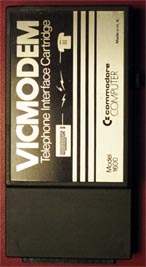

Twenty-three years ago this month, I convinced my folks to drive me to the toy store to buy something that toy stores no longer sell. Most people didn’t know what a modem was, but when I whipped up an ASCII animation showing us making the trip as a family and emerging in triumph from the Toys R Us, my parents were amused enough to give me a lift, if understandably skeptical. In 1986, the online world was too tiny to be mythologized. Wild stories about local kids “changing the positions of satellites up in the blue heavens” sometimes made the news, but online bulletin-boards were “here there be dragons” outlands for all but a few, and no one noticed gaming pioneers as they racked up monstrous Compuserve bills playing Hangman at 300 baud.

Twenty-three years ago this month, I convinced my folks to drive me to the toy store to buy something that toy stores no longer sell. Most people didn’t know what a modem was, but when I whipped up an ASCII animation showing us making the trip as a family and emerging in triumph from the Toys R Us, my parents were amused enough to give me a lift, if understandably skeptical. In 1986, the online world was too tiny to be mythologized. Wild stories about local kids “changing the positions of satellites up in the blue heavens” sometimes made the news, but online bulletin-boards were “here there be dragons” outlands for all but a few, and no one noticed gaming pioneers as they racked up monstrous Compuserve bills playing Hangman at 300 baud.

Lacking any real plan, I used my modem to connect to a suburban archipelago of slow, single-line BBSes, not knowing that the experience would teach me how to write. A few years later, when I was the only English major banging out e-mail on an X-term in the basement of the computer science building, I didn’t know I was an early adapter of a network that would soon link millions of offices and homes while uprooting the business models of several industries, including publishing. I only knew that I sensed opportunity.

I thought about those days when I read Jake Seliger’s post about a New York Times article pointing out the obvious: the online market for used books is a boon for readers. Jake wondered how cheap books will affect the business of publishing, and while I don’t know what the future holds for companies that can’t adapt, I told him I didn’t think a bonanza of secondhand books was necessarily bad for authors:

As someone who recently entered the publishing world as a lower-midlist author, I’ve thought quite a bit about the implications of the online market for used and discount books. When someone buys my book used on Amazon for $4 instead of paying $12 for a new paperback, that’s around 75 cents in royalties I don’t see—but I’d be awfully short-sighted to gripe about that, because the glorious churn of the used-book market may help me in the long run. Today’s budget-conscious undergraduate may be tomorrow’s history teacher; perhaps he’ll assign my book to his class of twenty students five years from now. Or maybe he’ll recommend the book to a friend who then downloads a copy to his Kindle, thereby putting around $2 in my pocket. Or maybe he hates the book so much that he strenuously avoids my next one, thus sparing me a one-star Amazon review that would have dissuaded potential readers.

Who knows? I do know that I’d be a fool to gripe about the Internet, because thanks to the Web–which includes everything from Amazon to bloggers to podcasts to the online BookTV archives—I’ve sold more copies of my book than the 50 or so secondhand copies currently listed on Amazon. Fretful authors and publishers who dread the advent of the hyper-efficient online book market may yet be vindicated, but I’m not convinced that budget-conscious book-buyers are the only ones who stand to benefit from it.

Compared to a fantasy world in which Amazon, the big bookstore chains, and used-book dealers simultaneously thrive (and where all of our orders are, presumably, delivered by a Deschanel sister on a flying unicorn), the current situation looks bleak—but as an author, a voracious book-buyer, and someone who’d be nowhere without the Internet, I prefer the here-and-now to the real world of twenty years ago, when a suburban “bookstore” was a nook in the mall stocked only with bestsellers, a few shelves of genre fiction, some classics, and the latest comic-strip anthologies.

Whether my career thrives or stalls, I’m glad I’m a writer now. I can get obscure articles in minutes rather then weeks, and people on the subway can use a telephone to order and read my books from stores that never close. Best of all, my cable modem is more than 6,500 times faster than the modem I bought in 1986, but it cost the same amount: around 60 bucks (or half the price in 1986 dollars). Confusion may be justified, but hold off on the Anglo-Saxon elegies; not everything is worse than it used to be.

That’s a photo of the bibliography of

That’s a photo of the bibliography of