For most of us, inspiration is a whisper, slight and private—so I love when eccentrics with outsized visions find huge ways to share their obsessions with us. A few weeks ago, I discovered one such site in Pennsylvania; it’s literally monumental.

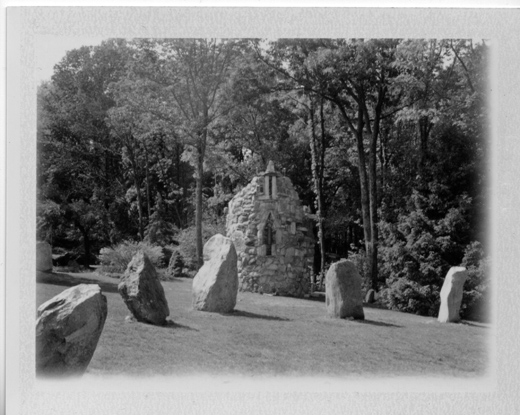

Along an uphill webwork of winding roads, you’ll find a stone circle and dozens of other menhirs, dolmens, and megaliths strewn across 17 acres of groves and paths. The park is a refuge for pilgrims to rest, roam, ponder, and (in my case) take snapshots with antique Polaroids, most of them as murky as whatever moved the soul in a nearby house to haul these huge stones into place.

Celtic nostalgia is cousin to medievalism; a kindred impulse shaped them both. As far back as the English constitutional debates of the 17th and 18th centuries—was the Norman Conquest legit?—the druids were in play. Supporters of Parliament wanted to show continuity from the Germanic Saxons, who were seen as practicing a sort of primitive democracy temporarily kiboshed in 1066; monarchists wanted to override their claims with a more ancient political inheritance from pre-Germanic Celtic Britons. With the druids in mind, boosters of the British Empire also saw proof that savage people could be conquered, colonized, and redeemed—although the Welsh and the Cornish soon showed the power of druids as defiant patriotic symbols instead.

In the 1760s, the discovery of an epic cycle by the ancient bard Ossian famously beguiled readers on both sides of the Atlantic; it was a fake by a Scottish poet, but the Celts of romance conquered and thrived. Students of medieval lit still read Arthurian legend in the wake of 20th-century scholars like Roger Loomis, who never failed to discern minute echoes of Celtic ritual on every interminable page. Since the 1980s, the comically prolific John and Caitlin Matthews have cranked out piles of books that nourished a neo-druid British counterculture with growing political heft.

In the United States, popular Celticism has been domesticated; as with medievalism, less is at stake, so we make it our own. You’ll find it in neopagan spirituality and in the nostalgia of Scottish and Irish ancestral pride—and, it seems, in the shady groves of eastern Pennsylvania.

As I rested under a wooden awning, a golf cart came zipping down from the large modern house overlooking the stones. Behind the wheel was Bill, who founded the park in the 1970s. We talked about the inevitable breakdown of human institutions, the fleeting nature of the physical world, and the holy mischief of making places for future myth.

According to his book (for sale on the honor system in a nearby shed), Bill was a Presbyterian minister, but a series of dreams and mystical experiences on the Scottish island of Iona apparently turned him into a universalist. Since then, he’s busily created what is, at the very least, an ecumenical work of visionary landscape art. In addition to the main stone circle, his site includes a dolmen devoted to Thor, a path through a “faerie ring,” sacred male and female groves, a quirky bell tower inspired by an Ionian saint who was buried alive, stones for St. David and St. Brigid, and a lovely chapel to St. Columba, the Irishman who spread Christianity in Scotland.

Some years ago, the Presbyterian church on Simpson Ferry Road in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, would kick off it Easter Sunday service with a procession led by a bagpiper. As far as I know, most of Highland clans leaned toward Anglicanism, and the heart of the Presbyterian Church was in the Lowlands, where kilts and bagpipes were anything but welcome. The town names around there–Londonderry, Antrim, etc.– indicate a stop in Ulster, which again was nothing to encourage a liking for the Celtic survivals. But American life does not encourage nice distinctions, does it?

I was interested to see Nabokov say good things about Ossian in the notes or preface to his translation of The Song of Prince Igor.

LikeLike

He built a folly! And a very tasteful one too. Since I crossed the Atlantic to learn cuneiform, I can hardly object to other people’s passionate eccentricity.

LikeLike

I really admire people who pursue things that are viewed by the modern mind to be “worthless.” I used to take great pride in telling people that I was an English major who (at the time) had no plans of becoming a teacher; I was reading books to read books. I took classes on Old English mostly because I would never be able to use it in the “real world.” I took bitter satisfaction when I went to my local library and, when looking for an Old English dictionary, could only find a book on Old English sheep dogs. We all could use our own “folly.” It’s a kind of transcendence. Gods bless him, I say.

LikeLike

George: Thanks for the reminiscence! Indeed, there’s nothing in Bill’s book to indicate how he came to own property in that area of Pennsylvania as an adult. As for a lack of nice distinctions, the visitors’ lounge—basically a shed with water, coffee, tea, and pamphlets—houses a small library that focuses on three subjects: Christianity, New Age spirituality, and geology.

Sean: No objections here either. I don’t think Americans are quite as familiar with the less pejorative British use of the term “folly”; it’s a usage I’m happy to help propagate.

Chris: Oh, yes—when I look at my own creative projects, I see certain but small-scale folly. I’m good with it…although it does make me wonder what I’d be up to if I found myself in possession of an unseemly pile of cash.

LikeLike

I think I learned of folly in the sense of “purpose-built ruin” or “magnificent but eccentric project” from some children’s books about teenagers boating on a British river and helping to excavate Roman watchtowers. That was long ago, but once upon a time Canadian libraries bought a fair number of British books for children.

LikeLike

I don’t think I learned it until I was in my late twenties, when I wrote a newspaper article about Portmeirion Village in Wales. Needless to say, that place planted it firmly in my vocabulary…

LikeLike