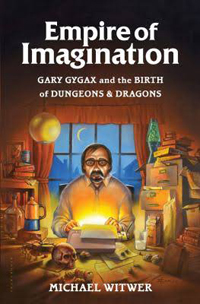

When Gary Gygax died in 2008, I called him “one of the most influential medievalists of the latter half of the 20th century.” I still think that’s true: without the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, medieval-ish fantasy and gaming wouldn’t have blossomed into mainstream obsessions. Gygax lashed together the conceptual trellis for both, but exactly how he did it was a mystery to me. As a kid, I knew him only as a distant sage who beguiled the rest of us with eldritch parlance and baroque prose, but thanks to Michael Witwer’s Empire of Imagination: Gary Gygax and the Birth of Dungeons and Dragons, I can at least glimpse the outlines of this legendary tabletop adventurer—but not much more. As it turns out, his was a far more labyrinthine mind than even his biographer anticipated.

When Gary Gygax died in 2008, I called him “one of the most influential medievalists of the latter half of the 20th century.” I still think that’s true: without the co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons, medieval-ish fantasy and gaming wouldn’t have blossomed into mainstream obsessions. Gygax lashed together the conceptual trellis for both, but exactly how he did it was a mystery to me. As a kid, I knew him only as a distant sage who beguiled the rest of us with eldritch parlance and baroque prose, but thanks to Michael Witwer’s Empire of Imagination: Gary Gygax and the Birth of Dungeons and Dragons, I can at least glimpse the outlines of this legendary tabletop adventurer—but not much more. As it turns out, his was a far more labyrinthine mind than even his biographer anticipated.

At first, E. Gary Gygax of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, was the bright, nerdy child I knew he would be: a lover of strategy games, especially chess; a fan of Robert E. Howard’s “Conan” stories; and a dungeon-delver who led his friends through an abandoned sanatorium in the dark of night. Witwer presents him as a smart, undisciplined underachiever who dabbled in a little of everything, from fishing to cobbling, but whose passion for late-night wargames in his friends’ basements was so all-consuming that his wife was convinced he was cheating on her. Empire of Imagination explains how Gygax and dozens of like-minded misfits found each other, how they elevated tabletop wargames into guided improv with dice, and how their hobby became a commercial phenomenon that unfurled its leathery wings and abandoned them all. It’s a straightforward story, but it probably shouldn’t be; several cryptic anecdotes hint that the journey was circuitous and strange.

Witwer mentions that in the late 1950s, after dropping out of high school but before getting married, Gygax served briefly in the Marines. But for how long, and in what capacity? When the subject is an ardent wargamer, these details matter. In one of several fictionalized inner monologues, Witwer imagines that Gygax hated boot camp and was happy to be discharged for health reasons—but did Gygax himself discuss the experience? What did he learn from it? How did he see the role of war in human affairs? Empire of Imagination doesn’t answer these questions—and it raises too many more.

Early on, Gygax supported his family as an insurance underwriter, but Witwer suggests that the main influence of this job on his game-writing hobby was the convenience of the office typewriter. I don’t doubt that the typewriter was handy—but isn’t it noteworthy that a guy who spent his days poring over actuarial data would go on to craft a game around pages and pages of probability-based tables? I wish Witwer had drawn this connection; there’s meaning in it. It’s charming that one of the quirkiest countercultural pastimes, now an endless wellspring of self-expression and creativity, has roots in a field that most people find utterly deadening.

The biggest surprise in Empire of Imagination pops up halfway through the book, when Witwer writes about conflicts between the Gygaxes and their children in the late 1970s:

Another point of dissension between Gary and his son was that Ernie had drifted away from his parents’ faith, the Jehovah’s Witnesses. In times past, Gary had made attempts to pull away from gaming in favor of devoting more time to his faith, but such efforts were always short-lived. And while not “devout” by Jehovah’s Witness standards, Gary and Mary Jo had maintained the religious affiliation and expected their children to follow suit.

Wait—what? The Prime Mover of geekdom and godfather of role-playing games, dogged by accusations of promoting demonology and witchcraft, was a Jehovah’s Witness? That’s a heck of a revelation not to poke with a stick. Was he born into the religion? Did he adopt it as an adult? Witwer doesn’t say. Twenty pages later, Gygax and his wife break from their church over gaming, drinking, and smoking, and that’s that. But how can it be that the co-creator of a game steeped in magic, mysticism, polytheism, and violence was active in a faith most of us think of as uncompromising and austere? Are there traces of the religion in the design of D&D, and if so, what are they?

It’s clear from Witwer’s lengthy sketch that Gygax demands a thorough intellectual biography. He was a complex autodidact whose inner life wasn’t easy to categorize or explain, the product of an unrepeatable alchemy of place, time, and personality—but unless someone can conjure a compilation of interviews, letters, and reminiscences by family and friends, Empire of Imagination may be the best glimpse of his life we’re going to get. It’s engaging and earnest; it just doesn’t feel done.

Fortunately, Empire of Imagination is also the story of a business—a lurid cautionary tale that Witwer relates with enthusiasm. In 1973, when no gaming publishers wanted the original Dungeons & Dragons manuscript, Gygax and two fellow gamers incorporated TSR—”Tactical Studies Rules”—and published it themselves. Like any empire, TSR was soon rife with enmity, backstabbing, and strife. The untimely death of one of the founders in 1975 reverberated for years: An investor who bought his widow’s one-third share would introduce a family of executives who, as Witwer tells it, despised everything about the gaming world but its potential revenues. By the early ’80s, their preposterous excess was worthy of a Simpsons episode: In Hollywood, Gary Gygax was blowing millions on D&D-based entertainment prospects, leasing King Vidor’s mansion, and snorting cocaine in a private booth at the Playboy Club, while back in Wisconsin, the colleagues who despised him were funding shipwreck excavations and investing in real estate on the Isle of Man. When Gygax recaptures the company in a startling coup and writes a book that restores solvency to the land, the tale takes a hopeful turn—until one Hollywood hanger-on proves to be an enemy in disguise…

Fortunately, Empire of Imagination is also the story of a business—a lurid cautionary tale that Witwer relates with enthusiasm. In 1973, when no gaming publishers wanted the original Dungeons & Dragons manuscript, Gygax and two fellow gamers incorporated TSR—”Tactical Studies Rules”—and published it themselves. Like any empire, TSR was soon rife with enmity, backstabbing, and strife. The untimely death of one of the founders in 1975 reverberated for years: An investor who bought his widow’s one-third share would introduce a family of executives who, as Witwer tells it, despised everything about the gaming world but its potential revenues. By the early ’80s, their preposterous excess was worthy of a Simpsons episode: In Hollywood, Gary Gygax was blowing millions on D&D-based entertainment prospects, leasing King Vidor’s mansion, and snorting cocaine in a private booth at the Playboy Club, while back in Wisconsin, the colleagues who despised him were funding shipwreck excavations and investing in real estate on the Isle of Man. When Gygax recaptures the company in a startling coup and writes a book that restores solvency to the land, the tale takes a hopeful turn—until one Hollywood hanger-on proves to be an enemy in disguise…

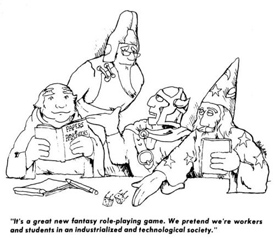

I like to believe that Gygax saw himself as a hero embroiled in a magnificent story of palace intrigue, but Empire of Imagination documents a vulgar reality: the first time anyone looked at the burgeoning geek subculture and saw the cash cow it could someday become. As such, it’s a parable of hubris and greed far different from the stories that sensitive outsiders once told about themselves. I’m not sure young people today can envision what it was like when this stuff was so far outside the mainstream that it was socially poisonous, when it spread like secret lore among strange boys who sought refuge and fellowship in its small, exciting world. We now know that the bookish misfits of yesteryear could be just as venal as anyone else, but it takes imagination to remember the daydreams and desperate optimism that drove them to find each other. Gary Gygax and D&D co-creator Dave Arneson collaborated by mail at a time when even long-distance phone calls between Wisconsin and Minnesota were prohibitively expensive, and the first big gaming convention Gygax organized in 1968 had fewer than a hundred attendees. No wonder their hopes found expression in medievalist fantasy: finding other kids who shared their interests was a genuine, ongoing quest.

The world has changed. Big companies have succeeded where TSR failed: they’ve learned to exploit the public’s appetite for fantasy through movies and literally endless video-game franchises, while fan artists and makers of memes do much of their promotion for free. Even most Renaissance festivals are now run by large entertainment corporations. Who’s doing the imagining for whom? Although Witwer is right to see Gary Gygax as a founding father of 21st-century popular culture, Empire of Imagination reminded me of a time when weird young people could be fantasists rather than customers first. For all the adventures awaiting them now, there’s one that kids can no longer experience, at least not through games: the thrill of helping map out something new.

That is an interesting take.

I would say that one of the startling things about the roleplaying-game industry is the way that it has =resisted= commercialization and assimilation by large companies. There just does not seem to be enough money in it, or a way to package a substitute for hard creative work by the players and GM. In the end, people who wanted to make serious money had to move into other media like computer games and TV and appeal to tabletop roleplaying as part of a broad geek culture, along with the public-domain staples (Sherlock Holmes, the Cthulu Mythos) and the properties owned by big companies (Star Trek, the Marvel universe).

Similarly, part of the reason that roleplaying gaming has proved so hard to commercialize is that so many fans are eager to write material themselves! Far from being passive recipients of culture distributed from a few rich centres, enthusiastic roleplayers seem to be busy posting their session notes online and marketing their Patreon accounts, Kickstarters, and webcomics (just like the serious Trekkies are writing fanfic and debating crossover battles and assembling cosplay kits, and not just buying DVDs and autographs). This explosion of small business run by creative people distributing things over the Internet strikes me as something new.

LikeLike

Sean, those are great points. I certainly didn’t mean to insult gamers who’ve been busily doing their own thing under the commercial radar for decades. I applaud them! They’re just totally invisible to people like me who aren’t really part of that scene anymore. (I certainly see it in kids who are going gung-ho with, say, Minecraft without having spent more than a few dollars.) I suppose what bugs me is that the DIY ethos didn’t go mainstream when the rest of this stuff did, and I’m questioning whether the overall popular culture has genuinely changed in substance or merely in appearance. Sorry; I should have been more clear about that.

As someone who’s increasingly looking for ways to support small but ambitious creative projects–art, books, games–that don’t rely on megacorporations, I’ll confess that I’m often put off by the extent to which mainstream geek culture defers to the authority of massive corporate franchises. When Star Wars fans struggle to rectify plot discrepancies like they’re at the Jesus Seminar and fret over canonicity questions like they’re parsing the Talmud, it drives me nuts. Who cares? Take the bits you love and run with them! Enjoy them even if some jerk at Disney has declared them apocryphal. (Of course, I’ll concede that for some people, playing at pseudo-scriptural scholarship is itself fun…)

I recently returned to the gaming table for the first time in more than 25 years when the son of an old friend decided he wanted to gather his friends and learn to play D&D. We’re living examples of your point about how hard it is to monetize this stuff: we’re using tattered books that haven’t put a copper piece in anyone’s pocket for more than 30 years…

LikeLike

OK, I think I understand more. “Minecraft” is a good example of computer gamer culture returning to the old ethos of everyone creating their toys together (although there have always been people modding commercial computer games or repurposing the engines).

The “cheapskkate” aspect of roleplaying-games culture might be another thing which a sensitive biographer could link its origins in the small-town Midwest. I have a vague impression that the Gygax family is trying to protect the memory of their late =pater famillias=, and that he kept talking about those ten years before he lost control of TSR for good, so it may not have been any easier for Witwer to unpick the truth from the legend than it was for Polybius …

LikeLike

Two of my children did a lot of RPG when growing up, connecting to people around the world on line… They still are linked to some of those people today. And all three played some D&D with their father; they were big board game players for a while.

Fascinating post. I still love homemade entertainment (I guess writing books is a sort, too.)

LikeLike

Sean: Sorry to have missed your comment for so long! That small-town Midwestern “cheapskate” angle is one I’d never considered—interesting notion. I hope Gygax’s kids aren’t trying to downplay certain aspects of his life or personality, because I think his name is so beloved among gamers of a certain age that even the revelation that he was a Jehovah’s Witness isn’t likely to change that. My sense is that people want to know who he really was, warts and all, beyond the public persona whose books and pronouncements they read. I find that his foibles make him far more interesting.

Marly: Yeah, the “homemade entertainment” aspect of things is great. Sean is right to point out places where it’s still happening, and there’s an interesting emphasis on “makers” out there right now, but I wish it were more a somewhat more prominent phenomenon in entertainment, because small, independent writers, artists, etc., are definitely feeling the pinch. They always have, of course, but it would be nice if more people were taking a chance on a book from a small press, a local artist or artisan, or what have you. SF and fantasy fans have become really enthusiastic in the past couple decades, but the older I get, the odder it is for me to see people dressing up not as characters of their own creation, but as corporate-owned intellectual properties…

LikeLike