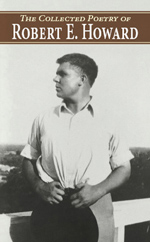

The ghost of Robert E. Howard sleeps fitfully at best. His better stories have been republished by the University of Nebraska Press, but fans still struggle to champion his worth. You know Howard, if you know Howard, from crummy movies about his characters—Kull, Conan, Solomon Kane—even if you’re unaware of the brawny shadow he casts across decades of sword-and-sorcery. Both co-creators of Dungeons & Dragons cited him as an outsized influence, but his prominence as a fantasy writer overshadows the speed with which he also cranked out horror yarns, cowboy tales, historical fiction, and boxing stories from the bedroom of his parents’ Texas home.

The ghost of Robert E. Howard sleeps fitfully at best. His better stories have been republished by the University of Nebraska Press, but fans still struggle to champion his worth. You know Howard, if you know Howard, from crummy movies about his characters—Kull, Conan, Solomon Kane—even if you’re unaware of the brawny shadow he casts across decades of sword-and-sorcery. Both co-creators of Dungeons & Dragons cited him as an outsized influence, but his prominence as a fantasy writer overshadows the speed with which he also cranked out horror yarns, cowboy tales, historical fiction, and boxing stories from the bedroom of his parents’ Texas home.

Before committing suicide in 1936 at the age of 30, Howard published more in twelve years than most of us will in a lifetime, earning his rep as one of the great writers of the pulp era—but Howard wasn’t just a famously frantic storyteller. He was also, as his gravestone points out, a poet. Until recently, few readers knew how madly poetic he was.

At nearly 800 pages, The Collected Poetry of Robert E. Howard, published in 2009, is a monument to its author’s strange and boyish mind. Several of Howard’s 700-odd poems first appeared in pulp magazines like Weird Tales, either as standalone pieces or as epigraphs to stories; many were never published at all. Gathered in one tome (without the bibliographies compiled on a separate website), they’re an almost overwhelming blast from Howard’s mental universe, a cacophonic orgy of Romans, Babylonians, Vikings, cowboys, Crusaders, Mongols, Zulus, cavemen, and voodoo queens—figures who’ve long since been forced from the realm of respectable verse.

Can the collected works of any other poet boast a 60-page section on Wizardry and Satanism? Ah, but here it is, nestled amid sections covering Heroic Verse, War Poems, Horror Poems, Exoticism and Nature, Personal Poems, Historical Poems, Dialect and Doggerel, and Prose Poems. I’d already known some of Howard’s most effective ballads, especially “The King and the Oak” and “Solomon Kane’s Homecoming,” but it’s enlightening to see the good stuff in context. This comprehensive volume proves how many words even the most manic writer has to fling around before breaking free of his influences and pouncing on bright, fleeting lines of his own.

As befit his youth, Howard was an imitative poet, wedding his own stark worldview to the rhythms of Tennyson, Noyes, Chesterton, and others. His imitation of Robert Service and William Blake is particularly obvious, but his better poems show that they taught him how to write deeply creepy verse. “Zukala’s Jest,” for example, sounds less like the invention of a Texan autodidact and more like an ancient chant heard by a traveler who barely escaped with his life. “Memories of Alfred,” about a Saxon who battles the Danes, ends with a line cribbed from Tennyson: “and friend slew friend, not knowing whom he smote.” In Idylls of the King, this line marks the chaos of Arthur’s final battle and the failure of the Arthurian dream, but Tennyson follows it with a sunrise. Howard admits no hope; fratricide is its own poetic end.

Howard’s lack of military service didn’t stop him from writing about modern war, and the resulting poems are an unsatisfying mishmash of Kipling and Siegfried Sassoon—but then, sometimes, a startling phrase presents itself. In the beguiling “White Thunder,” a Cornishman fighting in Flanders during World War I recalls a faraway land where “the clashing crags re-echoed / like a planetary war.” Outside of pop songs, I can’t recall any poets who’ve used sci-fi similes to describe earthly experiences. Howard makes it work; it rightly describes what he saw in his mind.

I’ve been browsing Collected Poetry for more than a year, and my notes are full of pointers to curious bits like these: nice double meanings in lines like “[a]s clouds blow over the mead,” chilling little images, notable exercises in form, parodies of Longfellow, or bizarre poems that almost work but for a few clunky lines, like a lyric that notes (as God knows I never thought to) the absence of Arcadian centaurs on the Creole lawns of New Orleans. Howard, I think, didn’t strive for maturity, but said his piece in the bleak, angry fury of youth. Even when his diction is derivative, he raises his own voice to a roar to drown out the poets he read. His “Song of the Naked Lands” could never be mistaken for Edna St. Vincent Millay:

You raped the grapes of their purple soul

For your wine-cups brimming high;

We stooped to the dregs of the muddy hole

That was bitter with alkalai.

That verse isn’t perfect, but it’s perfectly Howardian. No other poet would snarl while rehearsing one of his favorite themes, the Thomas Cole royal collapsapalooza:

You lolled by fountain and golden hall

Until that frenzied morn

When we burst the gates and breached the wall

And cut you down like corn.

Weirdly, a few pages away, Howard lays aside his weapons and shines in repose. “A Negro Girl,” a short lyric about African echoes in Harlem, might appear in literary anthologies if someone else’s name were attached to it.

Of course, Howard strikes some awful notes. Collected Poetry includes much juvenilia, doggerel, and diction I’d never defend. In “The Song of the Last Briton,” Howard dubs Saxon longships “millipedes of doom,” and he habitually strides into awful rhymes: prophet/Tophet, strident/trident, lizard/wizard, strange-and-hoary/Purgatory. Some off-rhymes hint at his own accent—”dour” and “moor”—while others reveal the limits of his travels and education. “Lithe,” for example, doesn’t rhyme with “myth.” Perhaps Howard never heard the word spoken, and only read it in books.

Splayed as they are across hundreds of pages, Howard’s flaws are obvious, but dwelling on his clunkers holds him to a standard we’d scarcely meet ourselves. How many high-school graduates, or even educated genre authors, can write a proper ballad or sonnet and conjure hundreds of literary references and historical allusions from sulfurous mental fog? How many boys doze off in English class because no one made clear that poetry is also the province of Satanic wizards, voodoo queens, blood-flecked Vikings, Puritan swordsmen, and frantic barbarian hordes?

Howard holds no place in the history of American poetry. Some entries in Collected Poetry show that he was aware of free verse, but he continued to compose formal, narrative poems for readers whose tastes were undeterred by the literary trends of the day. In keeping with Sturgeon’s Law, much of Howard’s work is derivative, but his worst is no worse than many of the Georgian poets who were his overseas predecessors, and he’s certainly more persistent in his own weird vision than the authors of the wan, formless sighs I skim in Poetry magazine every month. And when Howard is good, he’s a big, brawny blast.

Collected Poetry, which is already out of print, is far more Howard than most people need—I didn’t, and can’t, read every poem in the book—but teachers and parents fretting over “reluctant readers” should explore the shorter Selected Poems, available in print-on-demand. Howard’s works are case studies in form and tone, and they fling open the gates to discussions about medieval lands, ancient empires, violence, decadence, and the decline of civilizations. They’re also grand, lurid proof that poetry sometimes has hair on its chest.

“Howard is manic-depressive, courageous, and self-destructively human,” Steve Eng writes in his 1984 essay “Barbarian Bard,” reprinted as the introduction to Collected Poetry. “At his best, he carries the reader forward like a trussed captive, astride a black horse with crimson hooves, headlong off that final cliff toward the sharp rocks of Death below.” Eng’s epitaph suggests what Robert E. Howard ought to become: the poet laureate of restless boys, whose lives these days lack poetry, but who, as Howard comprehended, crave it more than most.

In 2007, I translated the 15th-century romance “The Taill of Rauf Coilyear,” a 972-line Middle Scots poem about the kerfuffle that ensues when Charlemagne, separated from his entourage by a snowstorm at Christmastime, seeks refuge in the home of a proud and irascible collier (a sort of medieval Tommy Saxondale). Combining folklore motifs with burlesque humor and elements of chansons and chivalric romances, “Rauf Coilyear” is a lively but rarely-read tale of courtesy, hospitality, and knighthood. To my knowledge, it’s also the only medieval romance in which Charlemagne totally gets slapped in the face.

In 2007, I translated the 15th-century romance “The Taill of Rauf Coilyear,” a 972-line Middle Scots poem about the kerfuffle that ensues when Charlemagne, separated from his entourage by a snowstorm at Christmastime, seeks refuge in the home of a proud and irascible collier (a sort of medieval Tommy Saxondale). Combining folklore motifs with burlesque humor and elements of chansons and chivalric romances, “Rauf Coilyear” is a lively but rarely-read tale of courtesy, hospitality, and knighthood. To my knowledge, it’s also the only medieval romance in which Charlemagne totally gets slapped in the face.

I’m not a book collector, but I am a book accumulator, so I haunt the D.C. area’s secondhand shops in joyful hope of discovering something peculiar and new.

I’m not a book collector, but I am a book accumulator, so I haunt the D.C. area’s secondhand shops in joyful hope of discovering something peculiar and new.

“The evening passed delightfully: we sat out in the moonlight on the piazza, and strolled along the banks of the Patapsco; after which I went to bed, had a sweet night’s sleep, and dreamt I was in Mahomet’s Paradise.”

“The evening passed delightfully: we sat out in the moonlight on the piazza, and strolled along the banks of the Patapsco; after which I went to bed, had a sweet night’s sleep, and dreamt I was in Mahomet’s Paradise.”

“The origin of our city will be buried in eternal oblivion,” wrote Washington Irving in his satirical

“The origin of our city will be buried in eternal oblivion,” wrote Washington Irving in his satirical

[This post is a rerun from 2010; I felt like bringing it back for a second spin. – J.S.]

[This post is a rerun from 2010; I felt like bringing it back for a second spin. – J.S.]

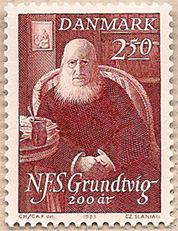

“Imagine a contemporary translation of Dante that includes references to Pink Floyd, South Park, Donald Rumsfeld, and Star Trek,”

“Imagine a contemporary translation of Dante that includes references to Pink Floyd, South Park, Donald Rumsfeld, and Star Trek,”  For half a century,

For half a century,  The ghost of Robert E. Howard sleeps fitfully at best. His better stories have been republished by the University of Nebraska Press, but fans still struggle to champion his worth. You know Howard, if you know Howard, from crummy movies about his characters—

The ghost of Robert E. Howard sleeps fitfully at best. His better stories have been republished by the University of Nebraska Press, but fans still struggle to champion his worth. You know Howard, if you know Howard, from crummy movies about his characters—