“The old year limps to its grave, ashamed,” mutters some uncomfortable actor in Sword of the Valiant, a movie that’s otherwise hard to recommend for either its eloquence or its insight. At first, I thought Christopher Howse’s review of the new Medieval and Renaissance Galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum might prove to be an equally hollow endorsement of all things medieval, especialle because Howse embarrasses himself by howling about television, sneakers, and Kids These Days.

But then, with crusty wit, he writes this:

Thus it was, at the V&A, that as I stood in front of a splendid five-foot painted and gilt statue of St Roche and his dog (from about 1540), two women came up and glanced at it. “I like the dog,” said one. “He’s licking his leg,” said the other, and they moved on.

In 1540, every peasant or Cockney in Christendom knew all about St Roche. They could see not only the statue but also what it was about: the saint of the plague years, whose dog licked his sores and brought him bread. For it was always a libel to call stained-glass windows “the Bible of the poor”. The poor might not be able to read. But they knew their Bible and saints’ lives, or they’d never have been able to make out what the pictures meant. Modern tourists are more ignorant and purblind than the most sore-smeared Chaucerian beggar.

Today, what we wear is ugly, though the meanest medieval labourer wore hand-made clothes. We can’t name the stars, except the ones we see on TV. We can read, but can’t be bothered to. We save time by driving, only to lose it by slumping on the sofa. We can’t sing, can’t dance, can’t paint and can’t drink politely in company. Yet we have the childish gall to patronise past centuries as inferiors.

In Howse’s place, I might not have so readily drowned my opinion in a cauldron of molten snide nor so openly pined for medieval ways. Even so, whether medieval people infuriate or intrigue you, the full range of their humanity is worth remembering, especially on New Year’s Eve. Janus, after all, has two faces; the one that looks backwards sees truths that the other face still needs to know.

So you’re cruising through suburban Maryland on a rainy Sunday afternoon. Daylight is fading, just as a semester spent focused on

So you’re cruising through suburban Maryland on a rainy Sunday afternoon. Daylight is fading, just as a semester spent focused on

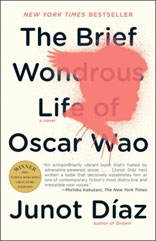

Life was funny, growing up around characters but not inside a story. I’m not complaining; it was simply true that stories happened in New York or in California, on the shores of

Life was funny, growing up around characters but not inside a story. I’m not complaining; it was simply true that stories happened in New York or in California, on the shores of