Drat, I wish the blue bottle was still there! Hilarious. Love the name of the tower…

LikeLike

i was not old enough to remember any of this i was born in 1971 but am a serious esssex maryland history buff anything i can get my hands on would be greatly appreciated weather that means i have it for real in my hands or see it in your comments or your pictures thanx again this is some awesome information for those of us who didnt live it i think and maybe even good enough for the older crowds to look back on

LikeLike

Technically, the Emerson Tower is an example of Renaissance revival architecture. This style came into fashion a little after the Gothic (Medieval) revival fell out of favor. So, the Tower should be considered “pseudo-Renaissance” rather than “pseudo-Medieval.”

LikeLike