[This is the fourth of four blog posts focusing on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s medieval-themed stories. The first post can be found here, the second can be found here, and the third one is here. If it matters to you, please be aware that these posts about obscure, 80-year-old stories are pock-marked with spoilers.]

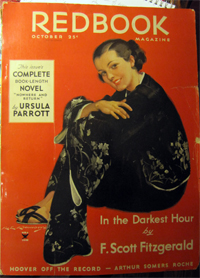

Six years passed between the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third “Philippe” story and the fourth and final entry in the series. By the time “Gods of Darkness” debuted in the November 1941 issue of Redbook―which hailed the seven-page sketch as its “novelette of the month”―Fitzgerald had been dead for almost a year. According to scholar Janet Lewis, Redbook had been the only magazine willing to print the stories, and I’m guessing they ran this final installment out of some combination of nostalgic tribute and contractual obligation.

Six years passed between the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third “Philippe” story and the fourth and final entry in the series. By the time “Gods of Darkness” debuted in the November 1941 issue of Redbook―which hailed the seven-page sketch as its “novelette of the month”―Fitzgerald had been dead for almost a year. According to scholar Janet Lewis, Redbook had been the only magazine willing to print the stories, and I’m guessing they ran this final installment out of some combination of nostalgic tribute and contractual obligation.

A reader who’s made it this far into the Philippe stories knows what’s coming. There’s the ninth-century warlord inspired by Ernest Hemingway, the anachronistic 1930s gangster slang, the dull prose that always tells and never shows, and a boyish obsession with the building and maintenance of forts.

I’m not kidding about the forts:

Half a dozen horsemen, irregularly strung out, began feeling their way down the forty-five-degree angle of the slag-and-sand slope.

“That’s my fort,” Philippe said. “You like it?”

[ . . . ]

In sight of the castle he had made on the hilltop, he drew rein for a moment, to reward his own work admiringly. New wooden structure was risen to replace the first crude one, destroyed by the King’s incendiaries. This one, like the first, was of logs, but it was taller, more elaborate within and without. His current problem was to try to make a moat by letting in the Loire; but having no engineering education, and commanding no one who understood the process, the venture had so far been confined to digging fine-looking ditches and then seeing them either washed quickly away, or else coquettishly avoided by the choosy water of the river.

“It’s good, though, isn’t it?” he demanded of Griselda. “We’ve got a house; we’ve got quarters for the boys; we’ve got pasture for the animals―and we’re beginning to have a little city down here around the foot of the hill. There’s ten, twelve houses….”

If Fitzgerald had spent even half that much time exploring the conflicting subtleties of the medieval mind, the Philippe stories might feel inhabited by humans. Instead, the banter between Philippe and Griselda is as flat as a scene from a 1930s “B” movie:

Griselda, fatigued, dismounted in the pasture halfway up. Pale and lovely, she sat in the last lush grass of October.

“I love you, Philippe,” she said as he dismounted beside her. “Oh, I don’t mean that―I was just thinking: can’t I love you sometimes when you don’t expect it?”

The pale wonder of her skin was a texture so like death that for a moment Philippe hardly knew what he held in his suddenly gentle arms. Only when a bearer of water had come and returned, did Griselda move and whisper: “I know I’m difficult, Philippe; but you’re so difficult, and I never had anything like this happen to me before.”

“Cheer up―you’re all right,” said Philippe. He had a dread of anything happening to her delicate health.

Despite his oppressive deadpan, Fitzgerald tries here and there to be playful, to no real end. “In less time than it has taken to describe Philippe’s bodyguard, he met the approaching party,” he writes at one point, a wink from a narrator who rarely steps forward with thoughts. I’m not the first reader to wish that the Philippe stories were filtered through the eyes of an observer, a ninth-century Nick Carraway who could have given Fitzgerald’s version of the Middle Ages a solid sense of place.

Despite his oppressive deadpan, Fitzgerald tries here and there to be playful, to no real end. “In less time than it has taken to describe Philippe’s bodyguard, he met the approaching party,” he writes at one point, a wink from a narrator who rarely steps forward with thoughts. I’m not the first reader to wish that the Philippe stories were filtered through the eyes of an observer, a ninth-century Nick Carraway who could have given Fitzgerald’s version of the Middle Ages a solid sense of place.

Fortunately, “Gods of Darkness” delivers a plot twist that at least deserves points for novelty. During the months Fitzgerald spent immersed in scholarly books and working out historical timelines, he was beguiled by Margaret Murray’s 1921 book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. As Philippe starts to become a competent ruler of his ancestral lands, he realizes that his girlfriend and his henchman both speak a strange language and hold secret influence over the locals. His military prowess and burgeoning administrative skills will mean nothing unless he allies himself with an unpredictable force, the local witch cult:

“I haven’t got any conscience except for my country, and for those who live in it. All right―I’ll use this cult―and maybe burn in hell forever after…But maybe Almighty Providence will understand.” He looked toward the swift flow of the Loire. “Maybe He built a castle once. Maybe He knows.”

And then defiantly:

“But if these witches know better, then I’ll be one of them!”

If Fitzgerald had stopped at “Maybe He knows,” then Philippe might have become a broken-down idealist worthy of noir. Instead, the big, dumb warlord bellows his intentions, drowning out a moment when Fitzgerald should have respected his readers’ capacity for inference. We’re detached from the fate of a character we’ve barely been persuaded to care about, with none of the gut-punch thrill of pulp.

In the only major scholarly article about the “Count of Darkness” series, Janet Lewis floats a theory: Philippe’s compromises are an allegory for the need of the United States to team up with the Soviet Union to defeat Hitler. The Redbook issue with “Gods of Darkness” did hit the stands a few weeks before Pearl Harbor, so maybe some readers saw things that way, but these stories feel less like political exhortations than clumsy studies of people dealing with dark times. Perhaps any sociopolitical message is an accidental echo: Fitzgerald told editor Maxwell Perkins that he enjoyed the escapism of writing about medieval Europe, even if it was risky to write a massive novel that revisited Philippe at three phases of his 60-year career. “The research required for the second two parts would be quite tremendous,” Fitzgerald confessed, “and the book would have been (or would be) a piece of great self indulgence.”

The Philippe stories are self-indulgent, and their rare readers end up disappointed or indifferent. Yet I haven’t seen anyone appreciate one obvious insight in these tales: that if you drop Ernest Hemingway into the crucible of boundless chaos and war, he may seem at first like the sort of man to rebuild the world―but he’ll get in over his head, and he’ll end up believing in nothing.

* * *

The Philippe stories might be more revealing if we read them alongside Fitzgerald’s other work. After the letdown of “Gods of Darkness,” I turned back to This Side of Paradise, his 1920 debut novel. For the medievalist, the highlight of Chapter Two, “Spires and Gargoyles,” is a passage with its own precocious subtitle, “A Damp Symbolic Interlude,” the musings of Princeton underachiever Amory Blaine as he wanders the campus:

The Philippe stories might be more revealing if we read them alongside Fitzgerald’s other work. After the letdown of “Gods of Darkness,” I turned back to This Side of Paradise, his 1920 debut novel. For the medievalist, the highlight of Chapter Two, “Spires and Gargoyles,” is a passage with its own precocious subtitle, “A Damp Symbolic Interlude,” the musings of Princeton underachiever Amory Blaine as he wanders the campus:

The night mist fell. From the moon it rolled, clustered about the spires and towers, and then settled below them, so that the dreaming peaks were still in lofty aspiration toward the sky. Figures that dotted the day like ants now brushed along as shadowy ghosts, in and out of the foreground. The Gothic halls and cloisters were infinitely more mysterious as they loomed suddenly out of the darkness, outlined each by myriad faint squares of yellow light. Indefinitely from somewhere a bell boomed the quarter-hour, and Amory, pausing by the sun-dial, stretched himself out full length on the damp grass. The cool bathed his eyes and slowed the flight of time―time that had crept so insidiously through the lazy April afternoons, seemed so intangible in the long spring twilights. Evening after evening the senior singing had drifted over the campus in melancholy beauty, and through the shell of his undergraduate consciousness had broken a deep and reverent devotion to the gray walls and Gothic peaks and all they symbolized as warehouses of dead ages.

The tower that in view of his window sprang upward, grew into a spire, yearning higher until its uppermost tip was half invisible against the morning skies, gave him the first sense of the transiency and unimportance of the campus figures except as holders of the apostolic succession. He liked knowing that Gothic architecture, with its upward trend, was peculiarly appropriate to universities, and the idea became personal to him. The silent stretches of green, the quiet halls with an occasional late-burning scholastic light held his imagination in a strong grasp, and the chastity of the spire became a symbol of this perception.

“Damn it all,” he whispered aloud, wetting his hands in the damp and running them through his hair. “Next year I work!” Yet he knew that where now the spirit of spires and towers made him dreamily acquiescent, it would then overawe him. Where now he realized only his own inconsequence, effort would make him aware of his own impotency and insufficiency.

The college dreamed on―awake.

Look at what Fitzgerald can do when he knows what he’s doing. To a status-addled Princetonian, the Gothic embodies imagination, ambition, humility, and the weight of tradition all at once. A rainy walk across campus can make the heart swell with giddy confusion. Those three paragraphs show a sensitivity to human emotion that’s absent from dozens of pages about warlords and fort-building.

The nod to Gothic architecture is also a sign of the times. When Fitzgerald attended Princeton from 1913 to 1917, the campus’s oldest Gothic spires were still fairly recent, having been built only after the Civil War, and many of the gargoyles had begun leering down at cocky undergrads only three or four years earlier. Fitzgerald knows to tap into not only the romanticism of Gothic Revival architecture, but also its pretensions. He failed to make sense of the 1930s through the lens of medievalism, but he was smart to see that the Middle Ages could be fertile ground for ambiguous symbolism and complex allusions.

You wouldn’t know it from The Great Gatsby, but Fitzgerald was haunted by medieval shadows. His biggest failure in the “Philippe, Count of Darkness” stories is his inability to figure out if the Middle Ages were a warning about the problems of his own age or the beginning of a way out of them. The mind of a Jazz Age author turns out to have been a Gothic novel: enter the mansion, get lost far beneath it in medieval crypts.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third story about medieval France “shows that national chaos does not fail to bring forth a leader.” That’s the chirpy editorial comment just below the byline in the August 1935 issue of Redbook, and it makes me wonder if the magazine’s staffers actually read the story. By this point, they’re no longer touting Fitzgerald’s contributions on the covers, so readers would have had to stumble upon “The Kingdom in the Dark” while flipping through an issue already packed with other, lighter fiction. I wonder how many of them even remembered

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third story about medieval France “shows that national chaos does not fail to bring forth a leader.” That’s the chirpy editorial comment just below the byline in the August 1935 issue of Redbook, and it makes me wonder if the magazine’s staffers actually read the story. By this point, they’re no longer touting Fitzgerald’s contributions on the covers, so readers would have had to stumble upon “The Kingdom in the Dark” while flipping through an issue already packed with other, lighter fiction. I wonder how many of them even remembered  “But Philippe was wasting his passion,” Fitzgerald writes. “Three days later Louis the Stammerer, King of the West Franks, obligingly died.” That’s the final line of the story, a conclusion that snuffs out whatever embers of tension and conflict that Fitzgerald has spent nine pages struggling to kindle.

“But Philippe was wasting his passion,” Fitzgerald writes. “Three days later Louis the Stammerer, King of the West Franks, obligingly died.” That’s the final line of the story, a conclusion that snuffs out whatever embers of tension and conflict that Fitzgerald has spent nine pages struggling to kindle. It’s a shame that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second “Philippe” story begins with an editor’s lie: “The brilliant thought quality and style of the creator of ‘The Great Gatsby’ are very much in evidence in this majestic story of 879 A.D.” Two lies, really: By design, there’s nothing “majestic” about “The Count of Darkness.” Fitzgerald wallows in sketching out civilization at its lowest ebb, but it turns out that his version of the Middle Ages give him more than he’s prepared to confront.

It’s a shame that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second “Philippe” story begins with an editor’s lie: “The brilliant thought quality and style of the creator of ‘The Great Gatsby’ are very much in evidence in this majestic story of 879 A.D.” Two lies, really: By design, there’s nothing “majestic” about “The Count of Darkness.” Fitzgerald wallows in sketching out civilization at its lowest ebb, but it turns out that his version of the Middle Ages give him more than he’s prepared to confront. But maybe that’s the point. Philippe’s second act that morning is to find women who can cook and clean for the men in his nascent army. He later addresses what he considers a “minor problem”: “announcing to the half-dozen girls who had been rounded up that for the moment each would be permitted her parents’ hut for the night, but that in the future there would be no marriage permitted in the country save with his permission. He would expect them to choose their mates among his own men.” Later, when Philippe spots a Syrian caravan attempting to ford his river, he proposes robbing the merchants before downgrading his plan to merely extorting the heck out of them. Fitzgerald has a lurid preoccupation with how nasty and brutish people get when civilization shatters. He wants to shock and enlighten the magazine-reading public of 1935, like an Ivy League freshman who comes home at Thanksgiving and has grown so much wiser than everyone else.

But maybe that’s the point. Philippe’s second act that morning is to find women who can cook and clean for the men in his nascent army. He later addresses what he considers a “minor problem”: “announcing to the half-dozen girls who had been rounded up that for the moment each would be permitted her parents’ hut for the night, but that in the future there would be no marriage permitted in the country save with his permission. He would expect them to choose their mates among his own men.” Later, when Philippe spots a Syrian caravan attempting to ford his river, he proposes robbing the merchants before downgrading his plan to merely extorting the heck out of them. Fitzgerald has a lurid preoccupation with how nasty and brutish people get when civilization shatters. He wants to shock and enlighten the magazine-reading public of 1935, like an Ivy League freshman who comes home at Thanksgiving and has grown so much wiser than everyone else. Two weeks ago, a footnote jumped out at me like a desperate spark from a dwindling fire. A scholar had ignored what was, to me, a marvel, rushing past it with such haste that he obviously couldn’t dream that I’d want to know more. For eleven years I’ve used this blog to root out medievalism in weird corners of American life—but it had never occurred to me that F. Scott Fitzgerald, of all people, was, for a while, obsessed with writing fiction set in medieval Europe.

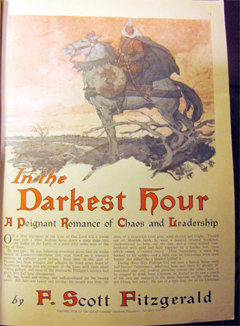

Two weeks ago, a footnote jumped out at me like a desperate spark from a dwindling fire. A scholar had ignored what was, to me, a marvel, rushing past it with such haste that he obviously couldn’t dream that I’d want to know more. For eleven years I’ve used this blog to root out medievalism in weird corners of American life—but it had never occurred to me that F. Scott Fitzgerald, of all people, was, for a while, obsessed with writing fiction set in medieval Europe. An editorial note at the end of the story offers a clue: “F. Scott Fitzgerald has written another vivid drama of the dark ages which even more significantly illuminates recent events in Europe and which will appear in an early issue.” Almost nobody delves into medievalism because they wish they had lived in the real Middle Ages; like many before him and many since, Fitzgerald grabs at a medieval metaphor to help him make sense of the here and now. But is the devastated and chaotic Loire valley of “In the Darkest Hour” the Europe of rising fascism and Nazism? A nation wrecked by the Great Depression? An America greatly changed by immigration? There’s little in the story itself that encourages a reader to see anything here but stilted actors in medieval dress.

An editorial note at the end of the story offers a clue: “F. Scott Fitzgerald has written another vivid drama of the dark ages which even more significantly illuminates recent events in Europe and which will appear in an early issue.” Almost nobody delves into medievalism because they wish they had lived in the real Middle Ages; like many before him and many since, Fitzgerald grabs at a medieval metaphor to help him make sense of the here and now. But is the devastated and chaotic Loire valley of “In the Darkest Hour” the Europe of rising fascism and Nazism? A nation wrecked by the Great Depression? An America greatly changed by immigration? There’s little in the story itself that encourages a reader to see anything here but stilted actors in medieval dress.