[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the “Lloyd Alexander” tag.]

[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the “Lloyd Alexander” tag.]

In 1970, two years after completing his Prydain series, Lloyd Alexander turned to a disenchanted world. Packed with narrow escapes, feline heroics, and political oppression, The Marvelous Misadventures of Sebastian stars a young violinist cast out of a baronial court after offending a pompous count. As Sebastian learns to eke out a living in a fantasy recreation of 18th-century Europe, he has to decide what he really thinks about royalty, tyranny, and revolution. In a world without magic, his opinions, and the actions that proceed from them, have consequences, mitigated only by the cruel mystery of music.

By now, Alexander had established his stock characters: the naive but maturing hero; the tomboyish princess inclined to royal snobbery; and the self-deprecating author stand-in, in this case Quicksilver, who leads a traveling theater troupe. Through Quicksilver, Alexander defends his life’s work by lauding fiction’s simple truth:

“Make-believe and moonshine? Say naught against them! Before the Regent’s bloodhounds snatched away my Harlequin and Columbine, we used to put up a play that did handsomely for us. No more than a nursery tale of a swineherd who killed a dragon and married a princess—with your obedient servant as the dragon. Moonshine? On the face of it, if you will. But I’ll tell you, my lad, there wasn’t a plowboy or kitchenmaid, doddering grandsire or crone of eighty, who didn’t see themselves as the brave swineherd or fair-haired princess. For a little time, at least. And were none the worse for it. Indeed, I’d say they were all the better! Make-believe? There’s more truth at the bottom of it than you’ll find in the Glorietta’s Court Gazette!”

More complicated is Alexander’s approach to music, embodied by a cursed fiddle:

“Lelio called it so,” Quicksilver answered, “and claimed each owner came to grief because of it. As he said, they weren’t the ones who owned the fiddle, but it was the fiddle that owned them; and if they hoped to get music from it, it would cost them dearly. According to Leilo, one poor fellow wasted away the longer he played, as if the fiddle were drinking his life like a glass of wine. Another took leave of his wits altogether, and died a-babbling the fiddle was to blame.”

As it turns out, Leilo the clown suffered for his unfulfilled art:

“I think his heart broke because he knew the fiddle had music in it that even he could never hope to play. He could hear it in his head, but never have it in his fingers. It ate away at him, night and day, until he sickened with brooding over it. And so the fiddle brought him grief, too; and took his life as surely as it had all the others. He told me this as he lay dying in this very wagon, and at the end he begged me to smash the accursed thing, to break it into splinters and burn it.”

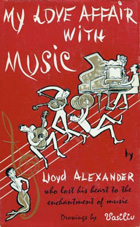

More than ten years after My Love Affair with Music, Alexander found a way to channel his frustrations with the fiddle into fiction, using music to enhance a novel that flirts, ultimately, with political questions.

As in the Prydain books, the villain—here the unscrupulous Regent of Hamelin-Loring—remains offstage until the very end, but his invisibility isn’t about creating an eerie aura of mystery. Instead, the Regent typifies a bad leader who vexes his subjects impersonally, even across vast distances. Alexander sees vestigial virtue in monarchy and suggests that parliamentarianism is the next tricky step in a kingdom’s evolution, but to his mind (and to my great delight), the worst consequence of tyranny is mindless, dehumanizing bureaucracy. When the men of Hamelin-Loring leave their homes to perform mandatory roadwork, the government seizes their land—on the grounds that their farms are now untenanted. “We obey one law—and another punishes us for it!” howls one worker. “Meantime, the Regent lines his pockets all the more.”

The Marvelous Misadventures of Sebastian is a lovely novel, but when you know what follows it, the book feels tentative. In the early 1980s, Alexander would think far more deeply about tyranny, political violence, revolution, and the human tendency to romanticize monarchy in his superb Westmark trilogy—also set in a reimagined 18th-century Europe, and again without a hint of magic. Sebastian deserved its 1971 National Book Award for delivering a rousing story about friendship, maturation, and music, but Alexander needed three more books to disentangle this novel’s political premises—and a decade to ponder the adult implications of fantasy worlds.

[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the

[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the  [Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the

[Here’s the latest in an ongoing series of reviews of all of Lloyd Alexander’s non-Prydain books. To see all posts in this series, click on the