A while back, two poets independently responded to my gargoyle-poem book by asking me if I knew Maryann Corbett. I didn’t, but when I looked her up, I was pleasantly stunned to find someone whose modus operandi I understood: a poet who tends to the formal, a medievalist who holds a non-academic day job. Her latest book, Mid Evil, collects only 40 poems, but together they show how we frame our yearnings with fragments of the past—both the world’s and our own.

A while back, two poets independently responded to my gargoyle-poem book by asking me if I knew Maryann Corbett. I didn’t, but when I looked her up, I was pleasantly stunned to find someone whose modus operandi I understood: a poet who tends to the formal, a medievalist who holds a non-academic day job. Her latest book, Mid Evil, collects only 40 poems, but together they show how we frame our yearnings with fragments of the past—both the world’s and our own.

At first, all I saw was Corbett’s medievalism. Mid Evil takes its title from a poem about an blasé student’s chronic misspellings; the book also includes poems about studying medieval manuscripts, facing cancer in light of Cathar heresies, seeing The Return of the King with costumed teenagers, and imagining J.R.R. Tolkien’s inner life. Corbett is a skilled translator, so Mid Evil includes modern English versions of several medieval poems: the Old English “Deor” and three Exeter Book riddles, all of them in a form that recalls Anglo-Saxon alliterative lines; two balades from the French of Christine de Pizan; and verses from Alcuin about a nightingale, rendered in a meter that evokes the long Latin lines of the original.

When medievalism inspires new works of art, I’m intrigued and delighted, so I might have decided that all this was enough. On a hunch, though, I decided to read Mid Evil not as a miscellany but as a collection with purposeful organization. What emerged was an even more meaningful book: the story of a halting but ongoing pilgrimage.

Appropriately, Mid Evil opens with two poems in which old books provoke unexpected emotion. In “Paleography,” Corbett describes the intermingled confusion and enthusiasm that comes from trying to read 16th-century handwriting, which leaves her feeling “like the child who listened, puzzled / by the cries in the next room.” She lets the reader decide whether her experience is a sign of cosmic immaturity or a rare opportunity for the renewal she later craves. In “Hand,” she finds a colophon in a Middle English manuscript that reads “pray for him that made this book,” which pits skepticism against faith but leads Corbett to contemplate the actual, physical existence of the long-dead scribe and to “wonder how long the bones of a hand would last.”

In Corbett’s poetry, such relics are forever surprising us; they suggest a larger, more more challenging context to our lives. A teacup, for example, is a tribute to centuries of human activity—slavery, alchemy, religion, myth—culminating in the morning sip that affords the poet a moment of peace. A blue bowl tells the story of the aging and the dead and holds memories of a loud, insulting father:

“Depression glass.” Imagine it: her mother,

using that gimcrack thing for sixty years,

remembering how a speechless misery feels.

A kind of sore the mind keeps picking at.

I think she’s kept a lot of things like that.And see, the mother’s still around. That’s why

she hasn’t sold it yet to an antique store.

I’ve often told her that would be a mercy.

Honey, it would. That’s what collecting’s for.

Restoring things. We clear the clouds away

so people see good things for what they are.

If mundane objects can resonate with meaning, so can our lives, as long as we’re open to seeing them as stories. In “The Return of the King Screens at Midnight at the Multiplex,” Corbett’s disputatio between skepticism and faith takes on a secular cast as she notes a conflict familiar to medievalists: the detached study of the scholar versus the playfulness of the costumed fan. She realizes it’s not a conflict at all, but reason for an overdue reprimand:

And I

am riven in the dark, remembering

how, long ago, I swore the only wayinto these glamours was to learn to sing

in ancient grammar. Oh my misspent youth:

As well escape your life with imaginingas riddle through the words of some dead mouth.

Settling into her theater seat, she bids herself “[t]o hear the tale that salves the sting of truth” and to think about the fleeting value of fantasy and escapism. “So make your minds / more bloody,” she later exhorts girls shopping for Halloween costumes at Goodwill, hoping they’ll revel in pretending to be monsters. Otherwise, they’ll miss a youthful opportunity, however modest, to experience something beyond themselves, like the hapless undergraduate of “Mid Evil”:

And the last blow is this, your final exam,

in which, over and over, you call the course

mid evil literature. Yes, I suppose

for you that is the word. We both are lost here,

mapless in Middle Earth and muddling through.

You’ll claim your paper. Mild civilities

will be exchanged, and then you’ll lope away,

a sad C minus in your grip ensuring

we’re done. It’s mid-December. Snow will fall—

hrim ond hrið, but no one says that now,

since this is the sphere of Time, beneath the moon,

where everything must change, and where the poems

evaporate like hoar-frost in the sun.

Poems, movies, stories, myths—they shore us against aimlessness, but they also nudge us toward generosity. Faced with a storyteller in “The Pandhandler’s Tale,” Corbett puts aside her reservations and welcomes “the willing suspension of disbelief, / which lets us yield ourselves to the tale of wonder,” even though she only ends up attracting more panhandlers. The experience is real regardless; we’ve avoided a mystery, perhaps even a moment of grace, by assuming a story is false. Imagining one of the Brothers Grimm rewriting tales told by a cowherd’s wife, Corbett wonders: “Does it matter / that now we know how far from truth it falls?” A poem about Abelard and Eloise finds fault with all parties, but encourages interpretation: “What can we know? Perhaps less love than pride / led to their woes. Read their own words. Decide.”

But myth, fantasy, stories, and scholarship all have their limitations, as Corbett makes clear in several poems with a tragic edge. A fond memory of watching the rousing “Victory at Sea” on television in the 1950s darkens with the adult realization that the veteran who was dozing in a nearby armchair likely saw horrific things; simple stories are for children. The myths in fashion magazines prove useless decades after our teenage years; a mysteriously returned gift from a daughter’s long-ago lover shocks us out of our personal fables and into complex reality. Even history itself has limited value: in “The Historian Considers the End Time,” a scholar wracked by cancer is tempted by the Cathars’ heresy of the evil of the body, but her medievalism is useless. She can only hope to leave behind scant relics that give meaning to someone else:

They must, those thirteenth-century prelates,

have known it with a blazing certainty,

the truth he’s going to know then, when he hugs

the clothes that hold her fragrance, when his chest knots

as he cleans her closet, when months past the funeral

he finds in a broom strands of the long, dark hair.

So what do we do when the shadow of nothingness looms? All of Corbett’s thematic strands rise and converge in “Sing, My Tongue,” the final section of Mid Evil. These seven poems find strength and revelation in singing as Corbett invites us to join her in church. “On Singing the Exultet” puts us in the choir at the start of the Easter Vigil, where the singer marvels at the audacity of what she is about to do:

It’s candlelight that makes it possible.

How otherwise could you, with your puny pipes,

expect to do this? yell to the end of space—

where air won’t carry sound—and order the nebulae

Exult? But here you are: you’re going to dare it.

Even feeling insignificant implies a cosmic context for our lives, as “the light of the unforeseen”

burnishes a quiet table

where lover and beloved look at each other

weighing a question that will change the world.

That has already changed it.

In these closing poems, Corbett grapples with doubt while singing at a funeral; one page later, she crashes to earth after the high of singing Mozart with an orchestra in a cathedral. “I’ve come to feel / how all my feasts are haunted,” she says after a child interrupts her attempt to find focus in church, and she falls back on translating Alcuin, who exhorts the nightingale to sing without end: “Sour as my soul had become, you could fill it with honeying sweetness.” She ends on a note of fatigue, physical and spiritual, but despite being disheartened by “wheezing gasps where nothing is inspired,” she still hopes for profundity:

I want it back: the confidence in air—

ruah, pneuma, spiritus—the breath

that stirs the vocal folds of nuns in choir.

The breath that Is. The sound of something there

guiding this gusty round of birth and death.

The rush of driving wind. The tongues of fire.

Mid Evil starts with scholarly study and ends in a wish for religious exultation; it begins with writing and ends in song, becoming a prayer for inspiration, confidence, purpose, and grace. Whether that prayer can or will receive an answer remains, for Corbett, an open question, but she comes to a conclusion I gladly endorse: that myth and medievalism are promising places to start.

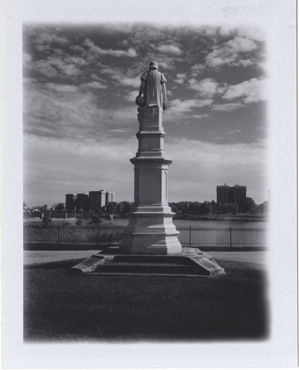

I spent the day before Columbus Day doing research at the Johns Hopkins library—but when I was done, I roamed the city looking for something medieval to photograph. There’s a statue of William “Braveheart” Wallace along the reservoir in Druid Hill Park, but the afternoon light fell far more serendipitously on this Christopher Columbus monument from 1892.

I spent the day before Columbus Day doing research at the Johns Hopkins library—but when I was done, I roamed the city looking for something medieval to photograph. There’s a statue of William “Braveheart” Wallace along the reservoir in Druid Hill Park, but the afternoon light fell far more serendipitously on this Christopher Columbus monument from 1892. No, gnomes aren’t medieval, but they are rooted in 19th-century European medievalism, and there’s certainly a medieval tradition of wee woodland beings making trouble for us humans. Some Anglo-Saxon charms even blame certain types of pain and disease on wicked little “elves.” (Plus, this gnome is made out of felt, the discovery of which is

No, gnomes aren’t medieval, but they are rooted in 19th-century European medievalism, and there’s certainly a medieval tradition of wee woodland beings making trouble for us humans. Some Anglo-Saxon charms even blame certain types of pain and disease on wicked little “elves.” (Plus, this gnome is made out of felt, the discovery of which is

“…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”

“…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”

For all the violence the Vikings unleashed, their enemies and victims might find cold comfort in the torments Americans now inflict on them. We’ve twisted them into beloved ancestors, corny mascots, symbolic immigrants, religious touchstones, comic relief—and, this week,

For all the violence the Vikings unleashed, their enemies and victims might find cold comfort in the torments Americans now inflict on them. We’ve twisted them into beloved ancestors, corny mascots, symbolic immigrants, religious touchstones, comic relief—and, this week,  Likewise, science-fiction fans are forever congratulating themselves for holding the right opinions on such subjects as evolution, but this time they lazily succumbed to fannish fantasies, failing to question a claim that deserved to be pummeled by doubt. I’ve done tons of social-media copywriting, so I get why that blogger just wanted to throw something out there after a holiday to beguile weekend-weary eyeballs—but come on.

Likewise, science-fiction fans are forever congratulating themselves for holding the right opinions on such subjects as evolution, but this time they lazily succumbed to fannish fantasies, failing to question a claim that deserved to be pummeled by doubt. I’ve done tons of social-media copywriting, so I get why that blogger just wanted to throw something out there after a holiday to beguile weekend-weary eyeballs—but come on. I was heartened to find them right where I left them: the

I was heartened to find them right where I left them: the