When I was teaching, and books like Beowulf and The Faerie Queene hove into view, my students gamely kicked around a question: Does America have an epic?

Lonesome Dove. The Godfather. Roots. Each book or movie they floated was a lengthy, multigenerational take on an ethnic or regional experience. Other students brought up Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings, and one of them argued, with rare passion, for Stephen King’s Dark Tower/Gunslinger series. In the end, no one was satisfied. Ours, they sighed, is an epic-less nation.

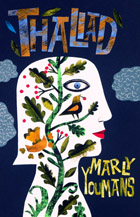

But if we don’t currently have an epic, the people who will live here someday may. That’s the premise of Marly Youmans’ eerie and beautiful Thaliad, a 24-book poem about seven children who survive a fiery apocalypse—and how one of them becomes the founding matriarch of a lakeside tribe in upstate New York.

Recounted 67 years later by Emma, a teenaged librarian who roves the wastes with sword and gun in search of unrescued books, the Thaliad fuses several out-of-vogue elements—formalist verse, narrative poetry, classical epic—to a familiar science-fiction trope. What grows from this grafting is a weird, fresh, magical thing: the story of a new world rooted in the ingenuity and optimism of “one who / Was ordinary as a stone or stem / Until the fire came and called her name.”

Like any classical epic, the Thaliad states its purpose: “to make from these paper leaves / A book to tell and bind the hardest times / That ever were in all of history.” Emma even invokes a muse, but in a nice teen-angst twist, she prays for inspiration from the dream husband she’s sure she’ll never have. “And so I am now married to the quill,” she vows with the melodramatic certainty of youth, recording the origins of her people in a tale that glows with mystical visions, prophetic messengers, and the hard bargain of a divine covenant.

What makes the Thaliad most compelling and real is a certain cheekiness in Marly Youmans’ choice of setting. The children who survive the unexplained holocaust migrate north, as Youmans did, and end up where she lives: Cooperstown, New York, with its nearby Glimmerglass Historic District and Kingfisher Tower, a (yes!) neo-Gothic folly on Otsego Lake. What fantasist hasn’t looked around and wondered what familiar streets and settings might someday become? In that sense, Thaliad recalls Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home, and Youmans is at least as skilled as Le Guin at using mythic elements to solidify and universalize a story, from hints of Beowulf in the raising of funeral mounds to fateful echoes of Ophelia and the Lady of Shalott.

Because epic must be larger than life, Thalia and her fellow children are preternaturally articulate, as is their historian-poet, sometimes in amusing ways. When Emma praises Thalia’s ancestry, we learn that her mother was a doctor, while her father

was unknown, donor of seed,

Impregnator without shape, a formless

Father of the mind who though a mortal

Receives immortal honors from our kind.

By crafting lofty language to describe an immaculate scientific conception, Youmans reminds Thaliad readers that we’re seeing everything in this poem through the eyes of a teenager and the distorting lens of epic—but also that we’re half-blind to the wonders of our own world. Three generations on, Emma doesn’t think much of us:

Then beauty was abolished by the state

And colleges of learning stultified,

Hewing to a single strand of groupthink.

It was a time bewitched, when devils ruled,

When ancient ice fields melted, forests burned,

When sea tossed up its opal glitterings

Of unknown fish and dragons of the deep,

When giant moth and demon rust consumed,

And every day meant more and more to buy.

Some people here and there lived otherwise,

But no one asked them for any wisdom,

And no one looked to their authority,

For none they had, nor were they like to have

The same—no one expects the end of things

To come today, although it must some day,

And so no one expected the great flares…

Fortunately, Youmans doesn’t rest on easy social criticism. Through unsettling depictions of cruelty, negligence, and loss, she argues that despair in times of horror is a choice, not an inevitability. Even as the Thalians struggle to preserve scraps of civilization, the stars over Cooperstown offer another chance for humanity to get things right. Keen to reinvent the constellations, Thalian poets gaze at a sky

Where unfamiliar constellations rule

A dazzling zodiac—the Nine-tailed Cat,

The Throne of Fire, the Fount of Anguishing,

Un-mercy’s Seat. I might go cruelly on,

But I have brooded for too long on fall

And desolation, hidden history

Of world’s end, thing unwritten in the books,

Its causes and its powers scribed on air

And seen out of a corner of the eye

Or not at all. Better to dream and say

That sparking zodiac shows sympathy

For trial and weariness, presenting Hope

In Silver Feathers, Gabriel in Light,

The Mother’s Arms, the Father’s Sailing Boat,

The Seven Triumphant Against the Waste.

To Youmans, whether you like what you see when you look heavenward depends entirely on what you want to see.

Youmans’ hopeful epic has a recent precedent: Frederick Turner’s brilliant science-fiction poem The New World, in which the learned citizens of a 24th-century Ohio republic fend off fanatics in bordering lands. Maybe two poets don’t represent a trend, but a few clever souls have begun to look beyond short, personal lyrics to rediscover the potential of narrative poetry. Christopher Logue’s retelling of Homer is one of the coolest long poems in decades, and Dana Gioia’s most recent book includes a ghost story in syllabic verse.

By writing an epic, Youmans is endorsing a poetic renaissance that has its detractors. Since the 1980s, dyspeptic critics have argued that neoformal poetry is too obsessed with poetry itself (at the expense, they say, of looking out at the world) and that neoformalism “decontextualizes” poetry. Of course, people who point out the same problem with the past century of visual art get dismissed as reactionary cranks, so I’m content to mutter “de gustibus…” and move on. Youmans’ poem is a call to restore old and beautiful forms of literature—that’s what Emma, librarian and historian, literally does when she speaks of the past:

It was the age beyond the ragged time

When all that matters grew disorderly—

When artworks changed, expressive, narcissist,

And then at last became just tedious,

A beetle rattling in a paper cup,

Incessant static loop of nothingness,

When poems sprang and shattered into shards,

And then became as dull as newsprint torn

And rearranged in boredom by a child

Leaning on a window seat in the rain.

Even so, the Thaliad isn’t just literature about literature. By building a plausible world in fiction, Youmans, like any good science-fiction writer, makes us more aware of the weirdness of the real world, where we should look for life in all sorts of seemingly dead things:

We found a sourwood tree that had been killed

By something, but the leaves still drooped in place,

Though every one had faded into brown.

When we came closer, leaves burst into wings—

The tree was green, the death was butterflies,

Alive and pouring like a waterfall

But upside down from us…

Not remotely a formalist novelty, the Thaliad is a remarkable book about surviving a crisis of faith.

Although the Thaliad runs only 102 pages, it’s a rich poem, and I couldn’t find room in this post for half of my notes. Detecting influences ranging from Milton to Cavafy to A.A. Milne, I reacted just as Dale Favier did:

But having finished, I turn at once to the beginning, to read it again, which is of course what one always does with a genuine epic. They begin in the middle of things because they understand that everything is in the middle of things: they’re structured as a wheel, and its first revolution is only to orient ourselves.

If they’re willing to take a chance, fantasy and science-fiction fans and even the “young adult” crowd might all find much to love here. The Thaliad is rare proof that verse need not be difficult or obscure—and that even now, narrative poetry can still leave readers, like Thalian children eyeing strangers in their orchard, “[e]nchanted into stillness by surprise.”

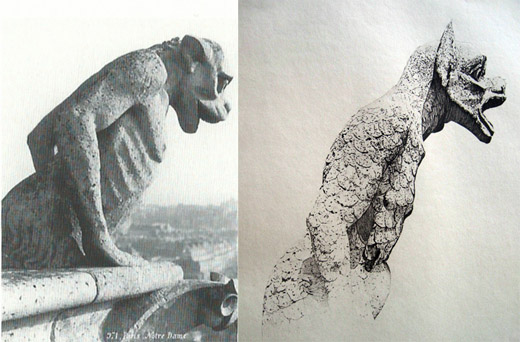

In 2009, after promoting my Charlemagne book and working on projects for other people, I was word-weary and exhausted. To make writing fun again—without worrying about marketability, editors’ impressions, or other people’s needs—I started composing poems inspired by the gargoyles and grotesques that adorn my friendly neighborhood neo-Gothic cathedral.

In 2009, after promoting my Charlemagne book and working on projects for other people, I was word-weary and exhausted. To make writing fun again—without worrying about marketability, editors’ impressions, or other people’s needs—I started composing poems inspired by the gargoyles and grotesques that adorn my friendly neighborhood neo-Gothic cathedral.

If you’re wont to ask, “Where can I see plays that have rarely been staged for 400 years?”, then hie thyself posthaste anon to Staunton, Virginia, where the

If you’re wont to ask, “Where can I see plays that have rarely been staged for 400 years?”, then hie thyself posthaste anon to Staunton, Virginia, where the

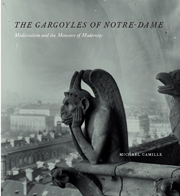

Notre-Dame de Paris! Its gargoyles are iconic—especially the bitter critter on the cover of this book—but even many medievalists aren’t aware that he and 53 of his fellows aren’t medieval at all, but the products of an ambitious 19th-century restoration.

Notre-Dame de Paris! Its gargoyles are iconic—especially the bitter critter on the cover of this book—but even many medievalists aren’t aware that he and 53 of his fellows aren’t medieval at all, but the products of an ambitious 19th-century restoration.