Medievalism is intertwined with the history of the American South. In cities like Richmond and New Orleans, where magazines helped popularize Sir Walter Scott novels and promote chivalric virtues, Gothic revival architecture felt right—but Savannah, where I’m spending Christmas, went its own wonderful way. Here, in a city with countless monuments but surprisingly few statues, you’re more likely to find Georgian, Italian, Federal, and Colonial styles, intermingled but insistently American beneath layers of picturesque moss.

So when you’re the new guy in Savannah, exploring the city’s public squares on foot on Christmas Eve, the search for medievalism seems downright futile…

…but after all these years, I know when to heed the signs. They’re rarely as obvious as this one on Liberty Street.

And so we trudge from moss-bedecked square to moss-bedecked square, wondering as we wander…

Is a lamppost resembling a bishop’s crozier the most medievalism the streets of Savannah can offer?

“No,” says a monstrous sconce on Bay Street. “Look lower, fool!”

Any Jesuit will tell you this totally counts as a gargoyle…

…as does this Seussian goof on the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, though his architect spared him the spitting.

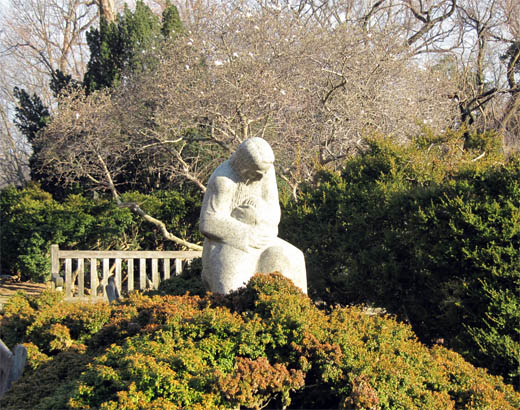

But what’s that in nearby Troup Square?

A neoclassical armillary sphere!? Isn’t there anyone in Savannah who knows what medievalism is all about?

“Sure, Charlie Brown,” says one of six bronze turtles in tiny Santa caps, “I can tell you what medievalism is all about.”

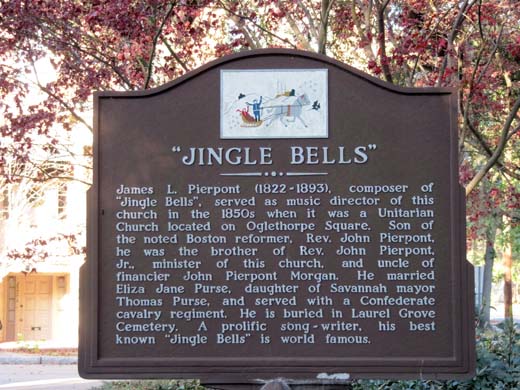

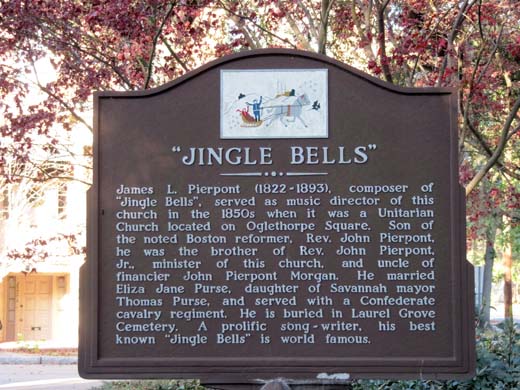

Yep, along this square is the Unitarian church where J.P. Morgan’s uncle served as minister when he published “Jingle Bells.” (Until today, it had never occurred to me that anyone had actually written “Jingle Bells,” or that controversy would attend upon its provenance.)

Amusingly, in the 1850s, Pierpont’s church wasn’t in this square, but a few blocks away. During a low point for Savannah Unitarians, the building was bought by African-American Episcopalians, who industriously rolled it away and set it down here.

So yes, it’s a cosmic treat to stumble around Savannah on Christmas Eve and find a neoclassical Christmas turtle that points you to the relocated church whose minister composed “Jingle Bells”—but what’s medieval-ish about an overplayed ode to the secular sleighing culture of 19th-century New England?

Aha! The composer’s church itself—castellated, Americanized neo-Gothic! Its discovery is hardly a miracle, but the sight of it is fitting end to a charming quest—and a fine way to wish “Quid Plura?” readers a merry (and hopeful, and gargoyle-rich) Christmas.