[This is the first of four blog posts focusing on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s medieval-themed stories. The second post can be found here, the third one is here, and the fourth one is here. If it matters to you, please be aware that these posts about obscure, 80-year-old stories are pock-marked with spoilers.]

Two weeks ago, a footnote jumped out at me like a desperate spark from a dwindling fire. A scholar had ignored what was, to me, a marvel, rushing past it with such haste that he obviously couldn’t dream that I’d want to know more. For eleven years I’ve used this blog to root out medievalism in weird corners of American life—but it had never occurred to me that F. Scott Fitzgerald, of all people, was, for a while, obsessed with writing fiction set in medieval Europe.

Two weeks ago, a footnote jumped out at me like a desperate spark from a dwindling fire. A scholar had ignored what was, to me, a marvel, rushing past it with such haste that he obviously couldn’t dream that I’d want to know more. For eleven years I’ve used this blog to root out medievalism in weird corners of American life—but it had never occurred to me that F. Scott Fitzgerald, of all people, was, for a while, obsessed with writing fiction set in medieval Europe.

But then maybe I’m the only person who didn’t know that in the waning years of his too-short life, Fitzgerald published four medieval-themed short stories in the women’s magazine Redbook in the hope of turning them into his great comeback work: Philippe, Count of Darkness, a novel set in ninth-century France.

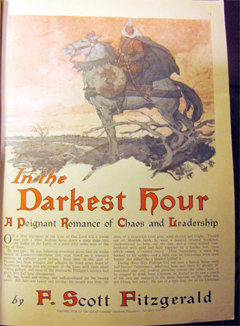

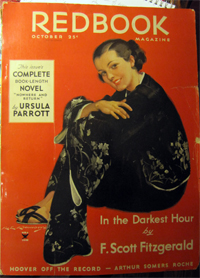

The Philippe stories take effort to locate and patience to read. Fitzgerald’s daughter, I’ve learned, thought they were awful, and only one has been reprinted. I tracked down the necessary back issues of Redbook, half-expecting to find that these stories were the El Dorado of forgotten American medievalism, legends that inspired only folly—but after a few clicks on Ebay it was in my hands: the first story, “In the Darkest Hour,” from the October 1934 issue, where evocative illustrations by Saul Tepper make you long for more from the facing-page ads for soup, sink cleaner, and booze.

What can I tell you about “In the Darkest Hour”? It’s so unlike anything I’ve read by Fitzgerald that if I hadn’t seen his byline on the cover of its crumbling original source, I wouldn’t believe he had written it.

The plot is simple. Spoiler alert: It’s A.D. 872 in the Loire valley, and Philippe, having been whisked away to Andalusia as a child and raised as the stepson of the Muslim vizier, returns to Villefranche as an adult to reclaim his ancestral lands and fulfill his duties as the rightful count. When he finds his homeland ravaged by Vikings and his ignorant subjects scrounging through rubble, he rallies a small band of dubious locals, instructs them in rudimentary horsemanship, and sets them up on mules and donkeys,

as grotesque a caricature of chivalry as could be imagined. Nevertheless, mounted they all were, after a fashion; and Philippe’s idea was a prefiguration of an age already beginning, when mounted men were to take over the shaping of feudal Europe.

Philippe’s pathetic remnant defeats a small band of predatory Norsemen, inspired in part by their count’s promise: He’ll protect his people and keep the peace, in exchange for their good service. Thus by one man, sayeth Fitzgerald, is feudalism invented:

There are epochs when certain things sing in the air, and certain strong courageous men hear them intuitively long before the rest. This was an epoch of disturbance and change; all over Europe men were thinking exactly like Philippe, taking directions from the arrows of history that seemed to float dimly overhead. Each of those men thought himself to be alone, but really each was an instrument of response to a great human need. Each knew that the spirit of man was at low tide; each one felt in himself the necessity of seizing power by force and cunning.

This might be wieldy stuff in the hands of a writer like “Conan” creator Robert E. Howard, who knew that readers clamored for vivid, thrilling tales. They wanted to smell a dank battlefield, feel the rough grip of a spear, sink deep into realms ruled purely by muscle and brawn. The best pulp writers were enwound in their worldviews and knew without doubt what they wanted to say. Fitzgerald isn’t at home here; you can see it in his failing prose. In “certain things sing in the air,” “certain things” should be something more specific, something more evocative of the medieval mind, ideally something that sings. Arrows, though deadly, are too small and fragile to represent the larger forces of history when used so concretely, and saying they only “seemed” to float overhead (rather than speed, whistle, rush, or fly) makes for a week, feeble image. “An instrument of response” evokes nothing specific; a civilizational “low tide” is a cliché. And then after the climactic battle, which ought to leave us feeling like Western civilization is at stake, Fitzgerald observes, lazily: “It was a busy day.”

You’ll search in vain for one sentence in “In the Darkest Hour” that’s worthy of the author of The Great Gatsby. You will, however, find hoard-loads of dialect. People in this story speaks like hard-boiled 1930s gangsters at a poker game in the Old West. Philippe greets the first person he sees with “Howdy! God save you!” and asks “hey, where’s this place at?” When a monk is reluctant to join the fight, Philippe thinks “he’s yellow!” and tells the monk he plans “to protect the jakes.” One local declares: “High time somebody did somethin’ around here. Everything’s rottin’ away.”

I suppose Fitzgerald wants the anachronistic dialect to draw meaningful connections between 1934 and 872, but it’s neither consistent nor emphatic enough to conjure the wisp of a metaphor. In addition to Philippe the Franco-Andalusian expat, we also meet Irish monks, French peasants, and Norsemen, all of whom distrust each other based on differences in appearance and speech. Fitzgerald is hyper-aware of the fact that medieval Europe wasn’t culturally homogeneous, but in a story that otherwise says everything and implies nothing—”[i]t was a desolate countryside, the more so, as there was evidence here and there that it had been once been highly cultivated”—he doesn’t give us a hint as to what he thinks this clash of cultures ought to mean in 1934.

Fitzgerald’s fascination with the Middle Ages surprised me, but maybe it shouldn’t. Raised in a Catholic family, he spent his truncated college years at Princeton, where he read Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West and volumes of early Celtic history on a campus of recently built Gothic halls. By the time he published “In the Darkest Hour” in 1934, American museums were increasing their medieval collections, the cranky medieval-obsessed church architect Ralph Adams Cram had recently been on the cover of Time magazine, and the New York Times was reporting that 370,000 children nationwide were enrolled in youth clubs that preached the virtues of knighthood and chivalry. We think of Fitzgerald as a chronicler of his times, but I think he wanted to understand the foolishness of his era in a much grander scheme, more so than most of us realized.

In The Medievalist Impulse in American Literature: Twain, Adams, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway, Kim Moreland argues that Jay Gatsby is a modern adherent of medieval courtly love. Gatsby navigates a set of rules in the service of adultery and practices a religion of love, “a commitment to the dream, the ideal, the essential, rather than the material, the accidental, the existential…a desire for mystical transcendence.” According to Moreland, Fitzgerald’s own fleur-de-lys fancies eventually withered:

In his novels Fitzgerald explores the cost of a modern allegiance to the courtly model. Yet the validity of the model itself is not seriously called into question. Only in Fitzgerald’s unfinished last novel, The Last Tycoon, does he suggest that the male protagonist perhaps errs in desiring a courtly relationship, that his desire for a courtly lady rather than a modern women might be misbegotten.

In need of new matière, Fitzgerald looked again to the Middle Ages and wrote—what? “In the Darkest Hour” isn’t sufficiently lurid to join the ranks of the best (or even the middling) historical pulp fiction of its era. You’d never know that the author of this flat, prolix story had written sentence after eloquent sentence in Gatsby, a novel that reveres the reader’s powers of inference. Did something other than escapism make a keen observer of his own times look back a thousand years for fresh new things to say?

An editorial note at the end of the story offers a clue: “F. Scott Fitzgerald has written another vivid drama of the dark ages which even more significantly illuminates recent events in Europe and which will appear in an early issue.” Almost nobody delves into medievalism because they wish they had lived in the real Middle Ages; like many before him and many since, Fitzgerald grabs at a medieval metaphor to help him make sense of the here and now. But is the devastated and chaotic Loire valley of “In the Darkest Hour” the Europe of rising fascism and Nazism? A nation wrecked by the Great Depression? An America greatly changed by immigration? There’s little in the story itself that encourages a reader to see anything here but stilted actors in medieval dress.

An editorial note at the end of the story offers a clue: “F. Scott Fitzgerald has written another vivid drama of the dark ages which even more significantly illuminates recent events in Europe and which will appear in an early issue.” Almost nobody delves into medievalism because they wish they had lived in the real Middle Ages; like many before him and many since, Fitzgerald grabs at a medieval metaphor to help him make sense of the here and now. But is the devastated and chaotic Loire valley of “In the Darkest Hour” the Europe of rising fascism and Nazism? A nation wrecked by the Great Depression? An America greatly changed by immigration? There’s little in the story itself that encourages a reader to see anything here but stilted actors in medieval dress.

But then there’s this, a remarkable jotting from Fitzgerald’s notes: “Just as Stendahl’s portrait of a Byronic man made Le Rouge et Noir so couldn’t my portrait of Ernest as Philippe make the real modern man.” Yes, “Ernest,” that Ernest: Philippe, the Spanish-raised French nobleman, is Ernest Hemingway transported to early medieval Europe, where he’ll crack a few skulls and rebuild civilization.

Cheerless after his first modest victory, Philippe holds vigil while weaker men sleep: “Let the others get tired,” he sneers. “I keep the watch.” The closing line of “In the Darkest Hour” sets up Philippe as an indispensable savior: “Embodying in himself alone the future of his race, he walked to and fro in the starry darkness.”

The future of his race. The human race? Christian Europe? Or just the medieval French? As a stand-in for what or for whom? Does it matter that Philippe has blue-blooded authority but is a stranger in his own land? What so ails the world in 1934 that Ernest Hemingway in medieval kit is the only man who can save it?

My questions may be futile. One scholar has called the publication of the Philippe stories by Redbook “an act of charity toward an author in decline.” I don’t doubt he’s right, but in future blog posts I’ll slog through the three later Philippe stories—not to sully the memory of Fitzgerald, whose best work places him safely beyond embarrassment, but to figure out what the heck inspired his obsessive rooting through the rubble of medieval Europe. I want to know what he was looking for, and why he failed so badly to find it.

As the teacher in my household prepares to steer her ninth-graders through tricky literary currents, she’s revisiting

As the teacher in my household prepares to steer her ninth-graders through tricky literary currents, she’s revisiting

Of course—spoiler alert for time-traveling readers from the 1880s—Tom Sawyer plays a huge role in the climax of Huck Finn when he agrees to help free Jim from imprisonment in a shack. Tom and Huck could easily break him out in a moment, but the liberation has to happen on Tom’s convoluted terms. Day after day, Tom draws out Jim’s captivity by insisting on all the elaborate trappings of a swashbuckling adventure novel: a secret tunnel, a coat of arms, snakes and rats, a rope ladder baked in a pie—there’s even talk of sawing off Jim’s leg even though he could free himself from his chain simply by lifting the leg of his bed.

Of course—spoiler alert for time-traveling readers from the 1880s—Tom Sawyer plays a huge role in the climax of Huck Finn when he agrees to help free Jim from imprisonment in a shack. Tom and Huck could easily break him out in a moment, but the liberation has to happen on Tom’s convoluted terms. Day after day, Tom draws out Jim’s captivity by insisting on all the elaborate trappings of a swashbuckling adventure novel: a secret tunnel, a coat of arms, snakes and rats, a rope ladder baked in a pie—there’s even talk of sawing off Jim’s leg even though he could free himself from his chain simply by lifting the leg of his bed.

Last month,

Last month,

When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.”

When Harriet Tubman let an author of sentimental children’s books write her first real biography in 1869, she knew she’d be cast in some curious roles. Abolitionists had already dubbed her “Moses,” and John Brown, who sometimes referred to her with masculine pronouns, had loved to address her as “General.” But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an

But I think there’s more to the Tubman-Joan connection than that. In an  At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to

At last, Joan of Arc was whatever America wanted her to be―except black, except a battle-ready warrior, except an aged ex-conductor on the Underground Railroad. According to

“As Roman civilization received ultimately its cleansing invasion from the hinterland, so American civilization may yet receive its modern counterpart.” So wrote Benton MacKaye in “Outdoor Culture—the Philosophy of Through Trails,” his 1927 address to the New England Trail Conference in Boston (republished in the 1950 collection

“As Roman civilization received ultimately its cleansing invasion from the hinterland, so American civilization may yet receive its modern counterpart.” So wrote Benton MacKaye in “Outdoor Culture—the Philosophy of Through Trails,” his 1927 address to the New England Trail Conference in Boston (republished in the 1950 collection  As a regional planner who worked for the U.S. Forest Service and the Tennessee Valley Authority, MacKaye generated reports that must have read like prose poems to his more practical colleagues. He once argued that hikers, as a small subset of the population, were entitled to mountains of their own in the name of protecting minority rights. During World War II, in a telling example of an expert unable to see beyond his specialty, he advocated that the United States organize its national defense strategy around watersheds. But despite his knack for cryptic pronouncements, MacKaye was always clear about his radical vision.

As a regional planner who worked for the U.S. Forest Service and the Tennessee Valley Authority, MacKaye generated reports that must have read like prose poems to his more practical colleagues. He once argued that hikers, as a small subset of the population, were entitled to mountains of their own in the name of protecting minority rights. During World War II, in a telling example of an expert unable to see beyond his specialty, he advocated that the United States organize its national defense strategy around watersheds. But despite his knack for cryptic pronouncements, MacKaye was always clear about his radical vision.

The daughter of a Congressional Whig, Dahlgren was a Washington socialite and much-consulted etiquette expert. She was widowed twice after marrying prominent men: first an Assistant Secretary of the Interior and then later Admiral John Dahlgren, an innovator in naval ordnance. In 1876, the Widow Dahlgren bought an old inn here on South Mountain, fifty miles outside D.C., and made it her summer home. Although the

The daughter of a Congressional Whig, Dahlgren was a Washington socialite and much-consulted etiquette expert. She was widowed twice after marrying prominent men: first an Assistant Secretary of the Interior and then later Admiral John Dahlgren, an innovator in naval ordnance. In 1876, the Widow Dahlgren bought an old inn here on South Mountain, fifty miles outside D.C., and made it her summer home. Although the

Of mostly local interest, South-Mountain Magic collects Dahlgren’s research into the folkways of her rural neighbors, most of them poor German foresters and mountaineers who weren’t shy about sharing their old-country superstitions. There are stories here about Civil War ghosts on the nearby battlefield, a Native American spirit with its head on fire, jack-o’-lanterns and will-o’-the-wisps, Satanic masses, and even a local wizard whose German spell-book is packed with hexes and cures—which, Dahlgren notes, are always perversions of Christian prayers and rites.

Of mostly local interest, South-Mountain Magic collects Dahlgren’s research into the folkways of her rural neighbors, most of them poor German foresters and mountaineers who weren’t shy about sharing their old-country superstitions. There are stories here about Civil War ghosts on the nearby battlefield, a Native American spirit with its head on fire, jack-o’-lanterns and will-o’-the-wisps, Satanic masses, and even a local wizard whose German spell-book is packed with hexes and cures—which, Dahlgren notes, are always perversions of Christian prayers and rites.

Townsend was once a familiar name in newspaper-reading homes. Although he spent most of the Civil War in New York, Philadelphia, and Europe, he rose from modest beginnings to find renown as a journalist and commentator, first by landing a scoop of an interview with General Philip Sheridan and later by covering Lincoln’s assassination. He published widely under the pen name “Gath,” got rich, and built Gapland, his home here on a

Townsend was once a familiar name in newspaper-reading homes. Although he spent most of the Civil War in New York, Philadelphia, and Europe, he rose from modest beginnings to find renown as a journalist and commentator, first by landing a scoop of an interview with General Philip Sheridan and later by covering Lincoln’s assassination. He published widely under the pen name “Gath,” got rich, and built Gapland, his home here on a

To read too much Townsend in one sitting is to contend with some dreadful poetry and prose: odes to politicians, the treacly story of a

To read too much Townsend in one sitting is to contend with some dreadful poetry and prose: odes to politicians, the treacly story of a