No medievalism this week. Just some links and comments about the humanities, all of them hanging by a common thread.

* * *

From Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K Dick, 1968:

“You androids,” Rick said, “don’t exactly cover for each other in times of stress.”

Garland snapped. “I think you’re right: it would seem we lack a specific talent you humans possess. I believe it’s called empathy.”

* * *

From a Chronicle of Higher Education story about Google Glass:

[Assistant professor of journalism and communication] Mr. Littau said he hoped to see further application of Glass in the classroom, although he could not say for certain what else it could be used for.

“It’s a device made for the liberal arts,” he said. “The whole device is about putting you in the shoes of the wearer to experience the world through their eyes. An auto-ethnography in history could be an interesting thing to experience.”

Only in a visually obsessed age would we believe that literally seeing someone else’s point of view qualifies as an experience. If that’s true, We Are All Cops Cameramen Now.

What’s it like to view a work of art through filters other than your own? How does someone with a trained ear experience classical music? How does someone feel, from his forehead to his gut, when his daughter is born, his candidate loses an election, or his childhood home is torn down? God help liberal-arts faculty who need Google Glass to develop empathy. To make that imaginative leap, just find time for reading and thinking—which are analog, and not recent inventions.

* * *

Here’s a more delightful melding of tech and the humanities: Last week, I found a pocket universe of clever people composing poetry in programming languages.

Experiments with computer-generated poetry aren’t new, but for creative works wrought from the human mind, Perl has apparently been the language of choice. You’ll find poems written about Perl, poetry generators for Perl, Perl poems as April Fool’s jokes, and translations such as “Jabberwocky” rendered in (non-functional) Perl. The go-to text in the field is writer and software tester Sharon Hopkins’ 1992 conference paper and mini-anthology “Camels and Needles: Computer Poetry Meets the Perl Programming Language.”

A Spanish engineer and software developer also put out a call in 2012 for contributors to code {poems}, an anthology of verse in such languages as C++, Python, DOS, Ruby, and HTML. The poems couldn’t just be goofs, though; they had to run or compile. An April 2013 Wired story showcases one of the entries: “Creation?”, a poem in Python by Kenny Brown.

I love this. There’s great creativity here—and a reminder that computers speak only the languages we give them.

* * *

In “Cryptogams and the NSA,” which I’m assuming is not fiction, John Sifton of Human Rights Watch recounts how he was indicted in 2011 after he tweaked the NSA by emailing himself snippets of James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins from a proxy server in Peshawar:

“There are a lot of references to mushrooms and yeast in Joyce,” I said. My attorney touched my arm lightly, but I ran on.

“Look—” I took the book up, “There’s a part late in the book. . . Here, page 613. Halfway down the page.” I pushed it across to Fitzgerald:

A spathe of calyptrous glume involucrumines the perinanthean Amenta: fungoalgaceous muscafilicial graminopalmular planteon; of increasing, livivorous, feelful thinkamalinks; luxuriotiating everywhencewhithersoever among skullhullows and charnelcysts of a weedwastewoldwevild. . .

“See? Fungoalgaceous muscafilicial,” I said. “It’s a portmanteau of different types of cryptogams.”

The stenographer interrupted here, her north Baltimore accent like a knitting needle stuck in my ear. “Are those words in that book?” she asked, “Because – otherwise you’re going to have to spell them.”

She was waved off by one of the US attorneys.

Fitzgerald read the text, or looked at the letters anyway, and then he looked at me again. A kind, blank, innocent look. Unaware of the fear he was instilling in me, not knowing what he was doing, he suddenly twisted the knife.

“And why would someone write like this?”

My silence now. “Why?” I repeated, meekly. I was devastated.

“Just your opinion. A short explanation.” Absolute innocence in asking the question.

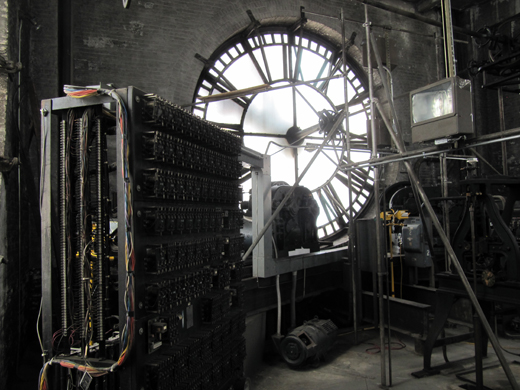

My hands began trembling. One of his assistants looked at the clock.

“I don’t know, sir – honestly I don’t.”

“And why would someone write like this?” Because it’s fun; because it’s artful; because government exists not to perpetuate itself, but to protect these odd, wonderful flourishes of civilization. And because it helps us know who the androids are.

In the 1990s, I met grad students who dreamed of finding the “real” King Arthur; one would-be archaeologist was sure she’d pry Excalibur from the corner of some forgotten Devon field. Back then, most aspiring medievalists only dimly saw that we were riding multiple waves falling neatly into phase, as decades of “historical Arthur” scholarship drew energy from, but also fed, a pop-culture surge of movies, novels, comics, and games. Now that Arthuriana is waning—it’s overdue for a deep, restorative nap—the ghost of Tolkien comes drifting through to provide its “last assay / of pride and prowess”—or, perhaps, to promise its next reawakening.

In the 1990s, I met grad students who dreamed of finding the “real” King Arthur; one would-be archaeologist was sure she’d pry Excalibur from the corner of some forgotten Devon field. Back then, most aspiring medievalists only dimly saw that we were riding multiple waves falling neatly into phase, as decades of “historical Arthur” scholarship drew energy from, but also fed, a pop-culture surge of movies, novels, comics, and games. Now that Arthuriana is waning—it’s overdue for a deep, restorative nap—the ghost of Tolkien comes drifting through to provide its “last assay / of pride and prowess”—or, perhaps, to promise its next reawakening.

This weekend, commerce and revelry engulfed the National Cathedral at

This weekend, commerce and revelry engulfed the National Cathedral at  Unlike Wal-Marts and Targets, cathedrals were each architecturally unique. They were shrines where people hoped and prayed but rarely sated their earthly desires. They were religious institutions whose spiritual offerings didn’t cater to market demands. They were political centers overseen by men who wielded far more local power than any store manager. As distinctive hubs of pilgrimage and tourism, they attracted seekers from

Unlike Wal-Marts and Targets, cathedrals were each architecturally unique. They were shrines where people hoped and prayed but rarely sated their earthly desires. They were religious institutions whose spiritual offerings didn’t cater to market demands. They were political centers overseen by men who wielded far more local power than any store manager. As distinctive hubs of pilgrimage and tourism, they attracted seekers from

If you think there ought to be at least one good poem about the horrific life of the tomato hornworm, then you’re going to like Bruce Taylor. In

If you think there ought to be at least one good poem about the horrific life of the tomato hornworm, then you’re going to like Bruce Taylor. In  I first knew Alan Sullivan through the

I first knew Alan Sullivan through the  Part Virgil, part

Part Virgil, part  For half a century,

For half a century,

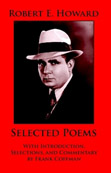

Most fantasy fans know Robert E. Howard as the pulp writer who invented Conan the Barbarian, but he was also a prolific poet. Some of his verse served as epigraphs to his own stories, a few poems appeared in magazines like Weird Tales, and most of it was never published at all. Howard’s Collected Poetry is already out of print—

Most fantasy fans know Robert E. Howard as the pulp writer who invented Conan the Barbarian, but he was also a prolific poet. Some of his verse served as epigraphs to his own stories, a few poems appeared in magazines like Weird Tales, and most of it was never published at all. Howard’s Collected Poetry is already out of print—