Every so often, I stumble onto some relic of American medievalism that seems charming but inconsequential—until a bit of digging brings out something more.

Every so often, I stumble onto some relic of American medievalism that seems charming but inconsequential—until a bit of digging brings out something more.

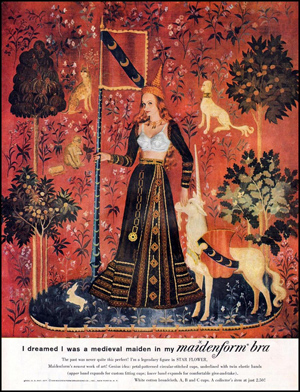

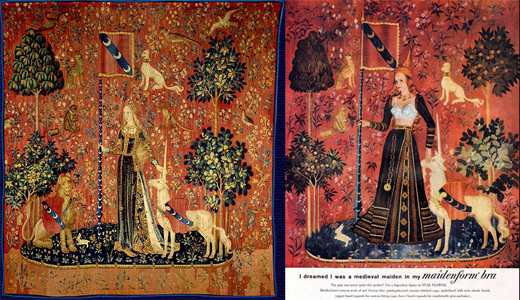

Behold: “I dreamed I was a medieval maiden in my Maidenform bra,” an ad that ran in magazines in 1959 and 1960. (Click here to see it larger.) The ad is based on the late-15th-century “Lady and the Unicorn” tapestries designed in Paris, woven in Flanders, and now on display at the Musée National du Moyen Âge in Cluny. Five of the tapestries are devoted to the senses; a sixth tapestry has been variously interpreted.

Maidenform’s “I Dreamed…” campaign, which began in 1949 and ran for 20 years, was apparently so successful that it’s still studied in business schools. The other ads weren’t medievally themed, but they all showed a shirtless woman in some professional or historical setting. The “medieval maiden” ad stands out, though, for its fidelity to its source.

Place the ad and the tapestry side by side and you can see how little got removed (other than the maiden’s blouse).

The heraldic symbols on the banner (and on the unicorn’s little Thundershirt-shield) are intact, even though they’re meaningless now. The grimacing lion is gone; modern people might have have been distracted by him or found him comical. The woman no longer holds the unicorn’s horn but caresses it near its mouth. She’s also been decked out in a hat on loan, I would guess, from the neighborhood gnome.

Maidenform was determined to portray not just some fantasy scene, but a real and very specific medieval work. Why?

Maidenform was determined to portray not just some fantasy scene, but a real and very specific medieval work. Why?

For one thing, the decade leading up to this ad was florid with chivalry, at least at the movies: Rogues of Sherwood Forest, Ivanhoe, Richard and the Crusaders, Knights of the Round Table, Prince Valiant, Lady Godiva, The Court Jester, Saint Joan, The Vikings, and at least two TV versions of A Connecticut Yankee. (With The Seventh Seal and The Virgin Spring, Ingmar Bergman cast a pall over these Technicolor revels, but he was an anomaly.) It’s no wonder that a couple years later, the press was quick to cast John F. Kennedy’s candidacy and presidency in terms of fair ladies and storybook heroes—even if there’d be no “Camelot” talk until after his assassination.

But maybe the Maidenform maiden is more of a high-culture dream. At the end of the 1950s, tapestries were big news: A decade earlier, the Metropolitan Museum of Art had hosted a show about French tapestries from 1375 to the present, and in 1958 and 1959 the Cloisters made two major tapestry acquisitions. In 1959, the Philadelphia Museum of Art acquired several tapestries about the exploits of Constantine, while the Brooklyn Museum showed off Norwegian tapestries from the 16th through 18th centuries.

(…and curiously, the New York Times reported in May 1958 that sculptor Elbert Weinberg had installed a terra-cotta lady-and-unicorn in the lobby of 405 Park Avenue.)

In 1959, American medievalism was enjoying a sort of historicist autumn. Renaissance fairs were a few years off and Tolkienesque fantasy had yet to go mainstream, so when people thought of the Middle Ages, they imagined the tidy past they enjoyed in movies—and, apparently, in magazine ads. It took me only a few minutes to find several advertisements from 1958 to 1960 that make the Middle Ages look as pleasant as it did in the movies of the time.

Plymouth Gin evoked jousting to invite Americans to join an international band of drinkers, pharma giant Parke-Davis paid tribute to hospitals in 12th-century France, Chivas Regal reveled in Scottish heritage, and the Grant Pulley and Hardware Corporation, makers of sliding doors, assumed you would know what a “portcullis” was. The medieval people in these ads—knights, nurses, architects—set precedents, and served as examples.

When Austrian historian Herwig Wolfram considered American medievalism in the 1970s, he saw more than folly. “What might sometimes appear to a European as slightly comical is nevertheless an expression of astonishing vitality,” he wrote. “And what many a dry pedant might dismiss as low-brow is in reality a kind of learning experience on a level different from that to which most Europeans are accustomed.” Interweaving high and not-so-high culture, the Maidenform ad shows the mass appeal of America’s medieval dream, even if nobody’s heeding the small print: “The past was never quite this perfect!”

Am loving the “ant”-ic nature of this post’s title!

LikeLike

Thank you—I had hoped somebody would!

LikeLike

I can recall seeing these in old magazines when I was a kid in the 1970s. Now I want to go buy vintage copies on eBay.

No I don’t. Even so, this is fantastic and fascinating. I’m linking this post.

LikeLike

Thanks, Diane. Am I right in recalling that you have an interest in costume and textile history? If so, I’ll keep an eye for more neat stuff…

LikeLike

The Cluny tapestries are on the walls in the Griffindor Common Room in the Potter movies, and “The Unicorn in Captivity” from “The Hunt of the Unicorn” tapestry series is in the room of requirement when it’s the room of hidden things. (Can you tell I have three children?)

So I suppose they manage to invoke, at least a little the alchemical and Christian symbolism of the books… which I read aloud to my youngest over many, many nights.

So I guess you’d have to say the images are still well-referenced and deeply appealing to a large segment of the population!

LikeLike

Hey, that’s neat! The Cloisters recently exhibited the Lewis Chessmen, which also appear in the Potter movies. I wonder if some ambitious curator out there dreams of gathering all of the medieval objects that have made cameos in those movies into one highly unlikely mega-exhibition?

LikeLike