“Your life will be written / your written life lost”: That’s the prophecy a noblewoman dreams about her unborn daughter in the eerie prelude to Need-Fire, a slim but remarkable book that I can scarcely believe someone wrote. That girl will grow up to become one of the most influential women in Anglo-Saxon England, but most of her story will be forgotten, giving poet Becky Gould Gibson a chance to rescue her from obscurity—and to demonstrate that using poetry to tell longer, more complicated stories is an art we haven’t yet lost.

“Your life will be written / your written life lost”: That’s the prophecy a noblewoman dreams about her unborn daughter in the eerie prelude to Need-Fire, a slim but remarkable book that I can scarcely believe someone wrote. That girl will grow up to become one of the most influential women in Anglo-Saxon England, but most of her story will be forgotten, giving poet Becky Gould Gibson a chance to rescue her from obscurity—and to demonstrate that using poetry to tell longer, more complicated stories is an art we haven’t yet lost.

In 25 interconnected poems, Need-Fire dramatizes the lives of Hild and Aelfflaed, the two women who ran the double monastery that housed both men and women at Whitby in North Yorkshire during the seventh century. Hild educated five bishops, presided over the synod that pushed the English church closer to Rome, and served as abbess when the cowherd Caedmon, the first named English poet, reluctantly sang his first verse. Unfortunately, only a few pages in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History hint at Hild’s profound influence, and the other 29 women known to have run double monasteries in Anglo-Saxon England are hardly more than names. Gibson’s goal is to commemorate them, intertwining her own imagination with copious research to sing them back into life.

And so Gibson invents her own form: short, sparsely punctuated lines that resemble Anglo-Saxon verse, printed with a caesura in the middle of each. These lines don’t follow the rules of Old English meter and alliteration, which makes them feel like fragments straining to be heard across 1,400 years. The result is a stream-of-consciousness narrative that derives subtle power from the poet’s decision to rely on words derived only from Old English. Here’s Hild’s mother’s lament as she bathes her infant daughter:

Glass crosses the water from Gaul

for church windows in your name

yet nothing you say will be found

only the little said of you

Why then stay up late daughter

evening by evening candle by candle

shaping thoughts never to be kept

in your smooth steady hand?

Of course, you don’t need to know Anglo-Saxon scansion to enjoy Gibson’s poetry, nor do you need to scrutinize the historical notes and scholarly addenda that follow each poem. I enjoyed them—Need-Fire is one of those rare books for which I feel like the ideal reader—but you don’t have to be a medievalist to step into Gibson’s weird and haunting world. You just need to be willing to read an historical novel in telegraphic verse.

In Gibson’s hands, Hild is a “child with a will never settled.” We meet her as a teenager eavesdropping on her uncle, King Edwin, as he and his advisers kick around the pros and cons of Christianity. Overhearing the parable about a sparrow that flies through a mead-hall in winter, enjoying a moment of safety and comfort before it returns to the harsh unknown, Hild doesn’t assume, as the king’s men do, that any religion shedding a bit more light on past and future mysteries is worth considering. Instead, she imagines that the sparrow is as lost as she feels:

She’s seen that sparrow beat wild

about the walls looking for a way out

how she feels most of the time

when grownups talk Where will she go

after she dies? Where’s Father now?

She shivers damp to the bone

A keen observer of a land where “[f]olks still/worship sticks,” Hild is beset by secret doubts. The real Hild was all packed up and ready to live with her sister near Paris, but she turned back at the last minute and established a hardscrabble monastery along the North Sea. Gibson might have chalked up this decision to an irrefutable religious vision, but her Hild believes it’s her duty to found institutions that promote peace and education in her war-torn kingdom. And so Gibson takes up the tricky task of dramatizing the apprehension that accompanies faith:

Truly I wonder

when bone becomes spindle

cliffs whittle to teeth

how many or rather how few

will have traded their wooden war gods

for this sad-eyed Hebrew man

As Hild lives a harsh life of religious service that demands great leaps of faith, her doubts mature into greater complexity. She worries less about the “the idle or giddy” in her flock and more about the monks and nuns who are unquestioning and meek, a sensibility that at times feels too 21st century. It flatters us to believe, for example, that a seventh-century woman couldn’t possibly have cared how monks cut their hair or what the date of Easter ought to be. Fortunately, Gibson understands the medieval mind, and she knows that a woman like Hild would eventually conclude that regularity rather than fervor offers solace and bolsters faith:

Belief’s a skill like any other

we’re schooled in must work at daily

What I’ve learned keep learning

rule gives us rooms of time

to breathe in Without rule we are lost

Though Gibson’s form never varies, Need-Fire offers a fine and convincing array of other voices and perspectives: a monk terrified by an eclipse, a young nun dying of the plague, and another nun forced to write a thank-you letter to the author of a virginity handbook for women. (“At least we won’t die in childbirth,” she quips, “though we may die of boredom.”) Mothers and nuns have prescient dreams, abbesses’ bones cry out from their graves, and even God Himself weighs in, gently chiding his seventh-century children in verses they’re bound not to hear.

Gibson’s imagery is fresh, too. When Etheldreda, abbess of Ely, writes to her husband to warn him of a sneak attack, she muses on the extent to which her life revolves around eels. She spears them, salts and skewers them for Lent, observes their mating habits, and finds in them a homely metaphor:

What is man in the clutches

of sin but an eel

on an eel-fork shivering?

Eels by the thousands

eels almost bodiless

[…]

God will keep you He keeps

us all How does an eel go

with no fins to speak of?

Yet she takes to the sea

knowing she’ll get there

lay eggs and die

knowledge older than man

deep in her brain

The eel poem helps Need-Fire build to a thematic climax. Through layers of fine detail, Gibson builds her seventh-century world with careful references to native animals and plants and the things humans make from them, from salted herring to wormwood mulled in ale. Above all, this book pays tribute to forgotten women who did important work, but it also challenges readers to marvel at the infinite variety of nature, which Gibson sees, like many medieval people before her, as reflecting the nature of God. Simply walking outside is an inexhaustible antidote to boredom and, as a nun named Begu finds when she holds a mussel shell, a potential bestower of greater rewards:

When I stare

into its pool of blackness

it tells me I’m here

Small wonder! God always

shines back if we’re looking

Blending scholarship, biography, and historical fiction, Need-Fire needs to be read at a careful pace that duly honors its subjects’ lives. Writers who rescue obscure figures from history’s margins aren’t always capable of dropping them into good stories, but by retelling the lives of Hild and Aelfflaed in stark, anecdotal poetry rather than a novel, Gibson crafts scenes that defy the monotony of the form she’s chosen to labor within, just as her characters do. Need-Fire isn’t a dutiful exercise in social history, but an eloquent argument that these abbesses and the men and women around them were real and alive, not stock characters in medieval-ish fiction.

Europeans and Americans have never been able to decide whether medieval people were our predecessors and brethren or the makers of a world that was grotesque, alien, unfathomably strange. There’s no reason both can’t be true, and Gibson shows us that an age we’d find physically and culturally inhospitable is also emotionally and intellectually welcoming. Fourteen centuries on, she hears familiar notes of doubt, desperation, and hope:

what is any of us but one

of God’s beings scrambling

for a foot-hold on crumbling cliffs?

One hundred years ago today,

One hundred years ago today,  “Your life will be written / your written life lost”: That’s the prophecy a noblewoman dreams about her unborn daughter in the eerie prelude to

“Your life will be written / your written life lost”: That’s the prophecy a noblewoman dreams about her unborn daughter in the eerie prelude to  Back in December,

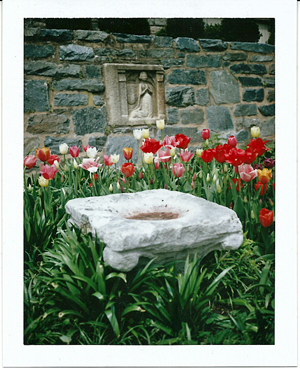

Back in December,  Every Easter, the All Hallows Guild at Washington National Cathedral plants gorgeous rows of tulips along the northern border of the Bishop’s Garden. This year, I saw Easter Sunday as an opportunity to test the Land Camera’s eye for color.

Every Easter, the All Hallows Guild at Washington National Cathedral plants gorgeous rows of tulips along the northern border of the Bishop’s Garden. This year, I saw Easter Sunday as an opportunity to test the Land Camera’s eye for color. Polaroid didn’t offer an extensive line of accessories for the Land Camera, but their add-ons did include a

Polaroid didn’t offer an extensive line of accessories for the Land Camera, but their add-ons did include a  This

This  “…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”

“…but alle shalle be wele, and alle shalle be wele, and alle maner of thinge shall be wel.”

Because I’m always on the lookout for medievalism, I was naturally drawn to Tod Wodicka’s 2008 novel

Because I’m always on the lookout for medievalism, I was naturally drawn to Tod Wodicka’s 2008 novel

Nestled in the Caucasus like a goblet of leopard blood in Vladimir Putin’s mailed fist, Sochi is basking in worldwide attention. The Black Sea site of the Winter Olympics is just up the coast from the Georgian border, and the media is starting to ponder this umbrous and ungenteel land: Sky News offers a primer on

Nestled in the Caucasus like a goblet of leopard blood in Vladimir Putin’s mailed fist, Sochi is basking in worldwide attention. The Black Sea site of the Winter Olympics is just up the coast from the Georgian border, and the media is starting to ponder this umbrous and ungenteel land: Sky News offers a primer on