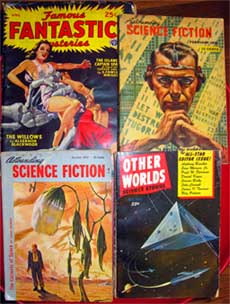

Where books get stacked rarely makes a statement, but at Wonder Book, the shelves above and around the bathroom door are stuffed and piled with pulps: Astounding, Galaxy, and countless others, most of them from the 1950s, some of them hiding their half-shredded kin from the ’30s and ’40s. The expensive stuff is aisles away, bagged and secure behind glass, so these are the five-dollar specials, what remains after anthologists spent half a century picking their carcasses clean.

Where books get stacked rarely makes a statement, but at Wonder Book, the shelves above and around the bathroom door are stuffed and piled with pulps: Astounding, Galaxy, and countless others, most of them from the 1950s, some of them hiding their half-shredded kin from the ’30s and ’40s. The expensive stuff is aisles away, bagged and secure behind glass, so these are the five-dollar specials, what remains after anthologists spent half a century picking their carcasses clean.

Like many people, I’ve read the best stories culled from these magazines, and I’m familiar with the history of the pulps and their off-kilter editors. When I popped up to Wonder Book, I’d planned only to find some props for Wednesday’s class so my students could see the garish covers, thumb through yellowed pages, and understand how tangible the genre used to be.

But a funny thing happened after I got home: I actually read these magazines and saw how much of the history of science fiction happened between the fiction—in reviews, editorials, letters, and ads. Vivid and downright beguiling, the pulp scene was as alive and interactive as anything on the Internet today.

Here’s L. Sprague de Camp on The Martian Chronicles. This review ran in the February 1951 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, but de Camp sounds for all the world like a smart, impious book-blogger:

Bradbury is an able young writer who will be better yet when he escapes from the influence of Hemingway and Saroyan—or their imitators. From Hemingway he takes the habit of stringing together many short simple sentences and the Providential or impersonal viewpoint, all characters described purely in terms of external action. All right for Hemingway’s Neanderthaloid characters with no minds to explore, but of limited use in a fiction of ideas.

From Saroyan—or perhaps Steinbeck?—he takes a syrupy sentimentality. He writes “mood” stories, of the sort called “human,” populated by “little people” named Mom and Dad and Elma and Grandma. They come from American small towns and build others just like them on Mars. They’re the kind we all know and call “nice—but dull.”

The Web, inscrutable and vast, generates experts who can lecture us, sometimes legitimately, on almost any subject. So behold our monkey ancestors whooping it up around the monolith in Astounding Science Fiction, October 1952:

This is in reply to the query you received concerning how Gödel determined the truth of his “undecidable propositions,” as they are called, in view of the fact that they were unprovable. The question is a good one and is certainly deserving of a reply. When I wrote the article on metamathematics I was much tempted to include a discussion of this very point, but considerations of space limitations ruled otherwise. I shall attempt here to give a partial answer…

Farther afield, hearken to the familiar call of the autodidact in a florid—but to me, totally charming—letter from the April 1946 issue of Famous Fantastic Mysteries:

If you’ll take those limpid orbs off the waste paper basket a moment, I should like to add my voice to the squawks, howls and cauterwauling that beset you.

I was really pleased to find “Phra The Phoenician” so readable. It was a trifle wordy and a bit history-bookish, but beautifully woven together. I’ll bet you a used doughnut that Arnold could quote Shakespeare in reams!

The other story “Heaven Only Knows” was either a filler or an afterthought. “Heaven Only Knows” how it came to be written . . .

[…]

But I did enjoy the mag. as usual. And here’s one fan, Ed., who doesn’t try to hide the covers from the gentry. If people will be allergic to red and yellow, that’s their tough luck. Me, I’m an individualist.

And then we have the June 1952 issue of Other Worlds. In “An Open Letter to Paul Fairman,” editor Raymond A. Palmer bickers with the editor of IF magazine over Palmer’s publication (years earlier, in Amazing Stories magazine) of stories by Richard Shaver, who claimed to have been abducted by an evil subterranean civilization during his stint as a hobo. “Are we plagued by a monstrous detrimental overlordship possessed of titanic science to which we cannot but succumb?” muses Palmer in a five-page, Usenet-class pissing match involving circulation figures, business ethics, and fictional depictions of sex. (Einstein and Jesse James get name-checked, too.)

In an equally rambling five-page editorial, Palmer masks excuses with whimsy and third-person mythologizing:

As a matter of fact, all our friends have been expecting us to do “things.” Never mind what—they expect something “extra” from Ray Palmer. Something maybe nuttier than ever done before; something novel; something which smashes a taboo; something that will cause near homicide…But it almost seemed like one of the characters out of a former “novelty,” the dero, have been trying to prevent him from getting into high gear. Pretty rotten trick, to paralyze a guy so he can’t make his readers happy! Well, one thing after another, and all sorts of troubles—printer trouble, money trouble, health trouble, accident trouble, and so on. Palmer thinks slow. He sits in a coal bin and cogitates. And he comes out looking as if he’d been sitting in a coal bin! But eventually he comes out with an idea. Trouble is, we moved to the country and we burn wood now. No coal bin. No ideas. Carbon is the basis of life; therefore carbon is the basis of ideas—no carbon, no ideas.

Until we found out how to make charcoal!

Elsewhere, Palmer ponders the moral implications of universal military training. (“What has that got to do with science fiction?” he demands. “Nothing! Not a darn thing. Except it’s going to happen in the future. And since when can’t a science fiction editor, writer, or reader even breathe a political word?”)

And here, in the middle of that Other Worlds editorial, is Palmer’s statement on the relationship between editor, writer, and reader:

We’re knocking the walls out! No longer is OW put out in an office in Evanston, the second floor of our company ranchero, a printing plant in Sandusky. It is put out in an arena; an arena bigger than Soldier Field, bigger than Wisconsin, or Illinois, or Ohio. It’s put out right into your own amphitheatre! Every one of you readers is right in the convention hall where you can carry or smash any motion the editor makes. What this means is very simple; we’re going to give you readers a lot bigger voice in OW. We’re coming down out of the editor’s seat and getting right in the middle of things. This editorial, and the Letters section, will become a two-way television set…

The chatty, opinionated prose that ranges from informal to crazed; quirky and passionate readers engaged not only with the editor and writers but also with each other; sober debate broken by hectoring and grand rhetorical flourishes; marginal tweeting about back-issue availability; banner ads for products malevolent and benign—all of these things served as a scaffolding for the Internet to raise a larger and more efficient version of that proto-geek community.

But in 50 years, people will still flip through musty copies of Astounding and understand the pleasure that readers once got from them, while my old Commodore disks will be ciphers to anyone who doesn’t tinker with antiques, and the BBS culture I grew up with will survive only in archived fragments, and even those, like our blogs, can be killed with a click.

The geeky past has a future; I wonder if our geeky present does? We inherited from the pulps a supremely participatory subculture of writing, reading, bickering, joking, scolding, lecturing, and learning, but the world may not remember how all of this felt; you can’t shelve intangibles next to the loo.

Seven years ago, I stepped into a musty workshop in the Balkans and faced the glares of a thousand ancient Serbs. They leaned against walls and rested sideways in racks; a few were upside down. All around, drawn from every corner of the late Yugoslavia, the silent icons were burned, torn, drenched, or devoured by mold. They had been sent to this office for safe keeping—and to await the conservation and restoration that the Serbs may never have the funds or personnel to finish. An eerie sense of patience pervaded the place; in the Balkans, a thousand-year art project is the least reason for despair.

Seven years ago, I stepped into a musty workshop in the Balkans and faced the glares of a thousand ancient Serbs. They leaned against walls and rested sideways in racks; a few were upside down. All around, drawn from every corner of the late Yugoslavia, the silent icons were burned, torn, drenched, or devoured by mold. They had been sent to this office for safe keeping—and to await the conservation and restoration that the Serbs may never have the funds or personnel to finish. An eerie sense of patience pervaded the place; in the Balkans, a thousand-year art project is the least reason for despair. Mirabile visu: Modern technology comes to “Quid Plura”!

Mirabile visu: Modern technology comes to “Quid Plura”! As much as C.F. Cavafy would

As much as C.F. Cavafy would  Life was funny, growing up around characters but not inside a story. I’m not complaining; it was simply true that stories happened in New York or in California, on the shores of

Life was funny, growing up around characters but not inside a story. I’m not complaining; it was simply true that stories happened in New York or in California, on the shores of

Where books get stacked rarely makes a statement, but at

Where books get stacked rarely makes a statement, but at