“The Green Knight is everything you love about King Arthur, but with a twist.” That’s the tag line Comcast is using to advertise streaming rentals of writer-director David Lowery’s visually sumptuous new movie. The angle surprised me: I didn’t know Arthuriana still sells. My sense was that the Arthurian boom peaked in the late ’90s with scores of fantasy novels and a few Hollywood movies, and I don’t think the streaming-video and Marvel Cinematic Universe generation has any particular love for the Matter of Britain.

Yet Lowery is undeterred, cheekily billing The Green Knight in its opening credits as “a filmed adaptation of the chivalric romance by Anonymous.” Of course, it’s not really an adaptation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The court is never identified as Arthur’s Camelot, Gawain has a girlfriend, and the young squire takes up the Green Knight’s challenge out of a mixture of gratitude to his royal uncle and a yearning to star in a tale of his own. “Do not waste this,” warns the king, who doesn’t see the need to decide if the Green Knight’s wager is a trivial Yuletide game or an opportunity for greatness. Scenes, characters, and motifs from the medieval poem make cameos, but once Gawain sets off on his quest, even a reader familiar with the source material is well off the edges of the map.

The film provides signposts to amuse and misdirect the medievalist. To my amazement, a battlefield scavenger refers to a line from the ninth-century Welsh chronicler Nennius. At one point, Gawain reads “When the nyhtegale singes” from the 14th-century Harley manuscript in the British Library. The artwork showing the changing seasons behind a children’s puppet show is, I think, from a late medieval Book of Hours. I’m sure a ton of other visual references flew right past me. The Green Knight is a determinedly unfunny movie, but the art and design team clearly reveled in creating a setting that feels like an afternoon at the Cloisters, where one medieval century blurs lazily into the next.

Even without these gratuitous flourishes, the world of Lowery’s medieval fantasy would feel convincing. The king, never explicitly acknowledged to be Arthur, looks plausibly weak, aged, a tad unhinged. The queen, gray and mirthless, wears a dress that appears to be decorated with hundreds of medieval pilgrimage badges. Women dye and sew, bishops pray, woodsmen fell forests, and shepherds tend their flocks, and there’s a magical British bleakness to the land itself that suggests the hardness of life. The opening scene, a stationary shot of animals milling about in front of a shed on Christmas morning while a house burns down in the background, nicely suggests the natural world’s indifference to man. When Gawain sets off on his quest, one somber, uncomfortably long shot follows him away from the castle and through a heath, perfectly capturing the quiet uncertainty of preparing to travel alone.

If only The Green Knight had eloquent, poetic dialogue to match these rich visuals. Here’s a speech from the king early in the film:

I look out upon my friends here today and I see songs no muse could ever sing, or dream of. But I turn to thee and I see what? I recognize but I do not know thee. I say this not in reproach but in regret that I have never asked you to sit at my side before this day, or upon my knee when thy [sic] was newborn. But now it is Christmas, and I wish to build bridges.

For a film obsessed with lovely visual and cultural touches, The Green Knight shows no awareness of how speech in a pseudo-medieval fantasy world ought to sound. The mixture of “thee” with “you,” the ignorance of the simple “thou,” and the misuse of “thy” are constant, baffling oversights across the whole movie. At one point, the king asks Gawain, “What have thee?” When a medieval British saint turns up, even she doesn’t understand medieval or early modern pronouns. Some fine actors in this movie end up sounding like eight-graders at their first Renaissance fair, as if they’ve never heard a word of Shakespeare. The 1984 Miles O’Keeffe-Sean Connery fantasy movie Sword of the Valiant, also based on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, flies hilariously off the rails after its first fifteen minutes, but at least its script gives good actors lines like “a sword is three feet of tempered steel, with death dancing on every inch and hanging like a dark star on the very point,” or “the old year limps to its grave, ashamed.” There’s a weird lack of wit and precision to the dialogue in The Green Knight, so strange for a movie that’s based on a gorgeous poem, uses quirky on-screen titles, draws directly from medieval chronicles and saints’ lives, and shows characters reading and adoring books.

Although I don’t plan to check, I’m guessing the Internet saw some ugly arguments in recent weeks about the decision to cast an Anglo-Indian actor to play Gawain. Who cares? Dev Patel is a compelling actor with a strong aura of vulnerability, and he’s a great Gawain in a movie where everyone is equally well-cast. Besides, the poem that inspired this film isn’t a historical document; it’s a weird, brilliant, stylized fantasy. Filmmaker David Lowery gets that, which is maybe why The Green Knight felt to me like a sincere 1980s American fantasy flick mated with the cinematographic resources of a humorless European art-house film. That’s not necessarily a deadly combination. Gawain’s episodic quest is packed with eerie images, and as a viewer you can write them off as random or try to find symbolic coherence in them as you please. In that sense, The Green Knight captures some of the unsettling weirdness of reading a medieval romance.

No one would ever take The Green Knight as an attempt at a faithful adaptation, and a generation of graduate students will likely pad their CVs with tiresome conference presentations about its loose relation to its medieval source. The film itself winks a few times in recognition of its creative deviations, first in a quick montage of the title in various typefaces, reflecting different editions and translations, and then in a character who admits to seeing “room for improvement” in certain stories whenever she copies old manuscripts. For me the question is not whether this movie is good or bad based on its level of faithfulness to its medieval source, but whether the filmmaker used his sources as a productive jumping-off point to create a new and interesting work of art.

I don’t think he did. The film puts forward some thoughts about following a code of honor to its thankless end, but the alternative, living a lie, leads to no less unhappiness—a much bleaker conclusion than the original poem’s gracious assessment of flawed human nature, where a hard tale’s leavened by lightness of heart. And so help me, the last fifteen minutes of The Green Knight recall one of the more unsuccessful efforts of Martin Scorsese, and it’s not remade more coherently here. The way Lowery has rooted through history, artwork, and scholarly scraps is an impressive act of medievalism, but his pastiche doesn’t say anything clear about the present or the past.

But maybe it will. Many “medieval” movies—I’m thinking of John Boorman’s Excalibur or that odd 2007 motion-capture Beowulf—need time to age, to cure or curdle into artifacts of their time. The Green Knight might someday be better in hindsight, when it’s influenced a generation of artists, aspiring historians, and would-be scholars who will recall how it felt in their bones to live through a pandemic, social unrest, and a disastrous military withdrawal. By then, this medieval dream and our current age may feel equally distant to them, and the despair in this movie will echo an overcome past.

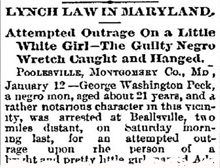

A knight sliced in half like a sesame bagel, a saint tossed down a hillside in a barrel lined with nails—pain is an ageless wellspring of humor, but we were too weirdly willing to laugh. As graduate students, we were honing our sense of which aspects of the Middle Ages were born of certain eras and places and which others were timelessly human. Yet something about the classroom made the medieval world harder for me to imagine. The line of scholars whose work helped us understand the past in the first place also stood in the way of a gut-level sense of real people’s lives. Then the violence was never real, only a source of other people’s pictures or words, like an idealized painting or flippant cartoon.

A knight sliced in half like a sesame bagel, a saint tossed down a hillside in a barrel lined with nails—pain is an ageless wellspring of humor, but we were too weirdly willing to laugh. As graduate students, we were honing our sense of which aspects of the Middle Ages were born of certain eras and places and which others were timelessly human. Yet something about the classroom made the medieval world harder for me to imagine. The line of scholars whose work helped us understand the past in the first place also stood in the way of a gut-level sense of real people’s lives. Then the violence was never real, only a source of other people’s pictures or words, like an idealized painting or flippant cartoon. Last month, our town

Last month, our town